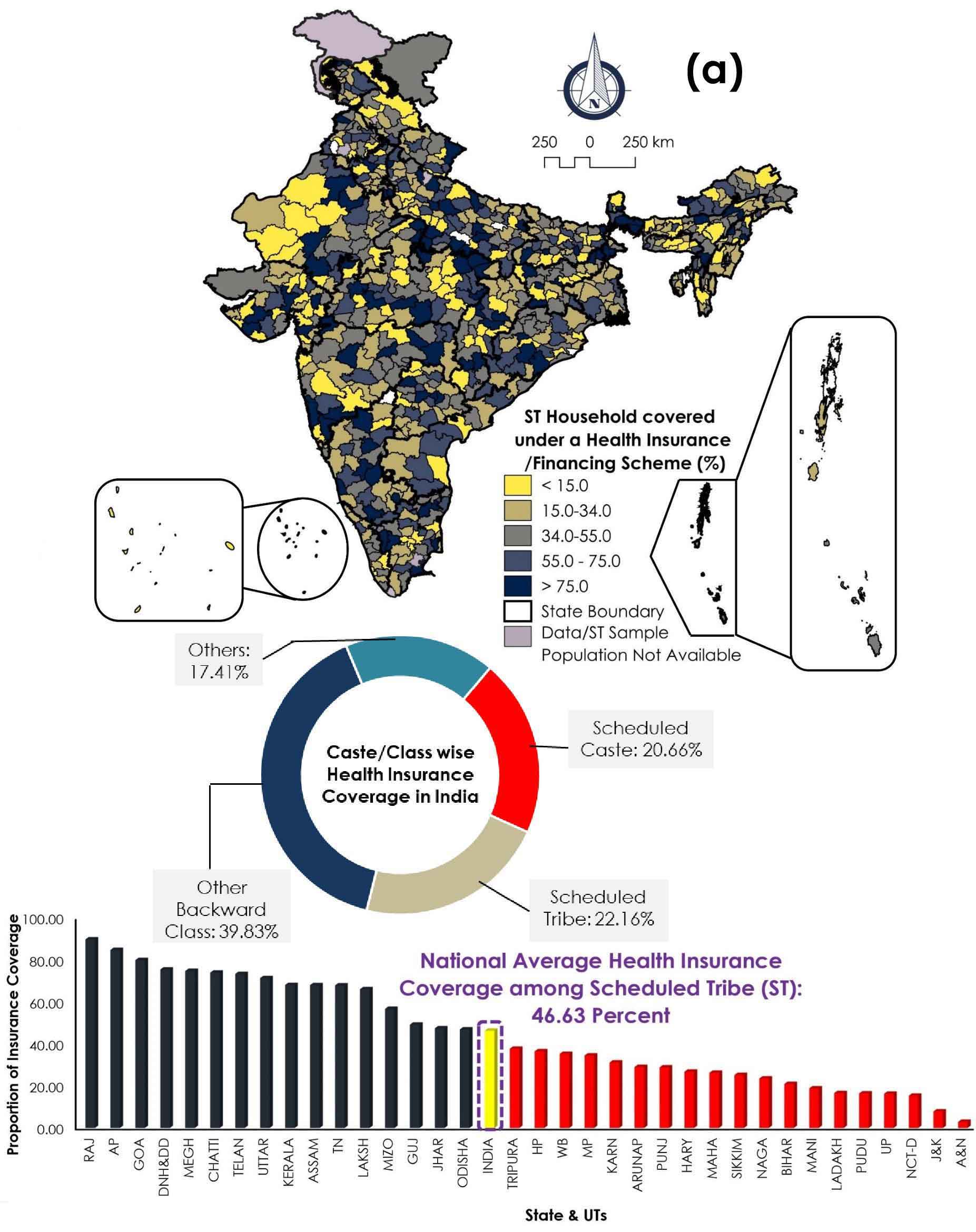

This section presents a comprehensive spatial analysis of health insurance coverage among ST households across India, emphasizing regional disparities, scheme effectiveness, and the interplay with wealth distribution. The geographic variations are mapped across multiple layers, revealing significant north-south and east-west divides in the penetration of insurance schemes.

Spatially, higher coverage clusters are concentrated in the southern, central, and western parts of India, particularly in Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, and parts of Chhattisgarh, where more than 75 percent of ST households are insured. These regions are characterized by relatively robust healthcare systems, improved outreach mechanisms, and a strong presence of State Health Insurance Schemes (SHIS) or other community-based initiatives. In contrast, coverage gaps are notable in Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, and large parts of Northeast India, where coverage among STs often falls below 15 percent. These underperforming areas are marked by developmental backlogs, fragmented health infrastructure, and socio-geographic constraints.

A deeper look at individual health insurance schemes in India reveals a highly fragmented and uneven pattern of coverage for ST households. This ragmented landscape reflects deeper structural issues, including employment patterns, administrative design of schemes, and variations in state-level governance.

The Central Government Health Scheme (CGHS) is primarily meant for central government employees, pensioners and a few selected groups in the formal sector. As a result, its structural design inherently excludes the vast majority of tribal populations, who overwhelmingly work in informal, unorganized sectors such as agriculture, daily wage labor, or forest-based livelihoods. Spatial data show that only a few pockets in states like Punjab, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, and Rajasthan have more than 6.22 percent ST coverage under CGHS. This is not surprising that, tribal workers rarely have formal job contracts, which means they are ineligible for this scheme. Thus, the low outreach of CGHS is not due to administrative failure, but rather due to a misalignment between the scheme’s target population and the socio-economic profile of tribal communities.

Similarly, Employees’ State Insurance Scheme (ESIS) faces similar limitations. Designed to cover employees working in factories and other registered establishments, ESIS also caters mostly to the formal workforce, with benefits such as medical care, sickness benefits, and maternity benefits. Since most ST workers do not fall under formal employment, they are automatically excluded from this scheme as well. Coverage among STs under ESIS remains negligible, with most districts reporting less than 1.46 percent coverage. Again, the root issue here is not implementation inefficiency, but rather structural inaccessibility due to eligibility criteria. This raises important policy questions about the need to design insurance frameworks that reflect the actual working conditions of India’s most marginalized. Community Health Insurance Programs (CHIP) represent a more inclusive and localized model of health financing, often managed by non-governmental organizations (NGOs), cooperatives, or state-sponsored initiatives. These programs are sometimes tailored specifically for low-income and socially excluded groups, including tribes. Spatial analysis shows slightly better coverage under CHIP in parts of Rajasthan and the Northeast, where community-based organizations have successfully mobilized tribal participation. In some districts, CHIP coverage for STs exceeds 4.35 percent still low, but relatively higher compared to CGHS or ESIS. The advantage of CHIP lies in its bottom-up approach, relying on community trust, social solidarity, and local health workers to build participation. However, CHIP remains localized and underfunded, with limited scalability due to funding constraints, lack of integration with state systems, and poor monitoring mechanisms.

In contrast to the central schemes, State Health Insurance Schemes (SHIS) have shown the greatest success in reaching tribal households. These schemes are often custom-designed by state governments to meet local needs, sometimes using their own funds or leveraging central support. States like Rajasthan, Andhra Pradesh, and Telangana have achieved ST coverage levels exceeding 76 percent in several districts, largely due to strong political will, institutional capacity, effective public-private partnerships, and on-the-ground outreach mechanisms. In some northeastern states as well, certain districts exhibit high SHIS coverage. However, others, such as Assam, Manipur, Nagaland, and Tripura continue to lag due to administrative bottlenecks, lower resource allocation, or geographical challenges. Importantly, the success of SHIS programs demonstrates that decentralized, state-led efforts can effectively penetrate remote and marginalized areas, provided there is sustained investment and local adaptability.

