|

Name of the Author

|

Parameters/Criterions

|

Data

|

Sampling

|

Analytical methods in laboratory

|

Methodology /Techniques

|

Objectives

|

Purposes

|

Study area

|

|

Chatterjee et al., 2009

|

pH, EC, TDS, TH, Na⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, CO₃²⁻, NO₃⁻, and F⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

79 Samples-out of them 26 surface water, 41 subsurface water and 12 mine waters

|

--

|

GIS, WQI

|

To make a ground water quality assessment using GIS

|

Drinking and Irrigation

|

Dhanbad district, Jharkhand, India,

|

|

Baghvand et al., 2010

|

pH, EC, TDS, Major Cations (Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺) and Major Anions (CO₃²⁻, HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, Cl⁻)

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

20 Boreholes considered for sampling

|

Digital pH and EC meter, Flame Photometry, Flame atomic absorption Spectrometer, HACH DR/2000

|

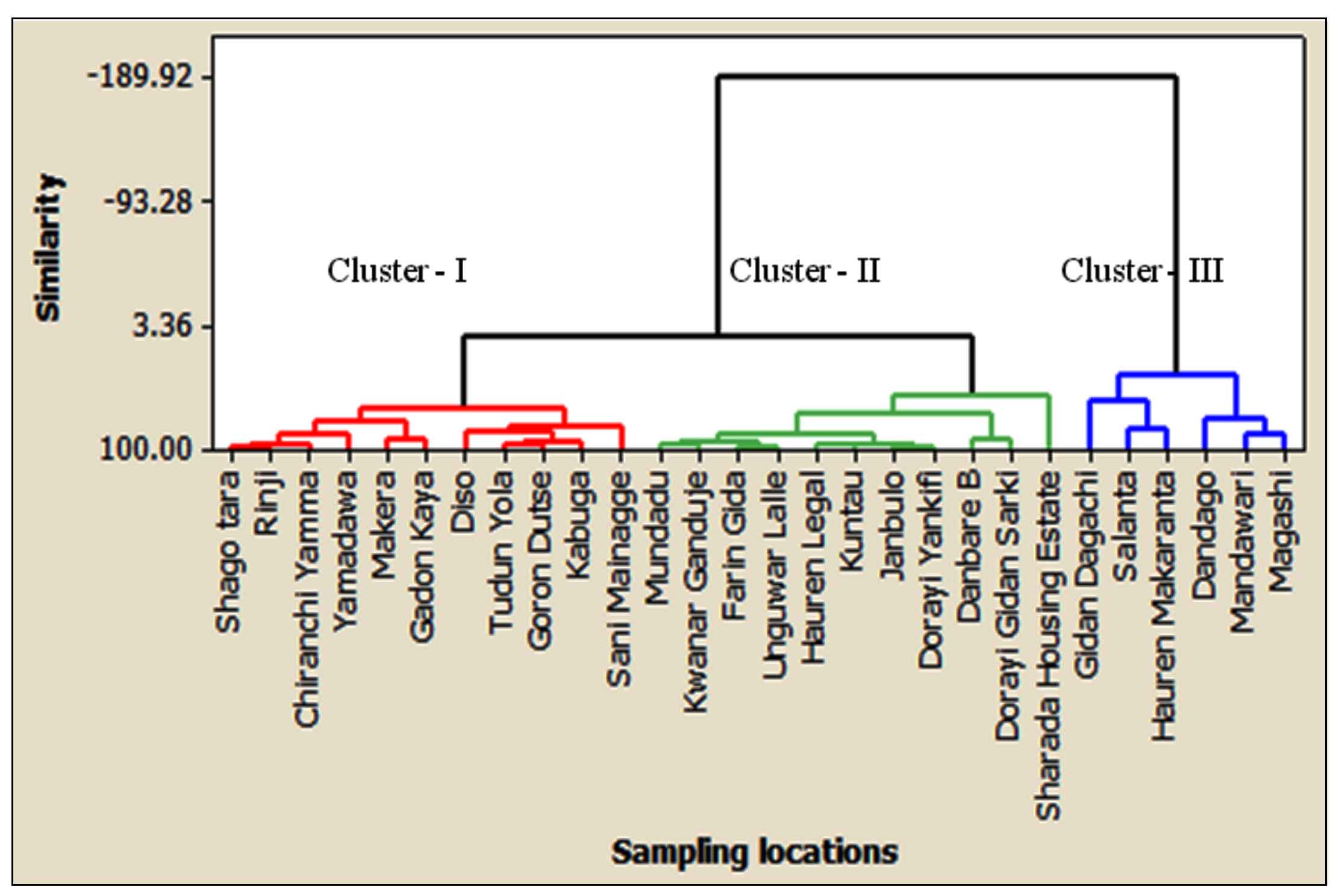

Piper trilinear diagram, Schoeller diagram, Wilcox diagram, Dendrogram diagram, Cluster analysis

|

To analyse the hadrochemical characterizations of groundwater for the suitability analysis

|

Groundwater suitability analysis

|

Iran Central Desert

|

|

Vasanthavigar et. al., 2010

|

Na⁺, Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺, K⁺, HCO₃⁻, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, PO₄³⁻, H₄SiO₄, F⁻, pH, EC, and TDS

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

148 (bore holes) groundwater samples

|

Digital spectrophotometer, Flame photometer, Titrimetric method

|

SAR, RSC, SSP, WQI, Piper trilinear diagram, Box plots

|

To evaluate water quality index for groundwater quality assessment

|

Health risks assessment

|

Thirumanimuttar sub-basin, Tamilnadu, India

|

|

Prashant et al., 2012

|

pH, EC, TDS, TH, HCO₃⁻, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻, F⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

22 shallow open dug wells samples

|

|

Piper trilinear diagram, Wilcox diagram, PI, SAR, MH

|

