1 . INTRODUCTION

Domestic abuse happens only in intimate, interdependent, long-term relationships- in other words, in families- the last place we would want or expect to find violence.

-Leslie Morgan Steiner

Independence brought many positive changes to Indian society. Sadly, changes in the patriarchal nature of our family structure and the resultant maltreatment of women were not one of these. The females in our society continue to bear the brunt of gendered role and face the wrath of the males in case they fail to fulfill their duties. The presumption of men being superior to women in every aspect of life, based on orthodox views of societies and civilizations which are physically non-existent now, is one of the primary causes of women being treated as subordinate even today, not only by men but also by women at powerful positions in the society. The term domestic violence can mean ill-treatment of both women and men at the hands of their partners and/or their relatives. This ill-treatment may include physical torture, psychological damage, or in many cases, homicide. While we cannot shun the fact that men also get abused by their spouses, there is no doubt that cases of domestic violence inflicted on women are of greater pervasiveness, enormity, and severity as compared to men. Violence against women is so pervasive that no country, society, religion, ethnicity, class, or demographic group can claim to be completely free from it.

The matter of domestic violence, especially in developing countries like India, has mostly been seen from a social and cultural perspective. However, less empirical research focuses on the crucial dimension of domestic violence, i.e., the economic dimension. The economic aspect of this social discrimination is far more complex and much more subtle in its interpretation. Economics is closely related to domestic violence incidences; either it appears as one of the reasons behind violence against women or as an outcome. For example- the rise in unemployment in India from 7.87% to 23.48% between June 2019 and May 2020 and from 6.52% to 11.84% between Jan 2021 and May 2021 (CMIE, 2021) has been claimed to be one of the factors responsible for an increase in the incidences of domestic violence during the lockdown period as husbands inflected their frustration of job loss on their wives, making them victims of domestic violence. It is also conspicuous that in households where the females’ salary is more than the males, the male takes it against his dominating status in the family, consequently resorting to violence to express his dominance over his female counterpart (Alesina et al., 2021). Another instance that underlines the importance of economics behind domestic violence is the fact that explains the implicit reason behind the decision of a woman to stay with her violators. One of the reasons for women to choose an abusive relationship is the less opportunity cost associated with staying perpetrator that otherwise is difficult in existing economic conditions. There is a high probability that a woman will leave her marital house in case of violence if she could manage her economic affairs without any financial aid from her violators. On the other hand, if she perceives that she would not survive on her own, she might choose to stay (Pagliuca et al., 2018).

According to the WHO, globally 1 in 3 women encounter sexual and physical violence in their lifetime, mostly by their intimate partners, and the costs associated therewith are greater than any other form of interpersonal violence (WHO, 2021). While domestic violence is a global problem and has roots in the very nature of family and social structures, the situation is direr in developing countries like India. The economic turbulence triggered by the on-going Covid-19 pandemic is causing intense and extensive impacts on the world over and not just on the economy. The social life in various countries, especially in the developing ones, has been hit severely. Pain, grief, and sorrow are becoming normal than before, and people are learning to live with them. The NFHS (2019-20) data showed a decline in the percentage of married women (18-49 years old) facing domestic violence compared to the previous survey (2015-16) data, from 43.7% to 40% (Rumi, 2020). Many women rights activists were quite sure that the number could increase during the lockdown, and so it did. The National Commission for Women (NCW) reported an exponential rise in the cases of domestic violence during the lockdown period, with a more than twofold rise in cases of gender-based violence, attributed mostly to financial distress and confinement. The commission reported 476 cases of domestic violence online in the first three weeks of lockdown itself (Wallen, 2020), and the data is certainly an underestimate of the actual number as not all women have the opportunity or access to lodge complaints against their perpetrator, especially during the lockdown period when everybody stays at home. The pandemic-induced poverty surge further widens the gender poverty gap pushing more and more women into lives of extreme poverty, making women more dependent upon men for their livelihood and resulting in continuous subjugation of women by men.

The situation in India has been so dire and against women’s welfare that in 2018, a Thomas Reuters Foundation poll named India as the most dangerous place in the world for a woman, even surpassing Syria and Afghanistan, who are constantly at war (Goldsmith et al., 2018). The backward states in India are more prone to domestic violence against women. As per the NFHS-5 survey, conducted in 2019-20, around 40% of the ever-married women of age group 18-49 years in Bihar faced spousal violence, while in more developed states like Kerala the fraction was just around 9.9% (Mantri, 2020; IIPS-ICF, 2021). All this underscores the need to bring this issue to light and deal with it more comprehensively and astutely. The present study attempts to uncover the plausible economic causes and the probable economic consequences of domestic abuse against women in Bihar during the Covid-19 health crisis in 2020-2021.