Privately purchased commercial health insurance typically offered by for-profit insurance companies is almost non-existent among ST populations. Only a few relatively better-off districts in Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, and Sikkim show marginally higher uptake (still less than 12 percent). For most tribal households, private insurance remains unaffordable, difficult to understand, and disconnected from their lived realities. These schemes often involve high premiums, complicated paperwork, and urban-centric hospital networks all of which alienate the average tribal consumer. Moreover, there is a lack of financial literacy, digital access, and insurance awareness in tribal belts, further preventing engagement with the commercial insurance market.

Interestingly, some southern states such as Tamil Nadu and parts of Kerala, along with isolated pockets in the Northeast, show aggregated insurance coverage through a mix of SHIS, CHIP, and legacy schemes. These areas benefiting from more developed public health infrastructure, stronger primary care systems, and institutional continuity demonstrate relatively higher coverage among ST households.

3.2 Spatial Inequality Pattern Identifications: EBS, Univariate LISA and Getis-Ord Gi*

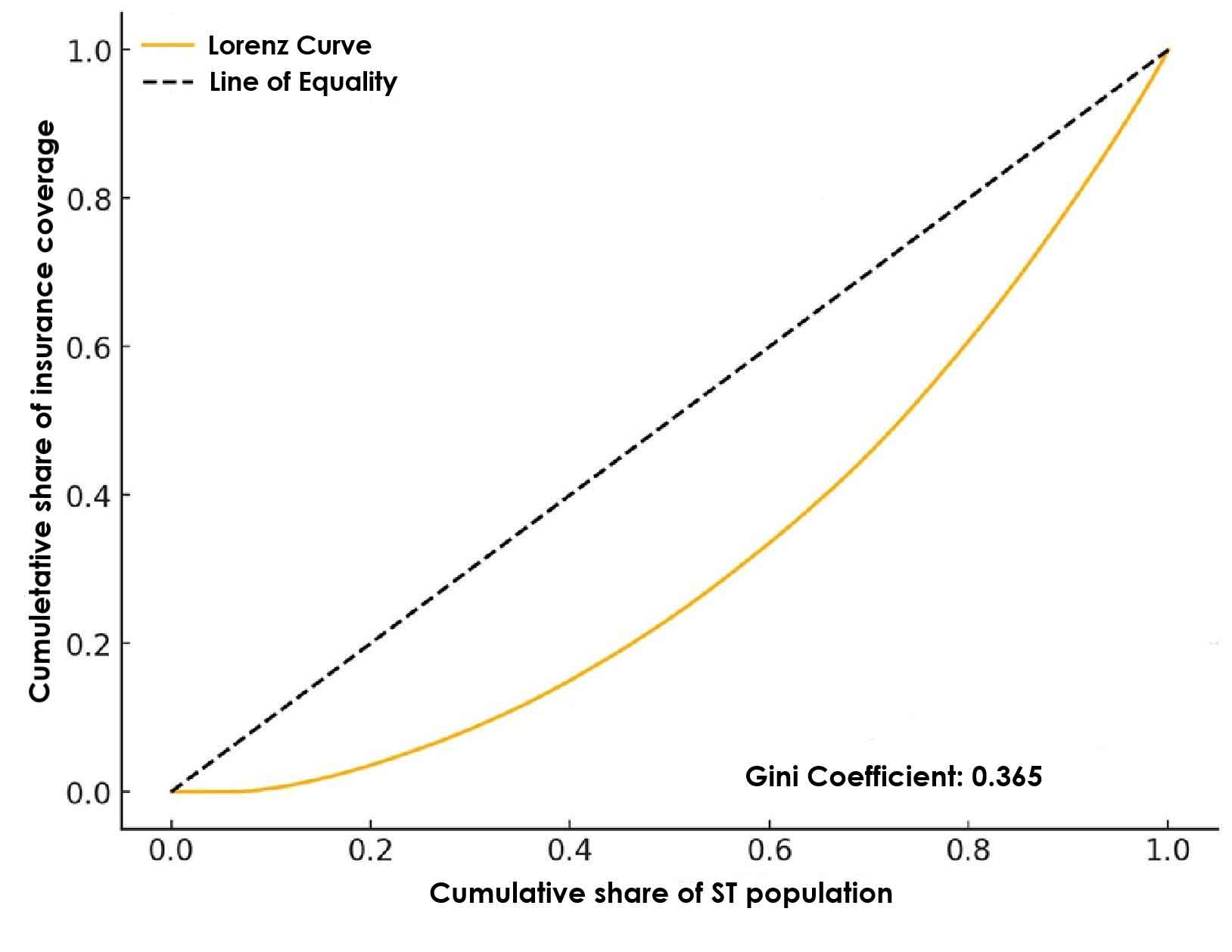

Figure 5 offers a detailed spatial analysis of health insurance coverage among Scheduled Tribe (ST) households across India present a clearer and more reliable picture of geographic disparities. The Figure 5 focusing on the spatial distribution and the application of Empirical Bayes Smoothing (EBS) to correct for statistical noise in areas with small populations or low counts. EBS is critical in ensuring that rates are more stable and less biased by small population sizes, which can lead to exaggerated or misleading high/low rates. EBS helps stabilize these values by borrowing strength from neighboring areas and adjusting extreme or unreliable figures. This results in a smoothed map, where patterns are clearer, and the influence of random chance is reduced. In simpler terms, it ensures that small or rural districts are not unfairly represented as outliers just because of their size. This method allows for a more reliable spatial interpretation of health insurance coverage, especially in areas with smaller populations or extreme values, smoothing out random fluctuations.

The application of Empirical Bayes Smoothing (Figure 5a) serves as a foundational step by adjusting for statistical instability in districts with small populations or sparse coverage data. This method minimizes the risk of overestimating or underestimating coverage in low-count areas, thereby ensuring that the observed patterns reflect systemic realities rather than random variation. The smoothed data reveals a clear north-south and east-west divide, with southern and western states, notably Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Gujarat exhibiting consistently high levels of insurance coverage among ST households. These regions are characterized by better healthcare infrastructure, higher health awareness, and the effective deployment of State Health Insurance Schemes (SHIS).

In stark contrast, the northern, northeastern, and central regions, particularly Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, and parts of the Northeast register lower smoothed coverage rates, suggesting systemic barriers such as infrastructural deficits, weak governance, limited institutional outreach, and socio-economic exclusion. The adjusted figures confirm that these are not statistical outliers but structurally disadvantaged zones, requiring sustained public policy attention.

Building on this smoothed baseline, Local Moran’s I was employed as a spatial autocorrelation statistic to detect localized patterns of clustering and outliers. Unlike global measures of spatial autocorrelation, which summarize spatial dependence across the entire study area, Local Moran’s I enables the identification of local-level spatial dependencies, offering nuanced insights into how insurance coverage is distributed relative to neighboring districts.

The application of Local Moran’s I to the EBS data revealed a statistically significant spatial structure in the distribution of ST health insurance coverage. Specifically, four categories of spatial association were identified: High-High (HH) clusters, Low-Low (LL) clusters, High-Low (HL) outliers, and Low-High (LH) outliers. These spatial patterns illustrate how certain areas exhibit positive spatial autocorrelation, districts with similar levels of coverage tend to cluster together, while others demonstrate negative autocorrelation, where districts differ sharply from their neighbors. The combined scenario of Figures 5a, 5b, and 5c reveals pronounced regional disparities in insurance coverage for ST households. Broadly speaking, southern and western India emerge as hotspots of high and consistent coverage, while northern, northeastern, and central India display cold spots zones of persistent exclusion and under coverage.