To evaluate the spatial extent of groundwater quality and its suitability for drinking and agricultural uses in the costal stretch

|

Drinking and Agriculture

|

Alappuzha District, Kerala, India

|

|

Singh et al., 2012

|

pH, EC, TDS, TH, Na⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, CO₃²⁻, NO₃⁻, and F⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

15 groundwater samples were collected in August 2010 from shallow and deep bore hand-pumps

|

EDTA titrimetric method, UV–Visible spectrophotometer model, Sampling and analytical procedure

|

Correlation analysis, Base-exchange indices, Meteoric genesis indices, Piper trilinear diagram, Salinity index, Chlorinity index, Sodicity index

|

To evaluate the groundwater quality for drinking, domestic and irrigation purposes

|

Drinking Domestic and Irrigation

|

Lutfullapur Nawada, Loni, District Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh, India

|

|

Nagarjuna et al., 2014

|

pH, EC, TH, TDS, TA, NCH, SAR, SP, RSC

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

40 Samples

|

pH/EC/TDS Meter Indices of exchange

|

SAR, RSC, Indices of exchange magnesium ratio, KR, Saturation index, Gibbs diagram Piper trilinear diagram, Wilcox diagram, Permeability Index (PI)

|

Assessment of ground water quality for irrigation

|

Irrigation

|

Bandalamottu lead mining area Guntur District, Andhra Pradesh South India

|

|

Chung et al., 2014

|

Na⁺ > Ca²⁺ > Mg²⁺ > K⁺; Cl⁻ > HCO₃⁻ > SO₄²⁻ > NO₃⁻ > F⁻; and Ca(HCO₃)₂, CaCl₂, NaCl

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

40 - wells Samples

|

Ion chromatography (IC, Water 431), Standard analytical methods, WATEQ4F geochemical model

|

WQI, Wilcox diagram, Gibbs diagram, Piper trilinear diagram, PI, SAR, RSC, Index of Base Exchange, Chloro-alkaline indices (CAI-I and CAI-II), Saturation index (WATEQ4F)

|

To assess the present quality of groundwater and determine the suitability of groundwater use for various purposes

|

Drinking and Domestic

|

Busan City, Korea

|

|

Tiwari and Singh, 2014

|

pH, EC, TDS, TH, Na⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, CO₃²⁻, NO₃⁻, and F⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

