Highlights

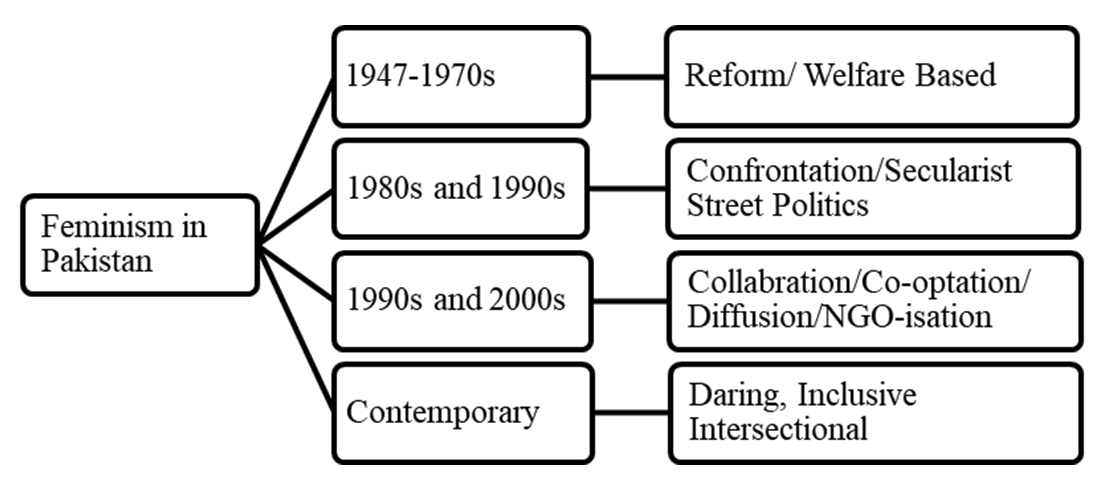

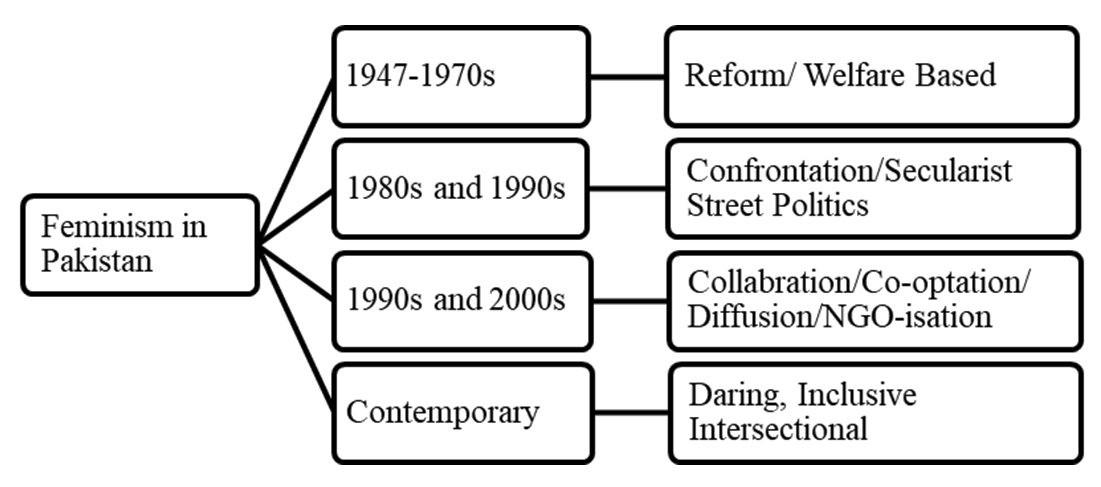

- Feminist movement transformed dramatically since the independence of Pakistan.

- It has evolved with time from reform based feminism to secularist street politics fighting for women’s rights in the mid-1980s.

- During the 1990s and post War on Terror, feminism continued to evolve.

- By the 2nd decade of 21st century, unprecedented flow of information across the world, emergence of strong social media and global events like “#MeToo” movement helped shape the contemporary Pakistani feminism.

- It is now challenging all forms of patriarchy both public and private.