3 . ECONOMIC FACTORS AND VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN

3.1 Economic Factors Behind Domestic Violence

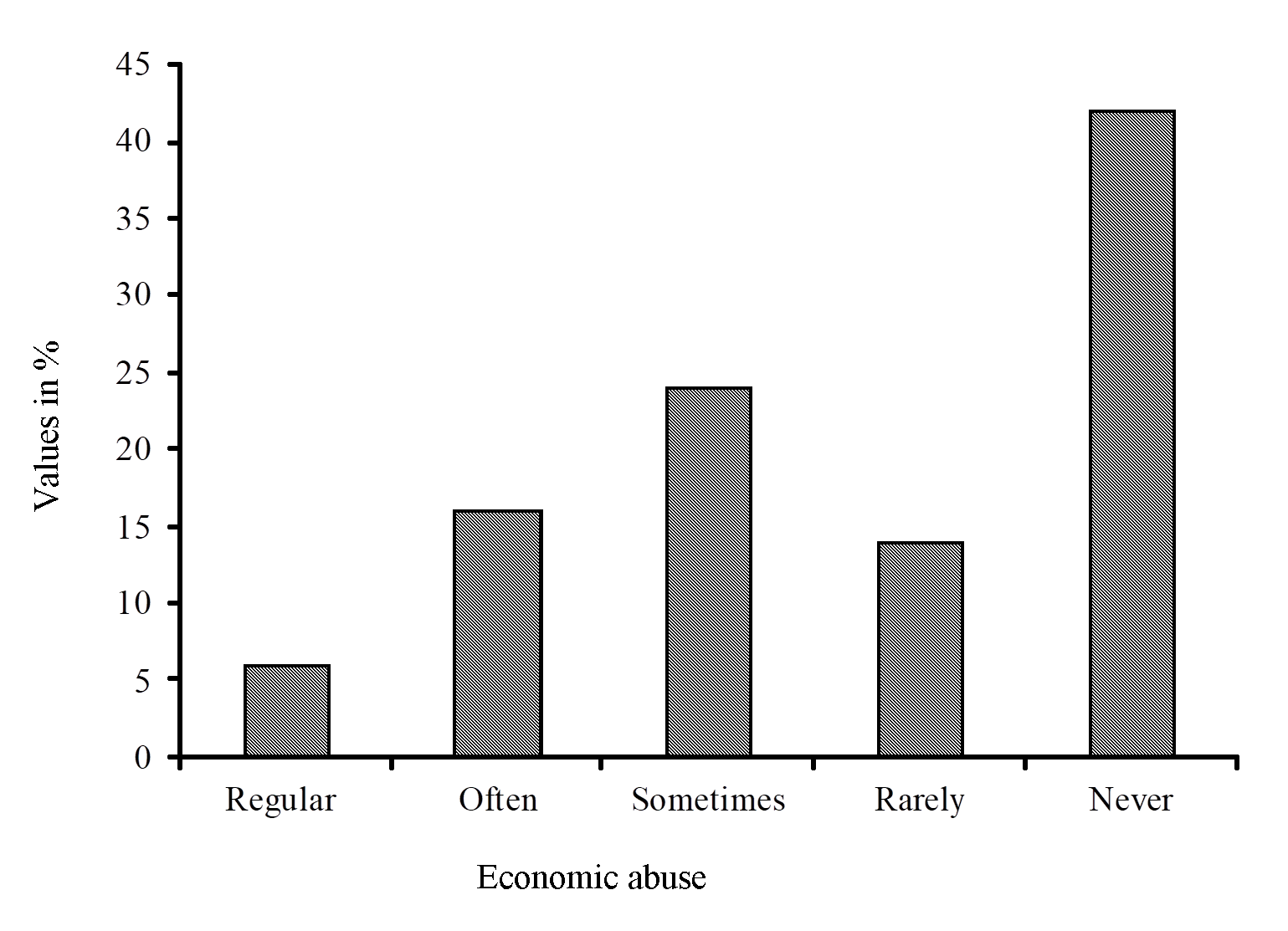

There are different types of domestic violence- physical, sexual, and psychological violence; among these, physical violence is the highest prevailing kind of domestic abuse. A woman belonging to any level of education, nationality, income, religion, age, ethnicity, or class can become a victim of domestic violence (Satija, 2013). Often economic abuse gets overlooked from the discussion regarding domestic violence. However, its prevalence is always notable mostly as the factor responsible for domestic violence. Economic abuse means illegal or unauthorized use of an individual’s money, property, assets, fraudulently acquiring power of attorney, eviction from home, or forcing for dowry and loan. In developing countries, the domestic violence rate is high due to being historically high poverty-stricken countries that promoted women’s economic dependency on the spouses. Further, the low employment opportunities for the economically deprived population coupled with caste and social hierarchy structure culminates financial, social, and psychological stress, resulting in marital conflicts (Gillum, 2019). All the Indian states struggle with the issue of domestic violence against women. Kalokhe et al. (2017) in their study, estimated that around four in every ten women in India had faced some form of domestic violence. It has been identified that, unlike the developed countries, cases of verbal abuse reported are significantly low in India. This is because women in developing countries have become accustomed to verbal abuse and provocation that they ignore the subtle signs of domestic abuse (Dalal and Lindqvist, 2012). The most prominent risk factor that encourages domestic violence is exposure to violence in childhood. Domestic violence has health, psychological and economic impacts on the victims and children who witness violence at home (Usher et al., 2020). Men and women who have witnessed violence in their family during their childhood grow up being more normal towards it and hence are more prone to acts of domestic violence. Moreover, alcohol or drug consumption by the spouse and lower education of women also add up to the condition (Flury et al., 2010; Satija, 2013).