55 groundwater samples

|

UV-VIS spectrophotometer

|

Piper trilinear diagram, Relative standard deviation, SI, Mineral Equilibrium, SAR, KR, Wilcox diagram, USSL diagram

|

To identify the factors controlling groundwater composition and assess its suitability for domestic and irrigation uses

|

Domestic and irrigation

|

Pratapgarh District, Uttar Pradesh

|

|

Aly et al., 2015

|

EC, pH, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

28 groundwater samples collected from tube wells

|

Phenoldisulfonic acid method, Turbidity method

|

WQI Piper trilinear diagram, Gibbs diagram, Schoeller diagram, Durov’s diagram, SAR, KR, IBE

|

To assess groundwater quality for drinking and evaluate its hydro chemical characteristics

|

Drinking

|

Hafar Albatin, Saudi Arebia

|

|

Batabyal and Chakraborty, 2015

|

pH, TDS, TH, HCO₃⁻, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻, F⁻, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺, Mn²⁺, Zn²⁺

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

28 tube wells

|

-

|

WQI, Correlation coefficient matrix, triangulation with linear interpolation method

|

To assess groundwater quality for drinking

|

Drinking purposes

|

Kanksa-Panagarh area, Bardhaman District of West Bengal.

|

|

Sako et al., 2016

|

pH, EC, COD, TDS, TH, HCO₃⁻, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻, F⁻, NO₂⁻, NH₄⁺, PO₄³⁻, Al, Asᵀ, Cu, Mnᵀ, Niᵀ, Cr, Pb, Zn, Na⁺/Cl⁻, Na⁺/Ca²⁺, TCᶜ

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

6 dug wells and 7 boarewells samples

|

ICP-OES-Inductively, coupled plasma- optical emission spectroscopy, ICP-MS-Inductively, coupled-mass spectroscopy, Colometric method (APHA5220D)

|

Multivariate Statistic techniques, Piper trilinear diagram, PCA, Boxplots diagram

|

To assess the groundwater suitability for human consumption

|

Drinking

|

Bombore gold mineralized zone, Central Burkina Faso

|

|

Houatmia et al., 2016

|

pH, CaCO₃, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, Na⁺, HCO₃⁻, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

39 water sample collected from Wells

|

Colorimetric method, Nephelometric methods, Volumetric method

|

WQI, KR, PI, SAR, RSC, MH, Wilcox diagram, Piper trilinear diagram, Saturation index (PHREECQ)

|

To assess the groundwater geochemistry and evaluate its suitability for drinking and irrigation purposes

|

Drinking and Irrigation

|

North- eastern, Tunisia

|

|

Li et al., 2016

|

pH, EC, TDS, TH, Na⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, CO₃²⁻, NO₃⁻, and F⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

31 groundwater samples -wells and hand pumping

|

Flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry, EDTA titration, Ion chromatography Traditional titrimetric method, spectrophotometry

|

HRA, Gibbs diagram, SAR, RSC, SSP, USSL diagram, Wilcox diagram, Piper diagram

|

To assess overall groundwater quality for irrigation and drinking water intake and dermal contact for different age group

|

Drinking and Irrigation

|

Northwest China

|

|

Islam et al., 2017

|

Temperature, pH, EC, TDS, Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻, HCO₃⁻, Br⁻, and trace elements such as As, Pb, Li, Rb, Ba, Be, Co, Mn, Ti, Cd, and Se.

|

Field Survey Primary data

|

18 groundwater samples collected from tube wells

|

pH meter, Portable meter, Portable EC meter, TDS meter, Gallenkamp Flame Analyzer

|

Soluble sodium percentage (SSP), Sodium absorption ratio-(SAR), Magnesium absorption ratio (MAR), Residual sodium carbonate (RSC), Kelley’s ratio (KR), Wilcox diagram, USSL diagram

|

To assess the hydro chemical characteristics and water quality, and evaluate their impact on human health

|

Health risk assessment

|

Patuakhali District Southern Coastal Region of Bangladesh

|

|

Narsimha and Sudarshan, 2017

|

pH, EC, TDS, TH, CO₃²⁻, NO₃⁻, F⁻, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