The HH clusters represent regions where districts with high insurance coverage are surrounded by other similarly high-performing districts. These clusters were predominantly located in southern and western India, notably in Kerala, Tamil Nadu, parts of Rajasthan, and Gujarat (Figure 5b). The spatial concentration of high-coverage districts in these states reflects not only stronger health infrastructure and administrative capacity but also the successful implementation of SHIS. The clustering effect suggests that health policy interventions in these regions have likely benefited from regional policy diffusion, where best practices and institutional capacities spill over into neighboring districts, creating reinforcing zones of success.

Conversely, LL clusters were found in several northern, central, and eastern states, especially in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, and parts of Maharashtra (Figure 5c). In these districts, low insurance coverage is surrounded by similarly underperforming areas, indicating the presence of spatially entrenched disadvantages. These LL clusters are emblematic of broader structural issues, such as weak state capacity, under-resourced health systems, limited community outreach, and socio-economic marginalization of tribal populations that transcend district boundaries. The spatial persistence of these low-performing areas calls for coordinated, multi-district interventions that go beyond isolated programs and address regional governance failures and infrastructural deficits.

In addition to these core clusters, outlier patterns also emerged, with HL and LH associations marking spatial discontinuities. HL outliers indicate districts with high coverage surrounded by low-performing neighbors, while LH outliers suggest the opposite. These outliers are analytically significant because they may represent localized innovations or implementation anomalies. For instance, a district showing HL association might be benefiting from a successful local insurance pilot, NGO intervention, or a particularly efficient health administration. Conversely, LH districts may be constrained by localized barriers, such as poor terrain, political neglect, or community resistance despite being surrounded by otherwise better-performing districts. In essence, these spatial diagnostics make a compelling case for moving beyond national averages and one-size-fits-all policies. Recognizing these outliers offers strategic entry points for policy learning and localized troubleshooting. As India advances toward universal health coverage, such geographically informed approaches are essential to ensuring equity, inclusion, and structural justice for historically marginalized communities.