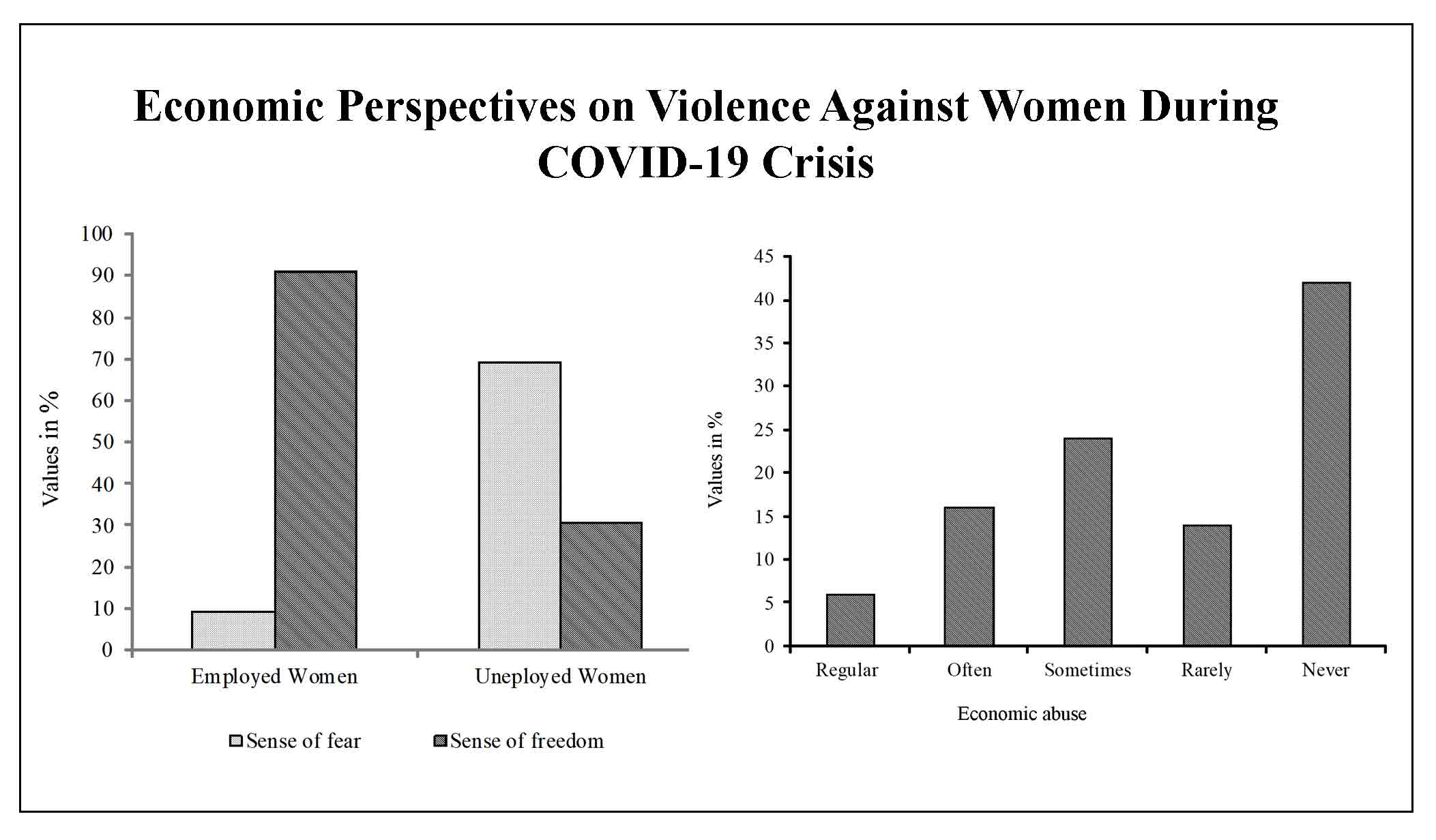

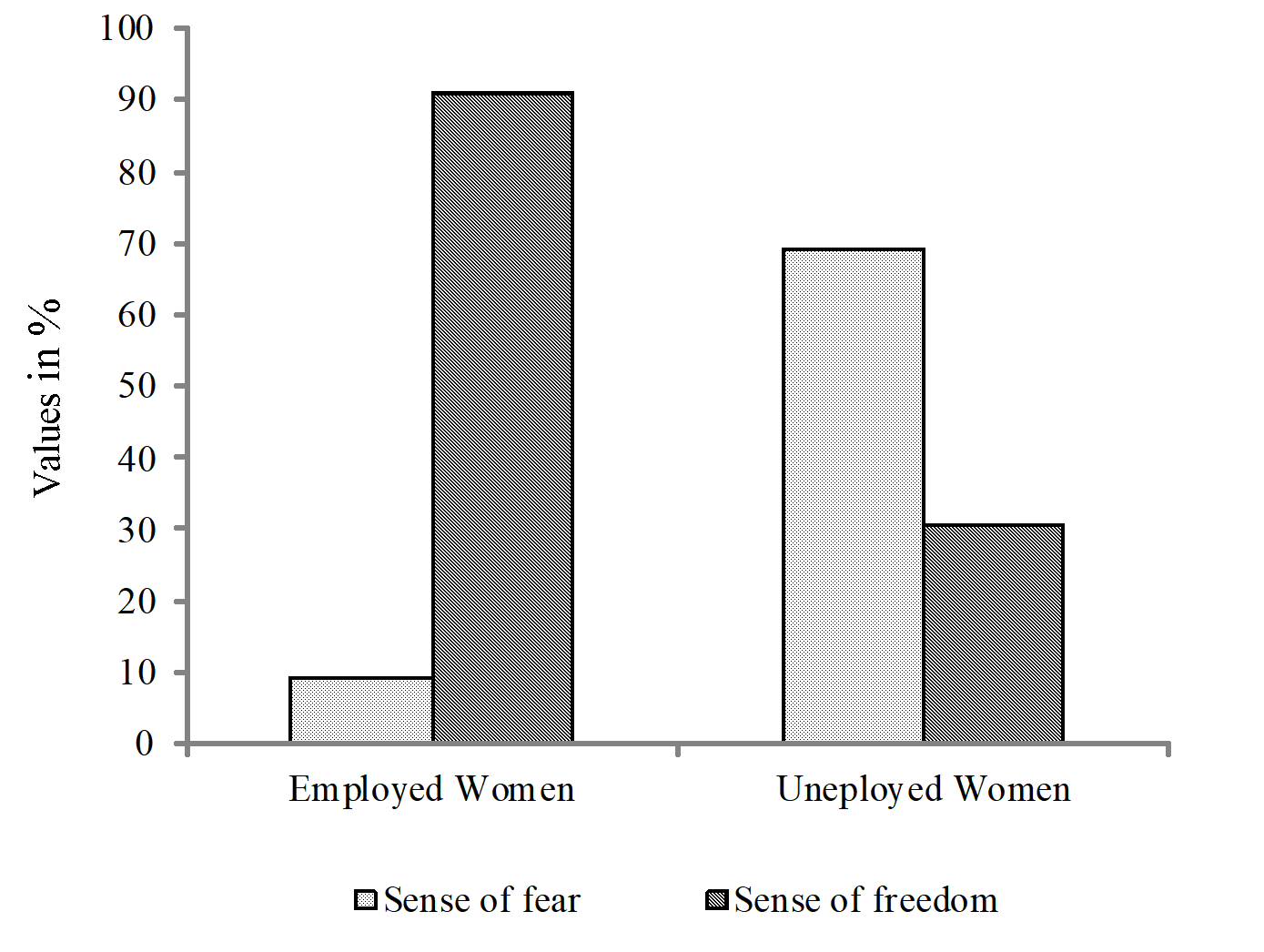

One of the major economic reasons behind increasing domestic violence is the unemployment of both men and women. Over decades, many studies depicted a negative relationship between domestic violence and the unemployment rate of men and a positive relationship between the unemployment rate of women and domestic violence (Mavrikiou et al., 2019). Several scholars argue that men at high risk of job uncertainties choose to conceal their violent disposition from their spouses, apprehending that their partner might leave them in an impoverished situation (Khazan, 2013; Anderberg et al., 2015). In contrast to this argument, Krishnan, et al., (2010) argue that unemployed men are more violent towards their female spouses, and domestic violence decreases when men have employment stability.

Around the globe, patriarchy has a stronghold over the people. For generations, men had used dominating behaviour over their wives to enforce traditional gender hierarchy. Whether a woman is employed or not, she can fall prey to domestic violence. The male backlash theory explains the greater economic opportunity and more wages of women threatens male partners’ dominating nature, leading to emotional and physical abuse to impose their decisions and power over their spouse (Aizer, 2010; Dalal and Lindqvist, 2012; Bolis and Hughes, 2015; Pagliuca et al, 2018; Rocca et al., 2009; Alesina et al., 2021). An India-based study identified that working women belonging to a family with a female head had been twice more exposed to domestic violence compared to those from a male-headed family (Dalal, 2011). Intimate partner violence (IPV) cases are higher among families who encounter greater financial stress (Krishnan, et al., 2010). Ram et al. (2019) revealed that 77.5 % of women between the age group 15 - 49 in the surveyed area suffered domestic violence. The reasons highlighted for such a high percentage are alcohol consumption, controlling the behaviour of the marital family members, and woman’s employment.

On the one hand, women’s employment and control over household resources go against the male hierarchy, consequently rising domestic violence (Krishnan et al., 2010). On the other hand, the unemployed or economically weak women experience domestic violence due to their incapability to support the family financially, struggle with alcoholic husband, and face dominating and violent nature of husband. Furthermore, poverty and paucity of economic resources make the escape from violent relationships more difficult for unemployed women (Krishnan et al., 2010). Matjasko et al. (2013) in their study have raised the concern that the perpetrators use tactics of establishing complete economic control over the victims by malicious interference in their employment prospects, credit control, etc., that restricts the victim from leaving the abusive relationship which makes them even more economically dependent and vulnerable. Furthermore, lack of information regarding economic abuse, fear of consequences of reporting, and children’s responsibility, refrain the victims to complain about the violence. The present need is to address victims’ requirements and build livelihood skills to free women from an abusive relationship without the fear of consequences (Kaur and Garg, 2008).