104 groundwater samples

|

Flame photometry, Titrimetrically using standard EDTA Method, UV-Visible Spectro photometer, Fuoride ion-selec- tive electrode

|

Piper trilinear diagram, Correlation analysis, Gibbs diagram

|

To understand fluoride distribution in groundwater, its relationship with major ions, and identify high-fluoride zones

|

Human health risk assessment

|

Siddipet, Telangana State, India

|

|

Adimalla and Venkatayogi, 2017

|

pH, EC, TH, TDS, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

194 groundwater Samples

|

pH/EC/TDS Meter, Titration method, Flame Photometer, Fluoride Ion-selective electrode, UV- Visible spectrophotometer

|

Gibbs diagram, Piper trilinear diagram

|

Mechanism of Fluoride enrichment in groundwater of hard rock aquifers

|

Fluoride concentrations

|

Medak, Telangana State, South India

|

|

Kaur et al., 2017

|

Na⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, Cl⁻, pH, EC, TDS, Temperature

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

24 (well) groundwater samples

|

Water quality analyzer (ELICO), Standard methods Acid titration method, Argentometric method, SPADNS calorimetric method, Turbidimetric method, Stannous chloride method, UV–visible spectrophotometer Flame Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer

|

ELICO- Water quality analyser (PE 138.), American Public Health Association, Pie -Diagram, Piper trilinear diagram, Gibb’s diagram, SAR, Sodium percentage (SP), Magnesium ratio (MR), Corrosivity ratio (CR), Wilcox diagram, SI

|

To assess the groundwater quality for drinking and irrigation purposes

|

Drinking and Irrigation

|

Malwa region southwestern part of Punjab, India

|

|

Ayed et al., 2017

|

Na⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, Cl⁻, pH, EC, TDS, Temperature

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

47(wells) groundwater samples

|

Calibrated pH meters, Conductivity meter, Titration method, Ionic equilibrium, Diagram” and “Excel 2016” Shapiro–Wilk test

|

Multivariate statistical analysis, Hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA), PCA, Piper trilinear diagram, Dendrogram diagram, PI, SI, SAR, SP, Magnesium Percent

|

To assess the water quality and to determine the main hydro-chemical process which affect groundwater

|

Planning and Management

|

The Maitime Djeffara shallow aquifer (Southeastern Tunisia)

|

|

Khan and Jhariya, 2017

|

pH, EC, TDS, TH, Na⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, CO₃²⁻, NO₃⁻, and F⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

34 groundwater samples

|

--

|

Standard methods, GIS, WQI

|

To assess the groundwater quality for drinking purpose

|

Drinking

|

Raipur City, Chhattisgarh

|

|

Tiwari et al., 2017a

|

pH, EC, TDS, TH, Na⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, CO₃²⁻, NO₃⁻, and F⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

55 groundwater samples -shallow (dug wells) and deep aquifers (tube well/hand pumps)

|

Portable conductivity, pH meter, Acid titration method, UV–VIS spectrophotometer, Ion chromatograph, Flame atomic absorption spectrophotometer

|

WQI, GIS Piper trilinear diagram, Gibbs diagram, Statistical analysis, Inverse distance weighted (IDW)

|

To assess the groundwater quality for its suitability to drinking

|

Drinking

|

Pratapgarh district, in India

|

|

Tiwari et al., 2017b

|

pH, EC, TDS, F⁻, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, TH, SAR, RSC, PI, MH, KI, and Silica

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

25 Surface sample collected from river, ponds and canals

|

Portable Conductivity, pH Meter, Acid titration method, Molybdosilicate methods, Ion chromatograph (Dionex DX-120), Flame atomic absorption spectrophotometer

|

WQI, Piper trilinear diagram, Gibbs diagram, Correlation coefficient matrix, Interpolation techniques

|

To evaluate the water quality of surface water

|

Utilization and planning

|

Pratapgarh district, Uttar Pradesh

|

|

Zhang et al., 2018

|

pH, TH, TDS, Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, CO₃²⁻, HCO₃⁻, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃–N, NO₂–N, NH₄–N

|

Primary data Field Survey

|

47 groundwater samples collected from pumping wells

|

Portable pH mete, EDTA titrimetric method, Routine titrimetric methods, Fame atomic absorption spectrometry

|

CBE, Comprehensive Water Quality Index Method (CWQI), Piper trilinear diagram, Gibbs diagram

|

To evaluate groundwater quality for human health risks assessment

|

Health risks assessment

|

Jinghui Canal, Irrigation area of the loess region, Northwest China

|

|

Adimalla, 2018

|

TDS, TH, Ca²⁺, Na⁺, Mg²⁺, Cl⁻, K⁺, NO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, and F⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