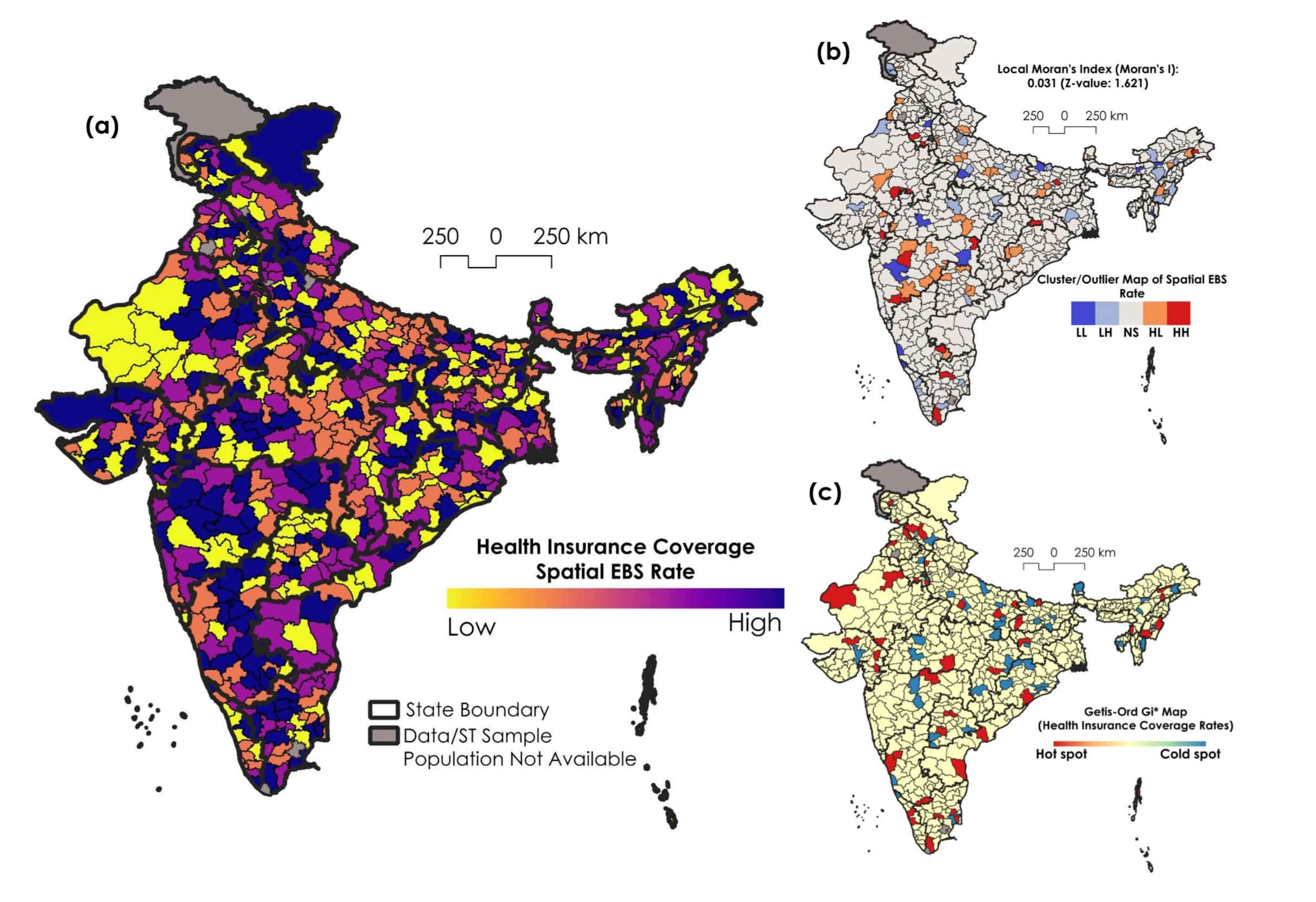

3.3 Regional Disparities in Wealth and Insurance Coverage

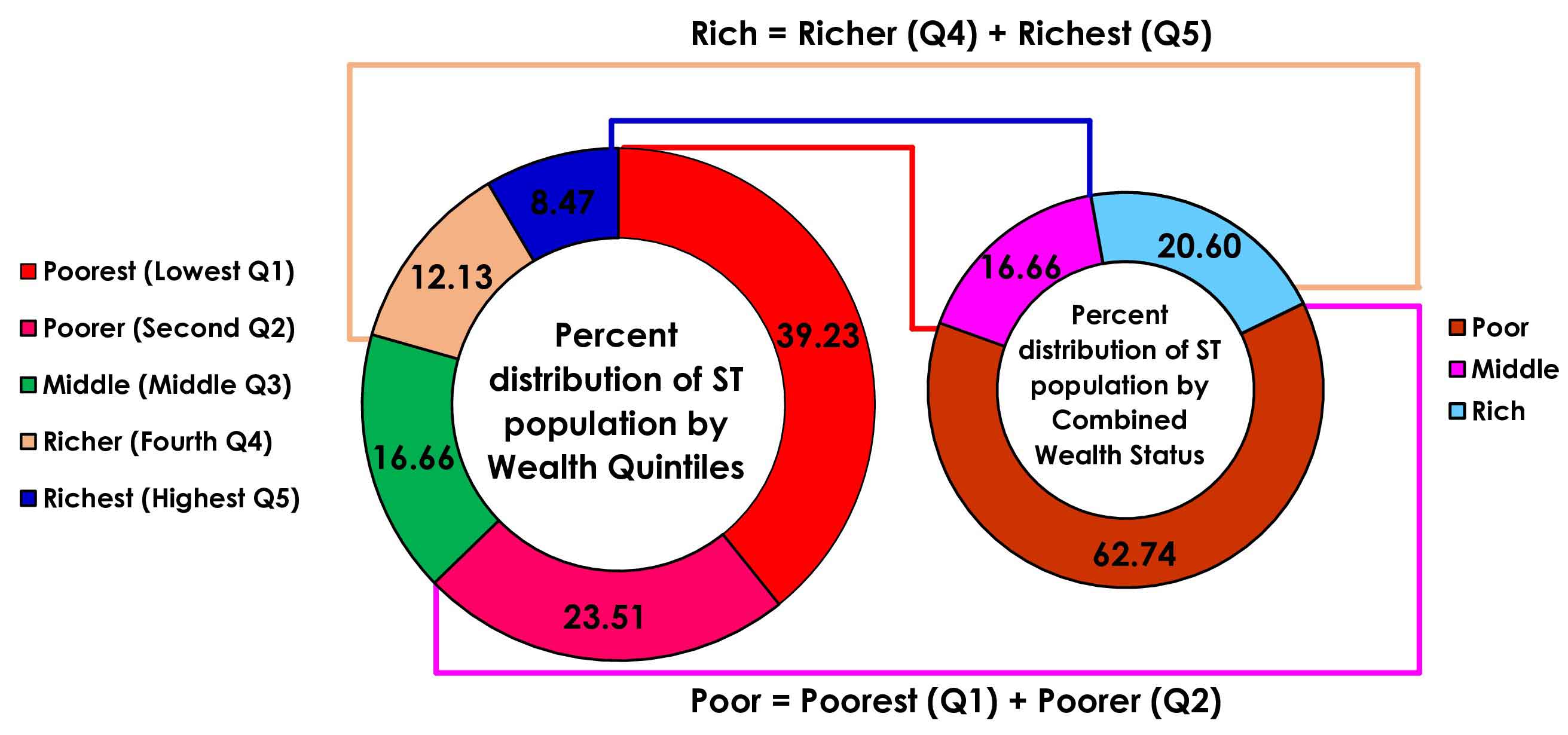

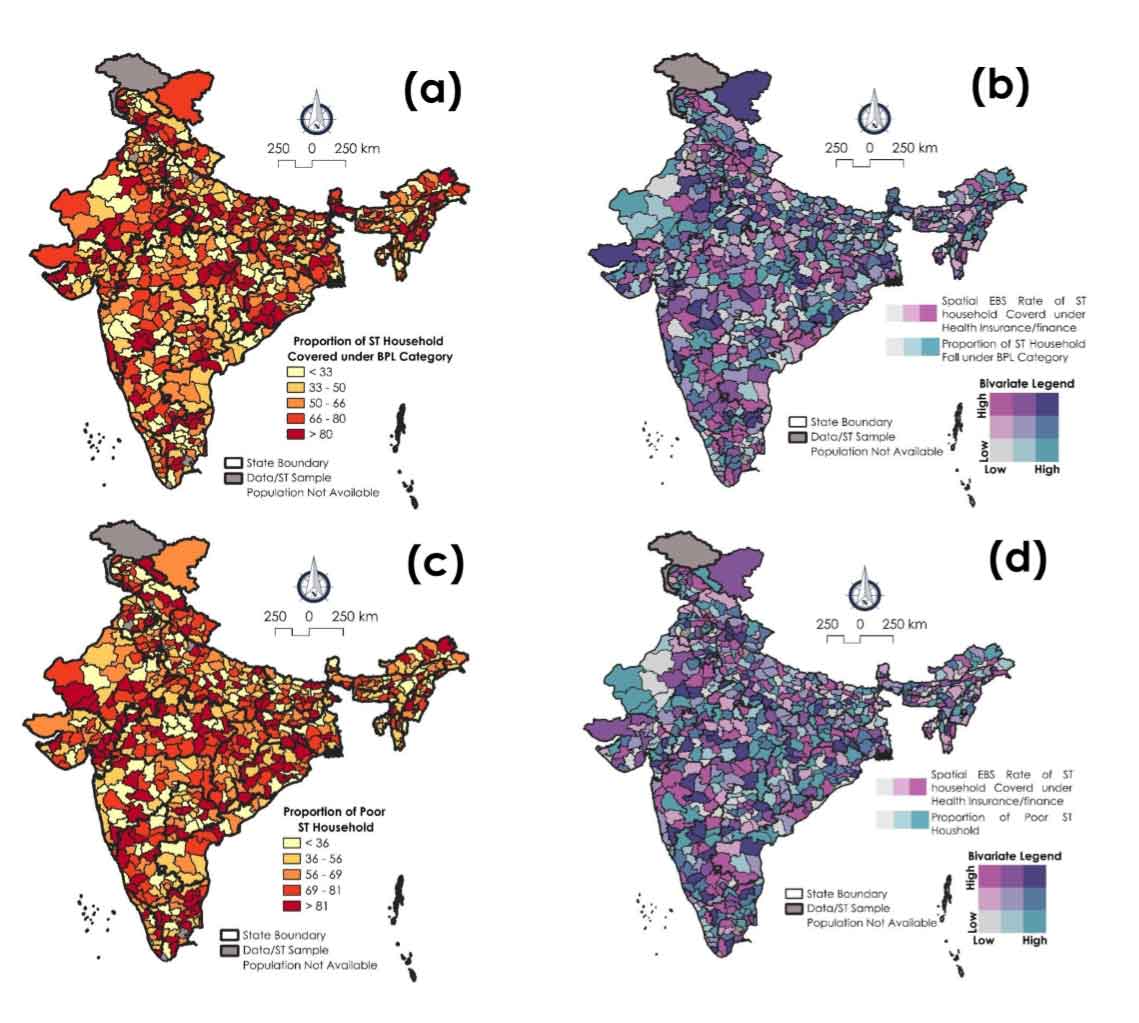

The maps presented in Figure 6(a-d) provide a detailed spatial perspective on the distribution of economic status among Scheduled Tribe (ST) households in India and its interrelationship with health insurance coverage at the district level. Through both univariate and bivariate spatial visualizations, these maps facilitate unpack the geographic inequality in wealth and healthcare access among tribal populations two fundamental dimensions of social security.

Figure 6a illustrates the spatial distribution of rich ST households, those situated in the upper economic tier among tribal communities. The map shows a pronounced spatial concentration of these households in southern and western India, especially in states such as Karnataka, Maharashtra, and parts of Gujarat, where over 36.1 percent of ST households fall under the 'rich' category. These areas tend to have better infrastructure, more diversified livelihoods, greater exposure to urban economies, and in many cases, stronger government program implementation. In contrast, northern and eastern states, including Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, and West Bengal, have very low proportions of rich ST households, often below 5.8 percent. These patterns reflect historic and systemic disadvantages, including landlessness, lower educational attainment, and weaker integration into regional markets.

Importantly, this wealth distribution is not random. As shown in Figure 6b, when overlaid with health insurance coverage, a clear positive spatial correlation emerges in several regions. In districts where the proportion of rich ST households is high, particularly in the south and west health insurance coverage rates are also significantly higher. This co-occurrence of wealth and insurance coverage suggests a reinforcing relationship: economically better-off tribal households are more likely to enroll in or benefit from insurance schemes, possibly due to greater awareness, better access to administrative networks, or the ability to meet formal documentation requirements.

Conversely, in districts across the north and east, where tribal communities are predominantly poorer, both wealth and health insurance coverage remain low. This dual deficit, low economic capital and inadequate health security reflects a vicious cycle of exclusion, wherein lack of financial means directly limits access to essential health protections. These findings underscore a critical insight: wealth inequalities among STs directly translate into health protection inequalities, perpetuating socio-economic vulnerability over generations.