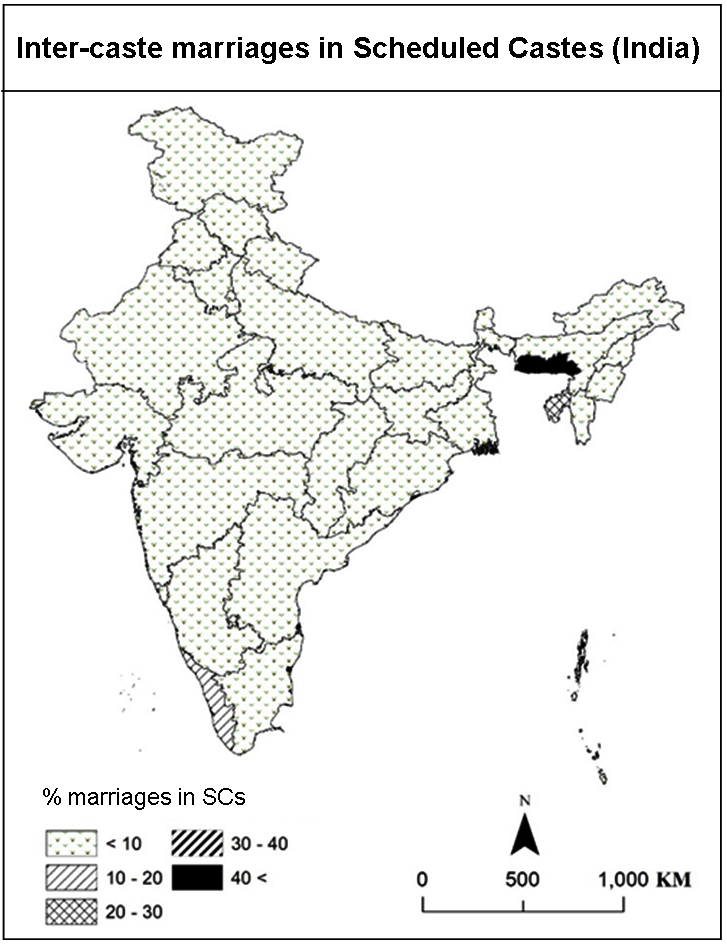

Intersectionality theory also explains the links between the economic empowerment of women and the risk of domestic violence. Various identities such as economic status, ethnicity, social and cultural background, etc. play an integrated role in shaping the link between the economic empowerment of women and the risk of facing domestic violence (Bolis and Hughes, 2015). Class and caste have a vital role to play in domestic violence that builds a strong relationship between physical, verbal, and financial abuse of women and their socio-economic class (Moreira and da Costa, 2020). Working women mostly fall prey to domestic abuse due to alcoholic husbands, traditional hierarchical structure, and economic instability among men of the household (Nagassar et al., 2010). Babu and Kar (2009) pointed out that women belonging to higher socio-economic strata are less prone to domestic violence as they marry into wealthy and educated families. However, such women experience a greater risk of sexual domestic violence (Babu and Kar, 2009). In India, women from the backward caste tend to face more frequent and severe domestic abuse because of their social and economic deprivation. While women from the forward caste experience restrictions on their mobility (Dalal and Lindqvist, 2012). In a caste-based society with a strong establishment of traditional patriarchal family structure, domestic violence cases are usually highest (Satija, 2013). Vander et al. (2015) pointed out that a higher income household has a lower risk of domestic violence, but this does not imply that even hierarchically forward communities will also have a lower risk of domestic violence.

Other than the educational and employment status of the women, age, marital status, and family budget are important risk factors associated with domestic violence (Mavrikiou et al., 2019). Older women of 45 years and above age and widowed encounter domestic violence more than the younger women because of their economic dependency and poor health (Mavrikiou et al., 2019; Babu and Kar, 2009). Also divorced women reported higher cases of domestic violence against their divorced husbands. It also points to the under-reporting by married women due to fear of increased marital conflict. Families having financial difficulties and low budgets also reported a higher risk of domestic violence in comparison to those with a higher budget (Mavrikiou et al., 2019; Babu and Kar, 2009).

The place of residence is also a crucial factor in comprehending domestic violence. Contrary to rural areas, the urban lifestyle is stressful due to the high need for economic resources for livelihood, leading to the greater pervasiveness of domestic violence in urban areas. Further, the occupational structure of women also correlates with incidences of domestic violence against them. More reports are filed against domestic violence by the women engaged in farming and small businesses (Babu and Kar, 2009). Often, it is observed that fewer reports are filed by women belonging to an upper-class family. Renzetti (2009) argues that upper-class women conceal their abusive relationships through their resources, resulting in less reporting of the cases. Economically well-off women can access private health consultants or other better places instead of a shelter home, which the women from lower or middle-income groups lack. Further, affluent families prefer less involvement of authorities due to domestic abuse and conflicts as police records may impact career, community status, and future employability (Holahan, 2019).