194 Groundwater samples

|

Interpolation technique, Inverse distance-weighted

|

SAR, RSC, Magnesium hazard (MH), PI, Piper trilinear diagram, Gibbs diagram, USSL diagram

|

To assess groundwater quality, health risks, monitoring efficiency, and vulnerability for informed policy-making

|

Health risks assessment

|

Semi-Arid Region of South India

|

|

Adimalla et al., 2018

|

pH, TDS, TH, HCO₃⁻, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻, F⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

105 Groundwater samples

|

pH/EC/TDS Meter

|

WQI Piper trilinear diagram, Gibbs diagram, SAR, RSC, MH, KR, Wilcox diagram, USSL diagram, Chloro-alkaline indices (CAI-I and CAI-II)

|

To evaluation of groundwater quality for Drinking and irrigation purpose

|

Drinking and Irrigation

|

Central Part of Telangana

|

|

Adimalla et al., 2018b

|

pH, EC, TDS, TH, HCO₃⁻, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻, F⁻, (TZ⁺), and (TZ⁻)

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

35 groundwater samples

|

pH/EC/TDS meter, EDTA titrimetric Method, Flame photometric, UV visible spectrophotometer, Standard methods

|

GIS (Kriging method), Ionic balance error, Gibbs diagram, Piper trilinear diagram, Scatters plots

|

To understand the correlation between fluoride and other chemical indices, hydro geochemistry of fluoride occurrence and its distribution

|

Fluoride enrichments

|

Peddavagu in Central Telangana (PCT)

|

|

Khan and Jhariya, 2018

|

pH, EC, TDS, TH, HCO₃⁻, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻, F⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

100 groundwater samples

|

Titration, Flame photometer, UV-VIS spectroscopy, Atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS)

|

Gibbs diagram, Piper trilinear diagram, Scatter diagram, Schoeller diagram, SAR, PI, USSL diagram

|

To assess groundwater quality for drinking and irrigation Purpose

|

Drinking and Irrigation

|

Raipur City, Chhattisgarh

|

|

Adimalla et al., 2018b

|

pH, EC, TDS, TH, Na⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, CO₃²⁻, NO₃⁻, and F⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

34 groundwater samples-borewells

|

pH meter, Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), Flame photometric, Titration method, ISE meter

|

HHRA, Hazard quotient (HQ), Total hazard index, IBE

|

Evaluation of groundwater contamination for fluoride and nitrate

|

Contamination- fluoride and nitrate

|

semi-arid region of Nirmal Province, South India

|

|

Adimalla and Venkatayogi, 2018

|

Na⁺, Ca²⁺, K⁺, Mg²⁺, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, CO₃²⁻, NO₃⁻, F⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

34 groundwater samples (bore well/hand pumps)

|

EDTA titration, Flame Photometer, Fluoride ion-selective electrode

|

Standard methods, Piper trilinear diagram, Gibbs diagram, Box plot

|

To assess fluoride concentration in groundwater for study area

|

Fluoride concentration

|

Basara, Adilabad District, Telangana State, India

|

|

Subba Rao et al., 2018

|

pH, EC, TDS, TH, Na⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, CO₃²⁻, NO₃⁻, and F⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

30 (dug wells) groundwater samples

|

Portable meters, EDTA titration Method, Flame photometer, Volumetric method, UV-spectrophotometer, Titration method

|

Pollution index of groundwater, Bivariate and Piper trilinear diagram, ANOVA test, IBE

|

To evaluate the quality of groundwater for drinking water quality limits, and unhide the sources responsible for variation of quality of groundwater

|

Drinking

|

Rural part of Telangana State, India

|

|

Madhav et al., 2018

|

pH, EC, TDS, TH, Na⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, CO₃²⁻, NO₃⁻, and F⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