Abstract

This paper is historisization of feminism/feminist movement in Pakistan which has been influenced by national and global rearrangement of power, nationalism, dictatorship, democracy and the War on Terror (WoT). It presents the evolution and transformation of feminism in Pakistan since its inception; also gives an overview of the issues, challenges and achievements of the feminism and how it has evolved to its recent form passing through over seven decades of its journey. It also tries to address the question, where it goes from here, whether the feminist movement expands its scope, or shrivels into little niche pockets of identity-based resistance, is a question for the future. The article heavily relies on desk review of literature produced on feminism in Pakistan. Additionally, a qualitative research was carried out to explore subjectivities, realities, and opinions of women who have been part of feminist movement through in-depth interviews. The second part of in depth interviews included opponents of feminism both men and women belonging to religious right. A purposive and judgement sample was selected keeping in mind the research questions as well as consideration of research resources available. In-depth interviews method of inquiry of Feminist Research Methodology (FRM) was utilised to gain insights and opinions of preselected research participants.

Keywords

Pakistan , History of Feminism , Feminist Movement , Feminism

1 . INTRODUCTION

This article summarizes history of feminism and where it stands in Pakistan today. Feminist movement has transformed dramatically since the independence of Pakistan. It gives an overview of how feminism or feminist movement evolved with time from reform/ welfare based feminism to secularist street politics fighting for women’s rights in the mid-1980s, opposing General Zia’s Islamization project. What shape it took during the 1990s and post War on Terror era, and also its recent outlook. Feminism continued to evolve during seven decades of country’s history and by the 2nd decade of the 21st century, unprecedented flow of information across the world, emergence of strong social media and global events like “#MeToo” movement helped shape the contemporary Pakistani feminism. Contemporary feminism is now challenging all forms of patriarchy and bringing women’s sexuality and body politics to the centre stage of feminist agenda using iconic slogans like “personal is political” and “mera jism, meri marzi” meaning “my body, my choice”.

Feminism or feminist movement remains a contested and controversial concept in Pakistan and is looked upon with suspicion, often maligned as a foreign import and a hobby of elitist women who wish to imitate Western culture while rejecting their own culture, traditions and religion. Opponents of feminism blame this movement to be a Western conspiracy against social, cultural and religious values of an Islamic society. They also say that feminism does not represent all the women and its benefits are limited to urban, educated and elitist women in Pakistan. Unfortunately, feminism is still looked upon with mistrust, a Western conspiracy and faces sever opposition from right wing groups and most Pakistani men. The society in general and men in particular think that feminism is all about hating men and often ridiculed and demonized as “feminazis”- a movement run by few elitist angry women who want to establish their supremacy over men or want to dominate men. The opponents also claim that feminism is not a native phenomenon of Pakistani society and it does not have any ethical and political base. The perceptions about feminism or feminist movement are quite extreme in Pakistan; their demand for equality is often translated into distrust and these perceptions take away the feminist movement’s credibility.

This article also analyses challenges, achievements and gaps left by feminism in Pakistan and details out changes in the nature and content in the feminism in the 1990s and post 9/11 in Pakistan and how secularist and pietist camps emerged. It briefly touches upon global changes in feminist deliberations post War on Terror (WoT). Finally, it reviews the recent form of feminism happening in Pakistan, which has taken up bold and disruptive strategies to challenging patriarchal structures both public and private, raising question of sexuality and doing body politics using slogan, “personal is political” for the first time in the history of feminism in the country. This part of the review also assesses contemporary feminism’s relevance and future in Pakistan. In addition to this, brief overview is given about contemporary issues being taken up by feminism regionally and globally in the 21st century (Saigol, 2016).

History of feminism or women’s movements in Pakistan is as old as the country itself and its footprints can be traced back to pre-partition education reforms and anti-colonialism- nationalist movement. The small steps that Muslim women took in the backdrop of religious and nationalist movements which led to political awareness in Muslim women of India had no rights based agenda. But political activism of women later translated into realization of subjugation and oppression of three generations of Pakistani women to come. Saigol (2016) in her report for Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES) has correctly evaluated, “The latter movements did not have feminist or women’s rights components, but the active participation of large numbers of women in religious or national causes, ultimately led to an awareness of women’s own subjugation and stirred the desire for personal and political emancipation” (Saigol, 2016).