Even though dowry is illegal in India, but in practice, the exchange of dowry and gold persists and has a strong relation with domestic violence. The demands of dowry by the marital family prove to be a risk factor for future domestic violence, as the marital family often instigate the perpetration of violence against their daughters-in-law if they are not satisfied with the dowry received (Rocca et al., 2009). Menon (2020) stresses on the relationship between the price of gold at the time of marriage and the act of violence against women. The study presents that in states like Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Punjab, and Delhi, the higher price of gold at the time of marriage means less quantity of it in the dowry. Subsequently, this leads to domestic violence against the bride due to the feeling of discontentment among the marital family, thus pressurizing the bride for more dowry (Rocca et al., 2009). Moreover, monetary aid provided by NGOs and government for the betterment of women is taken away by the spouse or marital family, and sometimes failing to give any sought of financial aid by the victims, make them dependent on the natal family, causing financial stress to the family (Khan, 2015).

3.2 Economic Outcome of Domestic Violence

There is always an economic outcome of domestic violence (Ravindran and Shah, 2020). Several theorists studied tangible and intangible costs related to domestic abuse (Chan and Cho, 2010; Duvvury et al., 2013). Chan and Cho (2010) state that treatment costs for injuries, mental and traumatic treatment costs, property damage, loss of productivity and efficiency, costs of legal services, and victims’ loss of income due to absenteeism are tangible costs, and intangible costs of domestic violence are pain, suffering, and dampened quality of life after domestic abuse. Direct and indirect costs are also associated with domestic abuse, such as loss of wage is a component of productivity loss which gets calculated as the average wage rate multiplied by the average amount of time absent from work (Chan and Cho, 2010; Duvvury et al., 2013).

Domestic violence women victims encounter job insecurities and difficulties in searching for employment (Gillum, 2019). These economic costs are borne by the victims, people around victims, enterprises, and the state. Increased domestic violence at the time of lockdown resulted in decreased work participation, loss of income, and decline in household consumption (Ravindran and Shah, 2020). Domestic violence negatively impacts children’s psychology and education, leading to a reduction in factor productivity in the economy, subsequently affecting the economic growth of the state (Duvvury et al., 2013). Worldwide the cost of violence against women is approx. 2% of the global GDP, which is equivalent to the size of Canada’s economy (UN Women, 2016). Therefore, to mitigate domestic violence cases and associated economic losses borne by society, several domain experts advocate establishing dedicated budgets and enhancing the social support system for domestic violence women victims, as these measures will enhance women’s bargaining power and enable them to negotiate against violent acts (Hsu and Henke, 2021; Wood et al., 2021).

3.3 Domestic Violence at the Time of Crisis

The rise in domestic violence against women in times of crisis indicates a subordinate status of women in our society who still have to bear the brunt of male frustration (Silva et al., 2020). The world financial crisis 2008 and Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 revealed that women are the first to lose their financial stability during any economic crunch. The financial crisis of 2008-09 revealed the relationship between the increasing rate of domestic abuse and rising unemployment, job uncertainties, economic distress. This surge represents the grievous conditions of women in times of health hazards and economic crisis, wherein they have to live in constant fear both inside and outside of their homes (Mondal et al., 2021). The pandemic induced unanticipated economic disruptions, such as unemployment and global downfall in production, loss of income, financial distress, future uncertainties in job prospects, declining wages, lack of resources, female economic dependency on men, and the psychological impact of continuously staying at home for a prolonged period eventually triggered the dominating nature of the husbands within the household (Sharma and Borah, 2020; Usher et. al., 2020; Leslie and Wilson, 2020). Resulting in clashes over decision-making and increased conflict of interests between spouses, ensuing in physical, psychological, or sexual abuse of women at the hands of their partner (Sharma and Borah, 2020; Usher et al., 2020; Leslie and Wilson, 2020; Silva et al., 2020).

The measures taken to curb the virus spread during the pandemic have effects on women that will outlast the pandemic itself, as experienced in previous pandemics and other crises. The UN Women (2020) pointed out the alarming increase in the gender poverty gap due to the pandemic. It is expected that by the end of 2021, there will be 118 poor women over per 100 poor men, and the condition will worsen to 121 poor women over per 100 men by the year 2030. With this increased poverty, women would be more vulnerable to violence and encounter subordination by men at home and workplace. While the economic activity of men rebounds quickly in the post-crisis period, women’s access to employment takes a much longer time to revert to the initial levels. Thus, the pandemic crisis forced women towards more vulnerable conditions by seizing their opportunities for self-empowerment (Roy et al., 2021). Another significant factor that will have a catastrophic impact on women is the mass-scale digitalization of education that restricts the poor and marginalized women from accessing education, pursuing higher studies, and becoming more economically stable. States are gradually withdrawing support from higher education, leading to adverse effects on the education and employment of economically weak women and girls. Subsequently, decreasing their bargaining power in the household in the long run and leading to a spike in domestic violence cases.