20 groundwater samples

|

pH and conductivity meters,

|

WQI, Piper trilinear diagram, Gibbs diagram, Wilcox diagram, PI, KR, USSL diagram

|

Geochemical assessment of groundwater suitability for drinking and irrigation purpose

|

Drinking and Irrigation

|

Rural areas of Sant Ravidas Nagar (Bhadohi), Uttar Pradesh

|

|

Jafari et al., 2018

|

pH, EC, TDS, TH, Na⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, CO₃²⁻, NO₃⁻, and F⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

30 groundwater samples

|

Ion meter model, UV–Vis spectrophotometer, flame photometer model, EDTA titrimetric method

|

RSC, PI, KR, MH, SP, SAR, SSP

|

Groundwater quality assessment for drinking and agriculture purposes

|

Drinking and agriculture

|

Abhar city, Iran

|

|

Chaudhary and Satheeshkumar, 2018

|

pH, EC, TDS, TH, Na⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, CO₃²⁻, NO₃⁻, and F⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

300 groundwater samples collected from hand pumps

|

Spectrophotometric techniques

|

RSC, PI, KR, Piper trilinear diagram, Wilcox diagram, USSL diagram, Gibb’s diagram, MH, SP, SAR, SSP, Potential salinity

|

To assess the groundwater quality for drinking and agriculture purposes

|

Drinking and agriculture

|

Arid areas of Rajasthan, India

|

|

Adimalla et al., 2019

|

EC, pH, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

107 Groundwater samples

|

pH/EC/TDS, Meter, Flame photometer meter, UV-visible spectrophotometer, Orion 4-star meter, pH/ISE meter

|

WQI, Piper trilinear diagram, Gibbs diagram, Boxplots diagram

|

To evaluate groundwater quality and assess non-carcinogenic risks from fluoride-rich water consumption

|

Health risks assessment and fluoride consumption

|

Shasler Vagu (SV) Watershed of Nalgonda, India

|

|

Adimalla and Qian, 2019

|

pH, EC, COD, TDS, TH, HCO₃⁻, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻, F⁻, NO₂⁻, NH₄⁺

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

61 groundwater Samples collected from hand pumps and bore wells

|

Portable pH/EC/TDS meter, Titration method, UV–visible Spectrophotometer, Flame photometer

|

IBE, WQI, HRA

|

To assess the non-carcinogenic health risks associated with groundwater quality for drinking purposes

|

Health risks assessment

|

Nanganur region, Telangana State, South India

|

|

Adimalla, 2019

|

pH, TDS, SO₄²⁻, Cl⁻, NO₃⁻, F⁻, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, EC, TH, HCO₃⁻, SAR

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

194 groundwater samples were collected: 160 granitic, 24 basaltic, and 10 lateritic aquifers

|

pH/EC/TDS meter, EDTA., AgNO3 titration, Fame photometer,

|

WQI, KR, SAR, RSC

|

To assess groundwater quality for drinking and agricultural purposes and evaluate the health risks assessment

|

Drinking and Agriculture

|

Semiarid region of south India

|

|

Egbueri, 2019

|

Na⁺, Ca²⁺, K⁺, Mg²⁺, SO₄²⁻, Cl⁻, NO₃⁻, HCO₃⁻, and Ca²⁺

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

20 groundwater samples -out of them 3 hand-dug wells and 17 from boreholes

|

pH meter, Standard testing methods, Titration method, Flame photometer, Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (AAS)

|

PIG, Ecological risk index, Hierarchical cluster analysis, Piper trilinear diagram, Pollution index

|

To examine the drinking water quality of the groundwater

|

Drinking

|

Ojoto suburban in southeast Nigeria

|

|

Adimalla and Li, 2019

|

pH, EC, TDS, TH, Na⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, CO₃²⁻, NO₃⁻, and F⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

105 groundwater

|

UV-visible spectrophotometer, pH/EC/TDS meter’ Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), Flame photometric,

|

Piper trilinear diagram, Gibbs diagram, Total Hazard Index, HQ, IBE, CAI

|

To delineate occurrence of fluoride and nitrate contamination and understand the hydro chemical processes responsible for their enrichment

|

contamination-fluoride and nitrate

|

The rock-dominant semi-arid region, Telangana State, India

|

|

Adimalla, 2019

|

pH, EC, TDS, TH, Na⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, CO₃²⁻, NO₃⁻, and F⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