2 . THE AURAT MARCH (WOMEN’S MARCH)

Since 2017, the international women’s day celebrations have taken up a completely different shape: Aurat March (Women’s March) has become a full-fledged women’s movement. It raises questions about structural and private patriarchy, division of labor, women’s subjugation and oppression both in public and private spheres. Since then, every Aurat March in Pakistan is followed by an annual backlash from religious right and conservative segments of the society who reiterate that it is a ‘Western Agenda’.

Aurat March is significant in many ways. First, it is an organic and inclusive event, organized every year by diverse groups of women, men and trans-people from all walks of life, mainly in major cities of Pakistan i.e. Karachi, Lahore, Islamabad and Faisalabad. Second, the March receives unprecedented backlash every from several segments of society including politicians, religious scholars, actors and even some rights activists and veteran feminists. This backlash comes with unusual ferocity because the women hold posters and placards containing slogans of sexual connotations. The critics of the March say that women’s self-expression is vile, immoral and against Pakistani culture, values, traditions and religion. Third, soon after the March, its women organizers started receiving threats of violence, rape and even death. So much so that a parliamentarian of the ruling party urged government to initiate inquiry against the Aurat March organizers to find out who was behind it. Another lawmaker from Sindh filed a complaint against organizers of the Aurat March for promoting vulgarity. The Khyber Pakhtunkh1 assembly went a step ahead and passed unanimous resolution against Aurat March and condemned the “shameless and un-Islamic” slogans, placards and demands of the procession.

Some of the slogans of the March were: “Mera Jism Meri Marzi” (My body my choice), Khana khud garm kerlo (heat up your own food), “Keep your dick pics to you”, “Mein awaara, Mein badchalan” (I loiter, I’m characterless), “Divorced and happy” and “Anything you can do, that I do while bleeding” etc.

The organizers of the Aurat March, feminists, human rights activists and victims of online trolling resolved that a robust and vibrant feminist movement is essential to change the status quo, which is characterized by patriarchy and its performativity, social injustice and inequality, oppression and subjugation of women. The Aurat March is one of the events being organized with different themes since 2017 on 8th March. The purpose behind organizing Aurat March is bringing together intersectional women of Pakistan to raise their voices against inequality, social injustice, oppression and subjugation within the private and public spheres. The March is perceived as the harbinger of the first ever organic feminist movement in the country, which refused to remain silent on various kinds of oppressions faced by women.

Additionally, Aurat March is seeking to provide an alternative to the prevailing liberal feminist discourse by explicitly including questions of class, imperialism, and widespread oppression of the weak by the powerful as “women issues”. Another objective of Aurat March is to set a new feminist agenda and narrative to bring it into mainstream. While describing the Aurat March, feminists were divided into liberal progressive and socialist feminists– though both factions agreed that body politics is the need of the time, and it is essential for furthering women’s issues that affect them both in public and private spheres.

3 . RATIONALE AND METHODOLOGY

The post Aurat March backlash from almost all quarters of the society urged me to evaluate feminism in terms of its challenges, achievements, silences and future and to find out why this remains a contested and dangerous concept in Pakistan. This article heavily relies on the literature mapping which is produced by Pakistani feminists, several books and academic/journal articles were reviewed for strengthening the discussion and findings of this research. Additionally, a qualitative research was carried out to explore subjectivities, realities, and opinions of women who have been part of feminist movement through in-depth interviews. The second part of in depth interviews included opponents of feminism both men and women belonging to religious right. A purposive and judgment sample was selected keeping in mind the research questions as well as consideration of research resources available. In-depth interviews method of inquiry of Feminist Research Methodology (FRM) was utilized to gain insights and opinions of preselected research participants. Being part of Women Action Forum and feminist movement for over two decades, I was able to connect to veteran feminists, young contemporary feminists. About 10 in-depth interviews (IDIs) were conducted with veteran feminists; among them two were founding members of Women Action Forum (WAF) and young feminists and organizers of Aurat March. Similar number of IDIs was conducted with preselected research participants from religious right.