Moreover, unemployment, economic stress, job uncertainties among men raises violence against women, as the husband’s dominant status of breadwinner gets threatened in the household (Dahal et al., 2020; Kabeer et al., 2021; Morgan and Boxall, 2020). Economic fallout due to pandemic has hit almost all sectors of the economy severely, ensuing massive jump in the unemployment rate within a short period and uncertainties in husbands’ future job prospects have contributed significantly to the rise in the cases of domestic violence against women as they bear the brunt of their husband’s frustration (Krishnakumar and Verma, 2021). During the 2020 lockdown period, it has been observed that the women who had not experienced violence before faced domestic violence for the first time along with financial distress. Besides, the woman population who had earlier exposure to domestic violence suffered repeated violence during the lockdown (Morgan and Boxall, 2020). In a Spain-based study, data inferred a 23.38% increase in the cases of intimate partner violence within three months of lockdown in Spain (Arenas-Arroyo et al., 2021). Whereas in the USA, from March to May 2020, a 5% increase in domestic violence was noted (Hsu and Henke, 2021). During the pandemic, a large number of women lost their employment and became economically dependent on their partners, leaving no choice other than enduring emotional and physical abuse (Piquero et al., 2021). Unemployment and financial distress decreased the women’s bargaining power within the household, making them more prone to acts of abuse and humiliating conditions.

The rise in domestic violence during lockdown is traceable through exposure reduction theory, according to which violence aggravates if the victim and the violator stay nearby and reduce when they are apart (Hsu and Henke, 2021). Other than economic stress, cohabitation with an abusive partner and alcohol consumption during the lockdown have aggravated the risks of domestic violence (Usher et al., 2020; Leslie and Wilson, 2020; Marques et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2020). The lockdown brought perpetrators and victims near and made social protectors like NGOs and relatives inaccessible (Usher et al., 2020; Morgan and Boxall, 2020; Silva et al., 2020; Mondal et al., 2021; Krishnakumar and Verma, 2021). Moreover, in the pandemic, work from home and economic lockdowns led to a significant surge in the number of complaints and aggravated severity of domestic violence cases against women once the lockdown was over (Sharma and Borah, 2020; Marques et al., 2020).

During Covid-19, the surge in a number of domestic violence is visible across the globe, whether it is developed or developing societies; none are free from this patriarchal setting and gender discrimination. However, cases in India and other less developed countries continue to be more dreadful (Ghoshal, 2020). India already records an alarming rate of domestic abuse against women and available numbers in government records are considered an underestimate of the actuality. Additionally, during 2020 in India, pandemic regions were divided into Red Zone (strict lockdown zone due to immense high Covid-positive cases), Orange Zone (less rigid lockdown zone due to high covid-positive cases), and Green Zone (lesser restriction on movement due to fewer Covid-positive cases). A higher prevalence of domestic violence was visible in the Red Zones of lockdown compared to the Orange and the Green Zones. It was the consequence of stern restrictions in movement in the Red Zone regions (Ravindran and Shah, 2020). Alongside, the backward economic class of people is one of the factors of domestic abuse, as confinement is more burdensome in congested and overcrowded houses in slums (Kabeer et al., 2021).

Pandemic and other crises asymmetrically affect women and girls more because of their traditionally established caregiver role (Ghoshal, 2020). Béland et al. (2020) studied domestic violence in Canada and inferred that neither financial relief provided to reduce the financial stress of the household decrease domestic violence nor work from the home situation for an employed woman affects the risk of domestic violence. However, family stress and violence intensify if a woman is unable to meet her financial obligations (Béland et al., 2020). The growing economic uncertainties and unemployment during the 2020 pandemic have affected the women of backward socioeconomic strata on a wider scale. They became victims of domestic abuse more often than of those belonging to better socioeconomic status and possessing more stable financial conditions (Moreira and da Costa, 2020). Several authors observed that couples who faced higher economic or psychological distress are at a greater risk of domestic abuse than those who were happy and content with their current economic status (Moreira and da Costa, 2020). Ghoshal (2020) draws attention to the need for greater attention towards non-Covid health issues of victims of domestic violence, especially in the Low Resource Settings (LRS), such as India. Most women in developing countries are employed in the informal sector, thus encountering a higher risk of losing their jobs during economic uncertainties and distress. Further, India witnessed a high rate of internal migration of workers during the lockdown. Such migration increased the household burden on women and disproportionately affected them. During the lockdown period, household burden increased, changing lifestyle, and working habits became reasons for several clashes within families. This affected women more as they have significantly less relative social protection than men (UN Women, 2020).

The increased cases of domestic violence during the Covid-19 period have considerably impacted the government’s treasury. To safeguard the victims’ interests, the government has to divert its economic resources that could otherwise be useful in fighting other crises. Loss of productivity due to psychological impacts on the victims is a major economic loss for the states. Thus, domestic abuse has severe consequences on the already ailing economy (Sharma and Borah, 2020). Hence, several experts advocate that states should indulge in vanquishing domestic violence (Leslie and Wilson, 2020). For this purpose, maintaining social contact even in times of national crisis, such as a pandemic, and spreading information about the available support options for the victims is imperative (Usher et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2020). Mondal et al. (2021) urge for spreading awareness among women regarding safe methods of registering complaints against their perpetrators on a similar scale as awareness regarding safety precautions against the Covid-19 virus is being conveyed. Creating easily accessible helplines through mail or messages can prove to be an immediate instrumental tool to mitigate the risks of domestic abuse. Nevertheless, in the long run, awareness drives through popular social media platforms, community collaboration at the grassroots level, and setting up safe shelter homes for the victims are necessary to reduce domestic violence (Ghoshal, 2020).