While rich households represent a narrower economic elite, the moderate-wealth or middle-income ST households form a much larger segment and offer insight into emerging socioeconomic mobility. Figure 6c maps the distribution of these households, revealing a broader but more uneven pattern. Higher proportions of middle-wealth ST households are concentrated in the central Indian belt, notably in Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and selected districts of southern and northeastern India. These areas typically represent transitional zones, where tribal communities have gained some economic traction through agriculture, public sector employment, or state-level welfare schemes, but remain vulnerable to shocks. Figure 6d explores the bivariate spatial association between the proportion of middle-wealth ST households and health insurance coverage. The relationship here is positive, but weaker than that observed with the richer ST group. Districts with higher proportions of middle-income households, especially in the central and southern regions do tend to show better insurance coverage, yet the improvement is less consistent and often influenced by state-specific policies and local implementation efficiency. This suggests that while economic upliftment contributes to improve insurance access, it may not be sufficient on its own without targeted enrollment drives and administrative support.

Interestingly, several middle-wealth clusters do not exhibit proportionally high insurance coverage, indicating gaps in policy outreach or information dissemination. For instance, a household with modest resources may still fail to enroll in insurance schemes due to lack of awareness, language barriers, or difficulties in navigating complex administrative procedures. Therefore, the relationship between moderate wealth and insurance coverage is more sensitive to non-economic factors, including social capital and governance quality. These patterns underscore the multidimensional nature of vulnerability among tribal households, where economic status, geography, and healthcare access intersect. Importantly, while improving wealth conditions is key, it is not sufficient on its own.

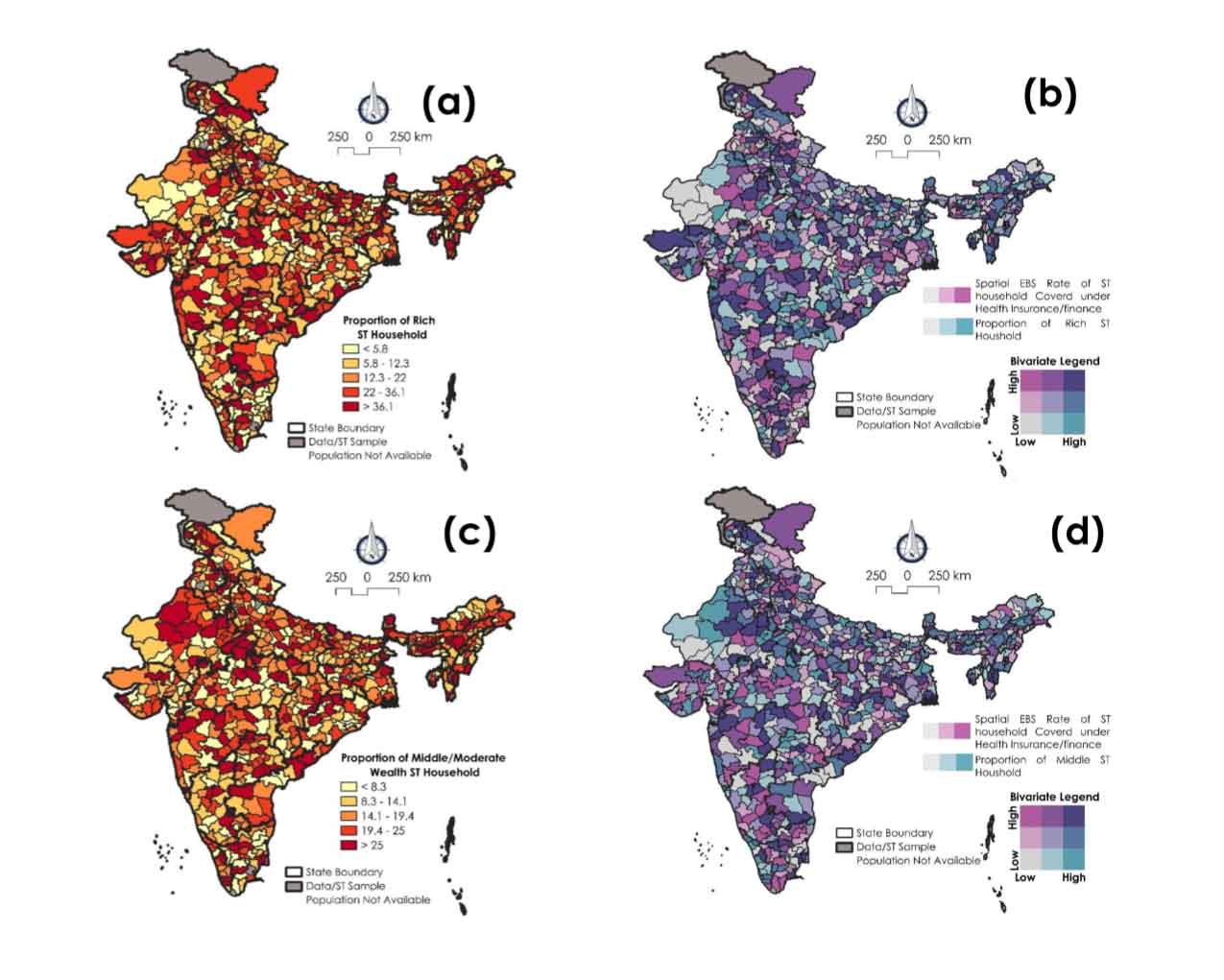

The maps in Figure 7 (a-d) deepen our understanding of the intersection between economic vulnerability and healthcare access among Scheduled Tribe households in India. These visualizations focus specifically on two markers of deprivation: households falling under the BPL classification and those designated as ‘poor’ based on wealth quintile data. When these economic indicators are analyzed in tandem with health insurance coverage, they reveal stark regional inequalities and structural disadvantages that disproportionately affect tribal communities in specific parts of the country.

Figure 7a presents the district-level distribution of ST households categorized as BPL a designation commonly used in policy targeting to identify socio-economically disadvantaged groups. A distinct north-east concentration is observed: districts in Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha, and West Bengal show very high proportions of ST households under BPL, often exceeding 80 percent. These regions are historically underserved and exhibit persistent deprivation across multiple social indicators, including land ownership, literacy, and employment.

By contrast, southern and western states such as Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, and parts of Maharashtra display a lower proportion of BPL-classified ST households, generally below 33 percent. This reflects comparatively stronger socio-economic conditions, better access to welfare services, and improved livelihood diversification in these regions. When the BPL data is paired with health insurance coverage in Figure 7b, a clear and inverse spatial pattern emerges. In districts where BPL proportions are highest, especially in northern and eastern India, health insurance coverage tends to be lowest. This indicates a negative spatial association, suggesting that the very regions with the highest economic vulnerability are also the most underserved in terms of health protection. This finding challenges the intended targeting mechanisms of public health schemes, many of which are specifically designed to prioritize BPL populations.

Conversely, in some southern and western districts the share of BPL households is lower, yet health insurance coverage is relatively high. This geographical misalignment between economic need and healthcare protection highlights a critical policy gap. While wealthier or less vulnerable regions are achieving better enrollment and insurance uptake, the most economically distressed areas, which should, in theory, be receiving the most support are being left behind, possibly due to administrative bottlenecks, lack of awareness, or geographic inaccessibility.

Complementing the BPL analysis, Figures 7c and 7d examine the proportion of ‘poor’ ST households as classified by asset-based wealth indices, offering a broader and more multidimensional view of poverty. Figure 7c reveals that poverty among ST households is highly concentrated in the north and east, particularly in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, Jharkhand, and Odisha, where more than 81 percent of ST households fall into the lowest wealth category. This pattern aligns closely with long-standing regional disparities in land ownership, human capital development, and rural livelihoods. These districts typically lack reliable infrastructure, public health systems, and effective local governance, factors that collectively constrain opportunities for socio-economic advancement.