4 . DISCUSSIONS

4.1 Reform and Welfare Based Feminism: 1947-1970s

In 1940, Mr. Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan announced2, “Women are supposed to create a sense of general political consciousness. They should stand shoulder to shoulder with men in practical politics”. Women’s political activism for independence removed cultural, social and religious barriers of mobility for attending political processions and rallies. Gaining confidence from their experience of political participation in the freedom movement, women started to engage with newly emerged state for their political and legal rights. With the abrupt demise of Quaid e Azam3 in 1948, women’s temporary political activism halted but few determined women like Fatima Jinnah4, Begum Raana Liaquat Ali Khan5, Begum Fida Hussain, Begum Shaista Ikram Ullah and Begum Jahan Ara Shahnawaz6 continued their efforts for political empowerment of Pakistani women. Mummtaz (2005) in her article observes, “It was possible, from the early years of the twentieth century, for women to demand the rights to education; to agitate for the right to inheritance and end to polygamy and to lobby for voting rights as the struggle for independence got momentum. The campaign for Pakistani autonomy gained pace in 1946-47, demanding a separate state for Muslims in the Indian subcontinent. The movement saw mass mobilization of Muslim women who had never stepped out of their homes”. In the postcolonial state, women mentioned above belonged to ruling elite who strived for inclusion of women in the political process but faced strong opposition from clergy. Saigol (2016) in her report enunciated, “In the early period of Pakistan’s history, the struggle for women’s rights was piecemeal, gradual and evolutionary. Progressive legislation was often resisted by the clergy, which perceived the steps in the direction of women’s rights as western and antithetical to religion and culture. Nonetheless, women belonging to ruling families continued to struggle for inclusion in the political process and rights”.

Although women’s struggle for equal political and legal rights was spearheaded by the women from ruling elite, it made little headway in demanding their equal rights through legislature. The early years of women’s movement remained devoid of their equal rights, body politics or politics of resistance; it was literally impossible for women to raise such questions with the advent of Brelvi7 and Deobandi Ulema8 as stakeholders in the state system. Ulema had clear vision of the new state where Muslims could live their lives according to majority religion without fear of persecution. The secular views of Quaid e Azam and Liaquat Ali Khan9 were discarded soon after their demise. Mulana Maududi, a stark opponent of Muhammad Ali Jinnah and separate state for Muslims migrated to Pakistan in 1947, established his political party to push the agenda of political Islam, arguing that the state should be guardian of Islam and Pakistan must be ruled in the light of Quran and Sunnah. The Ulema held several conventions and passed several resolutions that Islamic Law should be incorporated into the constitution of Pakistan. Maududi advocated for barring women from holding any public office, proposed a separate assembly for women and reasoned that the voting rights should be granted to all Muslim adult males but not to all women. Instead only ‘educated’ women should be entitled to vote. However, the agenda of right wing political parties and Ulemas’ vision of Pakistan was never taken seriously by the government from the very beginning. Mumtaz and Shaheed (1987) have articulated, “Jinnah’s vision of non-theocratic Pakistan, and Liaquat’s aspiration for building a liberal, democratic political system, were not viewed by political elite as being antagonistic or contrary to Islam……it is true that in the early years of Pakistan’s life, the orthodoxy was looked upon with disdain and irreverence by political leadership, it is equally true that measures to pacify them were also taken. These were exemplified by the concessions made to the Moulvis (clerics). For instance, Pakistan was declared Islamic Republic of Pakistan under the 1956 constitution and Ulema were provided with advisory role in legislature” (Mumtaz and Shaheed, 1987).

The ruling elite, during the early years of Pakistan was educated and found no time to investigate and philosophically rationalize “common” Islam for all or they thought it unnecessary. However, the ruling elite had always remained defensive about being pronounced “un-Islamic” by Ulema and gave into the hegemony and blackmailing of Ulema. Ultimately, government(s) became hostage at the hands of clergy and could not break their stronghold till today. Women and their relation with state and society were regulated by the religious, cultural and societal norms and practices. Rouse (2006) in her book, “Gender, Nation, State in Pakistan: Shifting Body Politics”, noted that “By and large the policy in the early period was one of the “benign neglect” whereby gender relations continued to be governed and ruled by social custom and practice, inevitably affected by the economic and political policies of the state” (Rouse, 2006). Nonetheless women (from ruling elite and religious parties) in the early years of Pakistan were able to achieve some concessions from the state. They worked with great zeal but in an “acceptable” Islamic and cultural framework i.e. nurturing and caring role- for refugees’ rehabilitation and resettlement immediately after the partition. Ms. Fatima Jinnah established Women’s Relief Committee and several other such committees/organizations were also created and run by women.