194 (bore/hand pumps) groundwater samples

|

Digital pH/EC/TDS meter, UV-visible spectrophotometer, EDTA titrimetric method, Flame photometer, Ion-selective electrode method

|

GIS, WQI, Pollution index, Piper trilinear diagram, Gibbs diagram, IBE

|

To assess the overall suitability of groundwater for drinking; and to evaluate groundwater quality comprehensively

|

Drinking

|

the hard rock terrain of South India

|

|

Adimalla et al., 2020

|

pH, EC, TDS, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻, NO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, F⁻

|

Primary data (Field survey)

|

43 groundwater samples

|

|

Pollution Index (PIG), Principal component analysis (PCA)

|

The pollution index of groundwater and evaluation of potential human health risk

|

Human health risk

|

Hard rock terrain of south India

|

|

Adimalla et al., 2020

|

pH, EC, TDS, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻, NO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, F⁻

|

Field Survey Primary Data

|

43 samples

|

Titrimetric methods, Flame photometer, UV - Visible spectrophotometer,

|

PIG, Charge balance errors (CBE), Gibbs diagram, Chadha diagram, Ion – selective electrode method (ISE), PCA

|

To assess groundwater quality for fluoride and nitrate, and evaluate their associated health risks for residents

|

Health risk assessment

|

The Northern part of the Nalgonda district, south of Telangana State, India

|

|

Subba Rao et al., 2020

|

pH, TDS, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, HCO₃⁻, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻, F⁻

|

Primary data Field survey

|

30 groundwater sample

|

Portable meters, EDTA titration method, Flame photometer, HCl volumetric method, AgNO3 titration method, Colorimetric method

|

Ionic Balance Error (IBE), Entropy Water Quality Index (EWQI), PCA, Chadha’s diagram

|

Assessment of groundwater quality for drinking and domestic purposes

|

Drinking and domestic purposes

|

Wanaparthy District, Telangana State, India

|

|

Zolekar et al., 2020

|

TDS, TH, Ca²⁺, Na⁺, Mg²⁺, Cl⁻, K⁺, NO₃⁻, and SO₄²⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

61 Groundwater samples

|

pH/EC/TDS meter, Ionc chromatograph, Flame atomic absorption spectrophotometer, EDTA titrimetric

|

GIS Water Quality Index (WQI), Piper trilinear diagram, Gibbs Index

|

To evaluate the groundwater quality for drinking and agriculture uses

|

Drinking and agriculture

|

Nashik District in Maharashtra India

|

|

Singh et al., 2020

|

pH, EC, TDS, TH, HCO₃⁻, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

50 groundwater samples

|

Potable kit, UV spectrophotometric method, Titration method, Flame photometer method

|

USSL- diagram, Wilcox diagram, Piper trilinear diagram, Gibbs diagram, Durov diagram, Chloralkaline Index, PI, SAR, Soluble sodium percentage (SSP), MH, Salinity and Alkalinity Hazard (SAH), Sodium Hazard (SH),

|

To evaluate of groundwater quality for suitability of irrigation purposes

|

Irrigation

|

Udham sigh Nagar, Uttarakhand

|

|

Adimalla et al., 2020

|

pH, EC, TDS, TH, HCO₃⁻, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻, F⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

105 groundwater samples

|

pH/EC/TDS meter, Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, Flame photometer, UV–visible spectrophotometer, Ion-selective electrode,

|

WQI, SAR, RSC, MH, KR, Kriging interpolation technique

|

To analyse overall groundwater quality and evaluate its suitability for drinking and irrigation purposes

|

Drinking and Irrigation

|

Central Telangana, India

|

|

Aher et al., 2022

|

pH, EC, TDS, TH, Na⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, CO₃²⁻, NO₃⁻, and F⁻

|

Primary Data Field Survey

|

33 groundwater sample

|

Spectrophotometric techniques

|

WQI, Piper trilinear diagram, Wilcox diagram, Correlation analysis

|

To investigate hydrogeochemical characteristics and groundwater quality

|

Drinking water and irrigation

|

Pravara River, Maharashtra, India

|

,

Rajendra Zolekar 1

,

Rajendra Zolekar 1

,

Snehal Kasar 1

,

Snehal Kasar 1