In contrast, southern and western India, especially districts in Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Maharashtra, and Gujarat, exhibit a lower proportion of poor ST households, often below 36 percent. These areas have benefited from more progressive welfare policies, better education and health infrastructure, and stronger community-based institutions. Figure 7d, which maps the bivariate relationship between poverty levels and health insurance coverage, further corroborates the inverse association observed in the BPL analysis. Districts with a higher concentration of poor ST households primarily in the north and east tend to exhibit markedly low levels of health insurance coverage. This correlation underscores a compounding disadvantage: those most in need of financial protection are least likely to receive it. While some central and northeastern districts show moderate improvements, the positive association between reduced poverty and higher insurance coverage is far more consistent in southern and western India, reinforcing the idea that economic status remains a key determinant of health security access. Importantly, the strength of this relationship is less variable in the south, likely due to more effective state-sponsored insurance schemes (namely, SHIS) and better administrative outreach.

Altogether, Figures 6 and 7 present compelling evidence of a geographically rooted cycle of deprivation. In much of northern and eastern India, ST households are economically marginalized and simultaneously excluded from health insurance protection. These areas represent converging zones of poverty and health insecurity, where existing public schemes are not reaching their intended beneficiaries. On the other hand, southern and western districts exhibit a double advantage lower economic vulnerability and higher health insurance penetration, suggesting that state capacity, local governance, and socio-political integration play significant roles in shaping coverage outcomes.

3.4 Spatial Nexus between Economic Vulnerability and Health Insurance Coverage

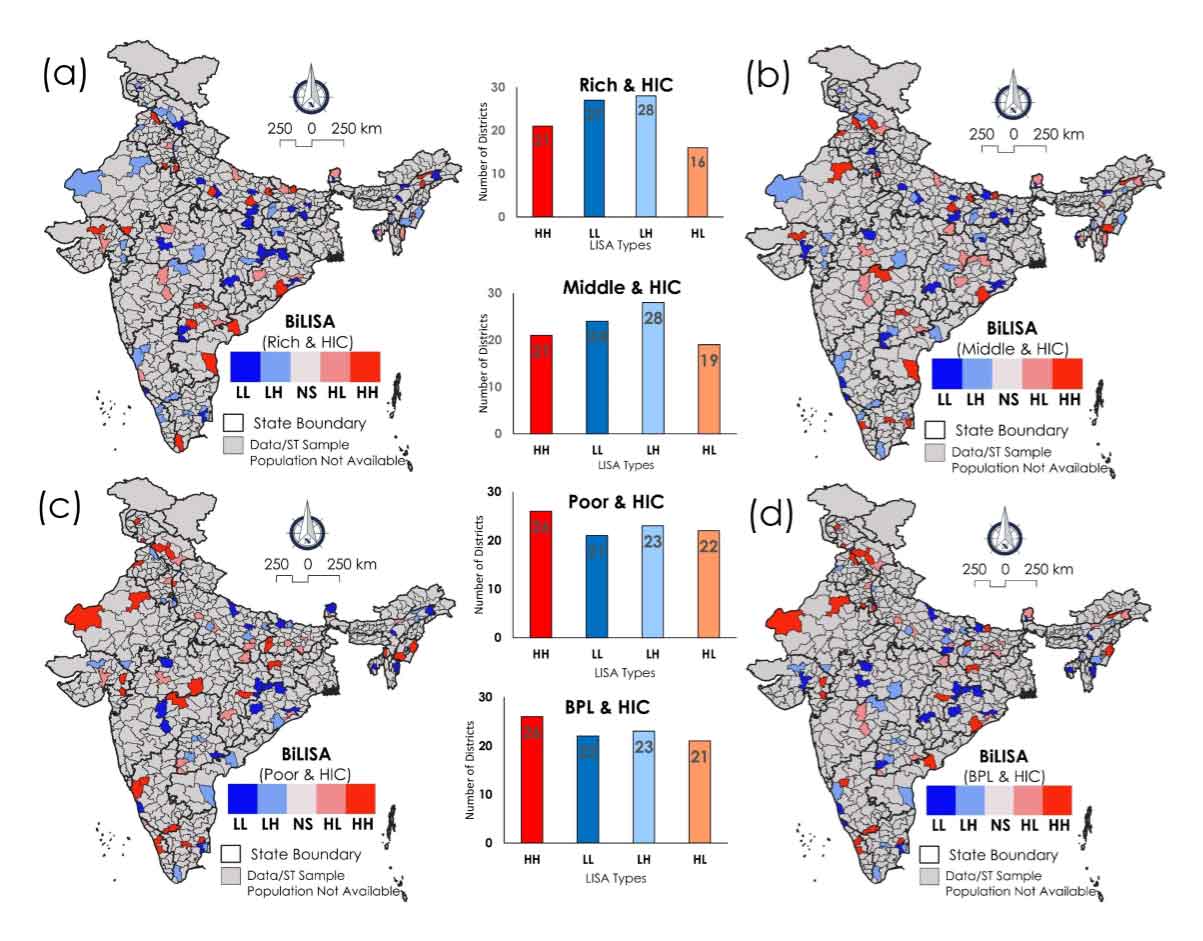

The maps in Figure 8 deepen geographical understanding of the bivariate intersection between economic vulnerability and healthcare access among ST households in India. Together, Figures 8 a-d present compelling evidence of a geographically rooted cycle of deprivation. In much of northern and eastern India, ST households are economically marginalized and simultaneously excluded from health insurance protection. These areas represent converging zones of poverty and health insecurity, where existing public schemes are not reaching their intended beneficiaries. On the other hand, southern and western districts exhibit a double advantage lower economic vulnerability and higher health insurance penetration, suggesting that state capacity, local governance, and socio-political integration play significant roles in shaping coverage outcomes. When these economic indicators are analyzed in tandem with health insurance coverage, they reveal stark regional inequalities and structural disadvantages that disproportionately affect tribal communities in specific parts of the country. A striking pattern that emerges from both maps is the prevalence of districts in northern, eastern, and central India that fall into the “high poverty-low insurance” quadrant. These are districts where large proportions of ST households are economically deprived, either classified under the BPL category or falling into the lowest wealth quintile and simultaneously exhibit poor enrollment in health insurance schemes. This co-location of poverty and exclusion represents the epicenter of structural marginalization. In such districts, ST households not only suffer from a lack of basic resources but are also denied access to one of the key protective mechanisms meant to shield them from health-related financial shocks.

The Rich and HIC map in Figure 8a shows districts where wealth (or economic prosperity) is high, in relation to the health insurance coverage among ST populations. The HH clusters, marked in red, indicate districts where both the rich population and the ST population with high health insurance coverage are concentrated. These clusters are found for 28 districts mainly located in northern, northeastern, and central India. These regions reflect districts where economic prosperity is coupled with better access to health services for marginalized communities. On the other hand, LL clusters, shown in blue, reflect districts with low wealth and low health insurance coverage among STs. These districts are mainly spread across central and southern parts of India, indicating areas where both economic development and health protection for ST communities lag behind. The scattered HL and LH districts reflect transitional zones, where one of the variables (wealth or health insurance coverage) is advanced, while the other is lacking. This categorically indicate regions with economic wealth but insufficient health insurance coverage for STs or areas where health insurance coverage for STs is significant but economic prosperity is lower.