3.4 Economic Factors and Reduction in Domestic Violence

The household bargaining theory of domestic violence states that women having greater economic opportunities have more bargaining power in the household that lower the risk of domestic violence (Hsu and Henke, 2021; Mathur and Slavov, 2013). Contrary to this argument, Bolis and Hughes (2015) stated that domestic violence against women is even possible after economic empowerment. But economic empowerment increases their bargaining position in the household and creates better opportunities outside the home so that at the time of crisis, women could decide to leave the abusive relationship. Aizer (2010) studied relative changes in the demand for labor in industries dominated by females and compared to those dominated by males in the U.S. The findings represented that a reduction in the wage gap between male and female labors tends to reduce violence against women. A study based on African countries identified that in agriculture-based economies where women could participate more in the production process, develop a more gender status-quo and respect in society, such families are less prone to domestic violence (Alesina et al., 2021). In the same way in India, it has been seen that increasing work participation of poor women in programs like NREGA strengthens their bargaining power which could protect them from violence and reduce incidents of dowry deaths. However, other gender-based crimes such as sexual harassment, kidnapping, etc. increased because of increased women interaction with men in the unsafe work environment, making them victims of workplace violence (Amaral et al., 2015).

Domestic violence adversely affects women’s employment and employability owing to the fact that victims of domestic violence have lower work productivity attributed to the physical and psychological damage from abuse (Renzetti, 2009). Therefore, strengthening economic policies to empower women is of utmost necessity for states to effectively reduce and prevent risks of domestic violence (Hsu and Henke, 2021). The financial and other economic support to the victims of domestic violence may reduce the stress between the married couple resulting in a decline in marital conflicts (Matjasko et al., 2013). Economic stability will provide greater leverage in bargaining for their decisions in the household. A study examined the impact of cash, vouchers, and food transfers targeted to women for reducing intimate partner violence in Ecuador (Hidrobo et al., 2016). It found that transfers either in cash form or in-kind have the potency to lessen the probability of a woman facing physical or sexual violence at her marital home by 6-7%, as it enhances their decision-making power (Hidrobo et al., 2016). However, the conditional cash transfer increases domestic violence. Contrarily, unconditional cash transfers to weaker economic families by the government reduce the incidence of intimate partner violence. Additionally, microfinance programs aiming at providing small loans and vocational training to small business owners reduce the risk of intimate partner violence by reducing economic stress (Tankard and Iyengar, 2018). Matjasko et al., (2013) suggest that providing unemployment benefits and unemployment insurance to all the jobless citizens who are searching for occupation is also an effective way to reduce the risk of intimate partner violence (Matjasko et al., 2013). Alternately, Satija (2013) advocates for encouraging Self Help Groups (SHGs) among poor women to regulate domestic violence against women.

Along with employment, the level of education plays a central role in increasing women’s bargain power. A woman who is economically secure and has some education prefers to report domestic violence (Amaral et al., 2015). It is legitimate to some extent that educated women who have property as their inheritance right or have higher income are more likely to marry a person who is generally not violent by nature (Amaral, 2017; Mathur and Slavov, 2013; Babu and Kar, 2009). Also, economic resources, skills, and education provide self-reliance options to women that allow to exit a violent relationship (Amaral, 2017). The right to property in the natal family significantly improves women’s bargaining power in their marital family and protects them against domestic violence (Babu and Kar, 2009). The inheritance rights impact the household decision-making power of women, approx. 2% of decision-making power is more among the women who have right on their parental property than those who do not acquire the same right (Amaral, 2017). In India, the Hindu Succession Act (HAS) provide women the right to claim their ancestral property which increase women’s status within the family and their bargaining power in the household (Mathur and Slavov, 2013). The Hindu Legal Correspondent (2020) highlights women who have the inheritance right in their paternal property are 17% less likely to be domestic violence victims. A significant 59% decline in the rates of violence against women has been witnessed in the states such as Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu, where the HAS is implemented effectively (Amaral, 2017).

Wood et al. (2021) underline that domestic violence raises concerns around employment, childcare, workplace conditions, and health care access. For curtailing the rising number of domestic violence cases, numerous policy developers, human rights activists, and theorists worldwide have advocated for a wide-scale campaign against domestic violence, provision of economic support to the victims, and strict implementation of laws related to domestic violence (Khan, 2015). Roy et al. (2021) assert on essential requirement for economic aids to the victims of domestic violence as a part of Covid-19 response plans and make social aid, helpline, free post-traumatic medical treatment, and safe house accessible even at the time of lockdown. However, for the long-run solution against domestic violence, an increase in women’s empowerment through employment, higher education, and changes into socially constructed norms of patriarchy and hierarchy are imperative (Dalal, 2011).

,

Prabha Shankar Dwivedi 1

,

Prabha Shankar Dwivedi 1

,

Sheo Rama 1

,

Sheo Rama 1

,

Shreya Sharma 1

,

Shreya Sharma 1