In the Middle and HIC category in Figure 8b, districts with middle-income status are examined alongside the extent of health insurance coverage among the ST population. The HH clusters are more prominent in the northern and northwestern regions, indicating that in these 21 districts, a middle-income population is associated with higher levels of health insurance coverage for STs. These represent districts where moderate economic development has translated into better access to health services for marginalized populations. LL clusters, representing middle-income districts with low health insurance coverage for STs, are more widely dispersed across central and southern India, indicating regions that have moderate economic development but lag in providing health insurance to ST communities. The HL and LH areas are again scattered, reflecting districts that exhibit uneven development between economic status and healthcare coverage for Scheduled Tribes.

In the Poor and HIC map, districts with higher poverty levels are analyzed in conjunction with health insurance coverage among the ST population (Figure 8c). HH clusters in the northern and northwestern regions indicate areas where poverty and high health insurance coverage for STs coexist (for 26 districts). This suggests that despite the overall poverty in these regions, efforts have been made to provide health insurance to ST communities, due to directed health programs. Conversely, LL clusters, representing poor districts with low health insurance coverage for STs, are found in central and eastern India, showing regions where both poverty and lack of health coverage are critical issues.

Figure 8d focus is on districts where a significant portion of the population lives Below the Poverty Line, combined with the level of health insurance coverage for ST households. The HH clusters, which are prominent in the northern and northwestern regions, indicate areas where both high BPL household dominancy and high health insurance coverage for ST populations coincide. This mainly suggest areas where, despite the prevalence of extreme poverty, there has been effective implementation of health insurance schemes for marginalized groups, possibly through government interventions like subsidized health insurance programs for BPL families. LL clusters, found mainly in central and western parts of India, represent districts where both BPL levels and health insurance coverage for STs are low, suggesting areas where both economic upliftment and healthcare access are lagging. The HL and LH areas, where one factor is high and the other low are scattered across various parts of India, indicating uneven progress in terms of poverty reduction and healthcare coverage for Scheduled Tribes.

The bivariate maps also reveal spatial mismatches, where expected correlations are not observed. A few districts in central and northeastern India, for instance, demonstrate high proportions of poor or BPL ST households but moderate-to-high insurance coverage. These “high poverty-high coverage” zones indicate that with the right policy instruments and delivery mechanisms, economic deprivation need not translate into health insecurity. These regions could be benefiting from effective NGO partnerships, community health workers, or localized innovations in insurance outreach. They deserve further qualitative exploration to identify best practices.

On the other hand, some districts with relatively low poverty still report low insurance coverage, falling into the ‘low poverty-low coverage’ category. These anomalies suggest administrative neglect, weak political will, or lack of program visibility despite the economic potential of the community. Such mismatches highlight the importance of looking beyond economic indicators alone when designing interventions and considering socio-cultural or political constraints that may hinder coverage. These spatial analyses underscore the varying relationships between socioeconomic conditions and health insurance coverage among marginalized groups like Scheduled Tribes in India. From this analysis, the findings suggest that, HH clusters in the northern, northwestern, and central parts of India indicate regions where there is either wealth or higher poverty, coupled with significant health insurance coverage for ST populations. These areas may reflect regions where health insurance programs for Scheduled Tribes are effective, possibly due to targeted government health schemes. In contrast, LL clusters are more spread across central, southern, and western India, reflecting districts that are struggling with both lower economic status and poor health insurance coverage for the ST population. These areas could be priority regions for policies that aim to both reduce poverty and improve healthcare access for ST communities.

Table 2. Typology of local realities based on the directions and intensity of GW correlations

|

Type

|

Wealth-Insurance Correlation

|

Implications

|

|

Type A

|

Strong positive

|

Prosperity is leveraged into protection (namely, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh) - maintain momentum.

|

|

Type B

|

Weak/negative

|

Wealth does not translate to insurance (namely, Rajasthan, UP) - improve outreach and delivery.

|

|

Type C

|

Middle-income gaps

|

Coverage breaks for non-poor, non-rich (namely, Odisha, MP) - address policy blind spots.

|

|

Type D

|

Strong negative (BPL-poor)

|

Poorest excluded from protection (namely, Jharkhand, Bihar) - urgent corrective action needed.

|

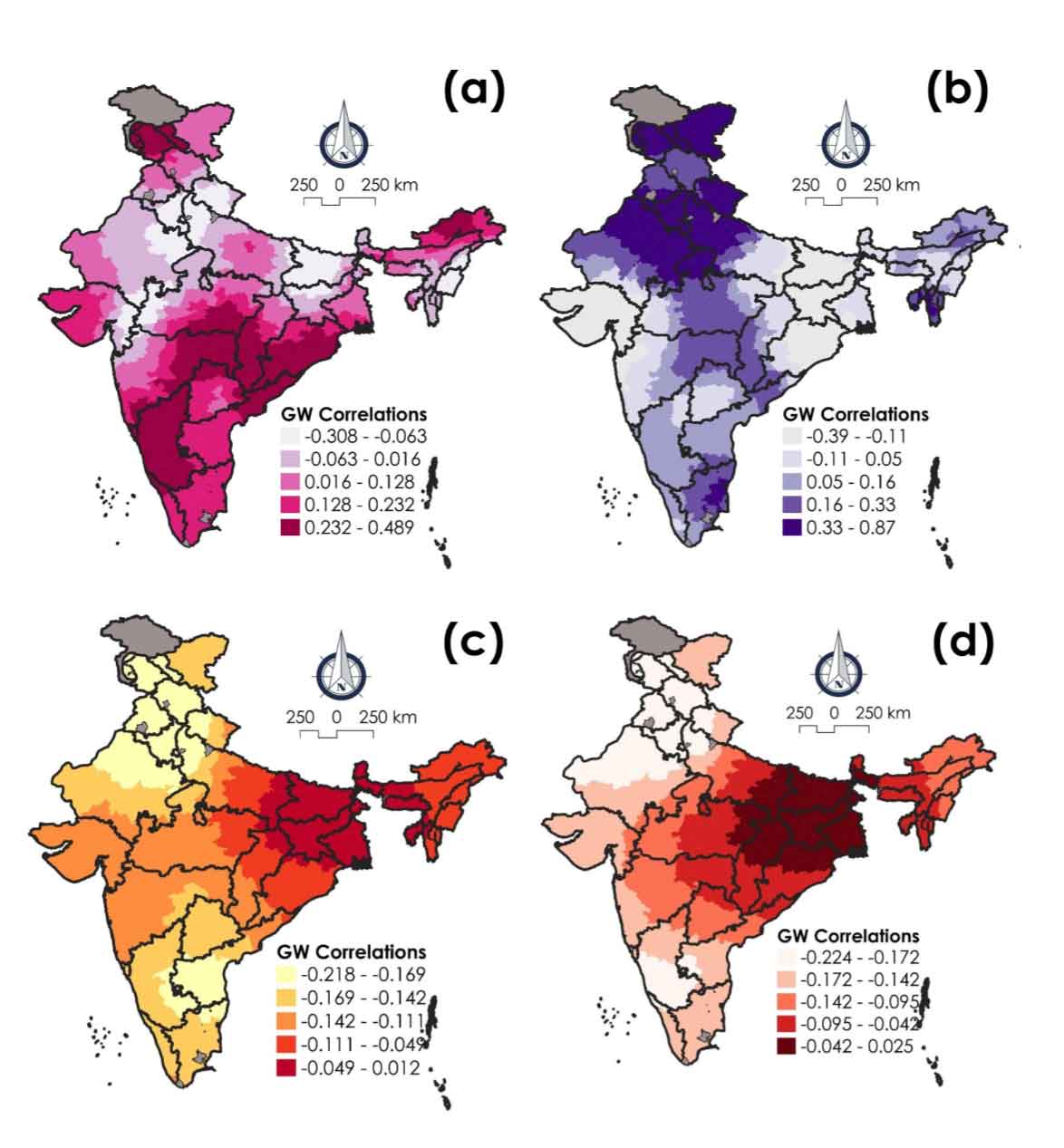

3.5 Localized Correlation between Health Insurance with Wealth Dynamics

The Geographically Weighted (GW) correlation analysis presented in Figure 9 and Table 2 offers a powerful spatial perspective on how different wealth categories (rich, middle, poor, and BPL) relate to health insurance coverage across India’s ST population. In examining GW correlations between wealth gradients (rich, middle, poor, and BPL) and insurance coverage, we are not merely asking, ‘does wealth lead to coverage?’ Instead, we are exploring ‘where’ wealth matters more or less in securing health protection for tribal populations. Unlike global correlation measures that provide a single average value, GW correlations allow for the estimation of localized relationships, reflecting context-sensitive interdependencies that vary across geographic space.

The map reveals a notable concentration of positive GW correlations in southern and parts of central India, particularly in Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Chhattisgarh. In these regions, there is a strong positive spatial association between wealth and insurance coverage, i.e., ST households classified as wealthy are more likely to be covered by health insurance. This suggests a clear gradient of advantage, where higher socio-economic status confers better access to health protection. This spatial alignment also indicates that in these regions, economic capital translates more directly into health security, reinforcing the structural benefits of relative affluence within ST communities. In contrast, northern regions, particularly Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, and parts of Gujarat, display weak or even negative correlations between wealth and insurance coverage. This suggests that economic advantage among STs in these areas does not consistently lead to improved access to health insurance.

Table 3: Key policy recommendations for improving tribal health and insurance access

|

Policy area

|

Key recommendations

|

Supporting rationale/impact

|

|

Increased Public Expenditure and Budget Allocation

|

- Substantially increase per capita government expenditure on tribal health, with 70 percent dedicated to primary healthcare. Allocate at least 8.6 percent of the national health budget specifically for tribal health.

- Ensure strict adherence to Tribal Sub Plan (TSP) guidelines to prevent resource diversion.

|

Addresses historical underfunding and ensures dedicated resources commensurate with population share, directly affecting service availability and quality.

|

|

Dedicated Policy and Institutional Framework

|

- Establish a National Institute for Tribal Health with field stations.

- Frame and implement a specific, culturally sensitive Tribal Health Policy and a coordinated action plan.

- Ensure representation of ST experts in policymaking bodies.

|

Moves beyond generic rural health approaches to tailored, evidence-based interventions that respect unique tribal contexts and needs, fostering ownership and effectiveness.

|

|

Infrastructure and Service Delivery Improvements

|

- Address critical shortfalls in Health Sub-Centers, Primary Health Centers, and Community Health Centers.

- Recruit and retain adequate numbers of allopathic doctors and specialists in tribal areas.

- Leverage information technology (telemedicine, mobile health) to bridge geographical gaps.

- Develop behavior change models to encourage utilization of modern medicine alongside traditional practices.

|

Improves physical access, quality of care, and addresses personnel shortages. Technology can overcome geographical isolation. Culturally sensitive approaches build trust and improve health-seeking behavior.

|

|

Financial Protection and Health Insurance

|

- Provide comprehensive health insurance for all tribal people, potentially through dedicated schemes (for instance, Aadivasi Aarogya Bima Yojana, ST health cards).

- Ensure government subsidization for vulnerable groups to make insurance truly accessible.

|

Mitigates the catastrophic financial burden of out-of-pocket expenditures, preventing impoverishment and enabling access to necessary care for the quadruple disease burden.

|

|

Data and Research

|

Prioritize and fast-track the collection and analysis of disaggregated data on tribal health status and underlying social, cultural, and economic determinants.

|

Fills critical data gaps, allowing for evidence-based policy design, targeted interventions, and effective monitoring of progress for diverse tribal groups.

|

|

Holistic Socio-economic Development

|

Focus on enhancing the overall development of tribal populations to bridge existing inequalities in education, economic attainment, and access to public utilities.

|

Addresses the root social determinants of health, recognizing that health outcomes are inextricably linked to broader socioeconomic conditions and systemic integration.

|

The spatial relationship between middle-wealth ST households and health insurance coverage shows considerable regional variability. Positive correlations are observed in northern states like Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, and Uttarakhand, where middle-class ST populations appear to benefit from moderate access to insurance. This may reflect relatively better outreach, higher educational levels, or proactive state health policies in these regions.

However, in much of central and eastern India, including Odisha, West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh, and parts of Chhattisgarh, the correlation either weakens or becomes negative. This suggests that even moderate wealth does not shield ST communities from exclusion, indicating that structural vulnerabilities persist regardless of relative economic positioning. This points to non-economic barriers, such as information asymmetries, lack of documentation, or cultural disconnection from institutional systems, that continue to affect insurance enrollment and utilization.

Perhaps the most alarming pattern revealed by the GW correlation maps concerns the poor and BPL ST households. In central and eastern India, particularly in Jharkhand, Bihar, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and parts of West Bengal, there are strong negative correlations between poverty levels and health insurance coverage. This means that poorer ST populations in these regions are significantly less likely to be covered by any form of health insurance, despite being the most in need. This spatial mismatch signals a serious policy failure: the very groups that government health insurance schemes are designed to protect are the ones most likely to be left behind.

3.6 Implications for Policy and Interventions

In the study, the identified regional disparities in wealth, poverty, and health insurance coverage among ST households in India at the district level impose the need of inclusive policy interventions at the local scale. The confluence of the severe quadruple disease burden, profound systemic barriers to healthcare access, and critically low health insurance penetration presents an urgent and complex policy challenge for India. The current situation, marked by historical neglect and fragmented approaches, demands a fundamental shift in policy orientation towards tribal health. Addressing these deeply entrenched issues requires a comprehensive, multi-pronged policy approach that transcends traditional health sector boundaries and embraces a true equity focus. The fundamental issue at play is deep-seated health inequity, stemming from centuries of historical and systemic disadvantages. This necessitates a “whole-of-government” or truly multi-sectoral approach where various ministries and departments coordinate their efforts and resources (Table 3). The findings suggest that, for northern and eastern districts, where economic and healthcare vulnerabilities are most pronounced, there is an urgent need for policies that promote strategic economic development, improve access to quality education and employment opportunities, and enhance social protection measures, including greater penetration of marginalized segments under comprehensive health insurance schemes. Such interventions potentially help revitalization ST households out of poverty and reduce their vulnerability to health and financial shocks.

In contrast, southern and western districts, while relatively better off, still require policies that ensure the sustainability of their socio-economic gains and address any emerging inequalities. Expanding health insurance coverage and improving the quality of healthcare services can further enhance the well-being of ST households in these regions. The analysis reveals significant spatial disparities in health insurance coverage for ST households, with southern and western states generally exhibiting better coverage outcomes than northern, northeastern, and central regions. State-Specific Health Insurance Schemes (SHIS) appear to be particularly effective in expanding coverage for ST households, especially in regions like Himachal Pradesh and Bihar, suggesting that these programs may be more directed to the needs of local populations than national schemes.

Conversely, states like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Madhya Pradesh consistently demonstrate low health insurance coverage across various schemes. These underperforming regions require stronger policy interferences, including targeted awareness campaigns, improved access to government health schemes, and enhanced healthcare infrastructure, to ensure that ST populations receive adequate health insurance coverage. Moreover, given the low coverage rates under schemes like CGHS and ESIS, which cater primarily to the formal sector, there is an urgent need for new insurance programs specifically designed for ST households engaged in informal employment.