Soon after the independence two aspirant women, Begum Shaista Ikram Ullah and Begum Jahan Ara Shanawaz reached to first constituent assembly as members and contributed to important legislations regarding political and legal rights such as inheritance and family laws and polygamy etc. With the efforts of these two phenomenal women, Pakistani women achieved dual voting rights which were later abolished by General Ayub Khan10. Later Ms. Fatima Jinnah was nominated as the presidential candidate of combined opposition parties. “By agreeing to challenge Field Marshal Ayub Khan at the height of his dictatorial power, she did not only electrify the nation, but also took a massive step towards the political empowerment of women” (Shami, 2013). Till 1960s, women recognized their demands for legal rights, the educated and politically aware women managed to safeguard legal rights for them and their fellow women in the country through Muslim Family Laws Ordinance (MFLO) 1961. The MFLO is debated by scholars whether it had equitable benefits for all the women of Pakistan or it benefitted privileged class women as well as its appropriateness concerning violation of provisions made. Rouse (1988) in her article, “Women’s Movement in Pakistan: State, Class, Gender”, writes, “Women attained voting rights, and the Family Laws Ordinance was passed in 1961. Under this law, women were officially able to inherit agricultural property (in consonance with Islamic law), second marriages were made contingent upon agreement by the first wife, divorce was made more difficult for the male, women attained the right to initiate divorce for the first time, and a system of registration of marriages was also introduced (Rouse, 1988).

General Ayub Khan’s dictatorial regime ended with massive countrywide protests and constitution was once again abrogated by General Yahya Khan11 who imposed martial in the country in 1969. General elections were held under Yahya Khan in which Awami League12 won the elections convincingly but Yahya Khan was unable to transfer power to Mujib Ur Rhman13; instead military operation was launched in East Pakistan which ended in 1971 resulting in cessation of East Pakistan and creation of new country Bangladesh. Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) gained popular majority in the 1970 elections in the West Pakistan and Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto14 assumed power in 1972. It is believed that women in Pakistan voted independently without any pressure from their men as educated women belonging to People’s Party led an effective campaign for Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s popular politics of equality and freedom from oppression. Two phenomenal women, Naseem Jahan and Begum Ashraf Abasi15 were tasked by Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto in 1973 to give their inputs in drafting the new constitution and as result of their efforts, women gained status of equal citizens. “The 1973 Constitution gave more rights to women than any previous constitution in the past. Article 25 of rights declared that every citizen was equal before law and Article 25 (2) said there would be no discrimination based on sex. Article 27 of fundamental rights stated that there would be no discrimination on the basis of race, religion, caste or sex for appointment in the service of Pakistan. Article 32 of the basic principles of state policy guaranteed reservation of seats for women, and article 35 stipulated that the state shall protect marriage, family and mother and child”, quoted Saigol in her account of Women’s Movements in Pakistan” (Saigol, 2016). The Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) government took concrete steps for women’s social, political and economic emancipation. Moreover, several organizations like Commission on Women and Women’s Institute, Shirkatgah, Aurat Foundation, Women Front and many other women organizations in smaller cities of Pakistan were created, the members (educated and professional) of these organizations played pivotal role in creating vibrant women’s movement in Pakistan in the years to come. However, the period of General Zia Ul Haq’s16 dictatorship disrupted vibrant political activism of women; lots of women politicians had to flee the country. After the promulgation of Hudood Ordinances by General Zia, this void was filled by urban, educated, middle class women of Women Action Forum (WAF).

Having said that, during the early years of Pakistan, there was no organized and active women’s movement, these headways were made due to the efforts of the women of ruling elite, while remaining within the religious and cultural framework. These women did not take up body politics, women’s subjugation or economic empowerment as political stance; rather they reconciled with the accepted gender roles as well as religious and cultural norms. “At this early stage of the country’s history there was no coherent and organized women’s movement to challenge the measures by the religious lobby and the clergy” (Saigol, 2016). The absence of feminist movement during the early years of Pakistan manifested in lack of support for Ms. Fatima Jinnah by women like Rana Liaquat Ali Khan and Begum Fida Hussain. Ironically, Jamaat e Islami17 women supported Ms. Fatima Jinnah against General Ayub Khan for their political gains but later Benazir Bhutto18 was opposed by them on the ground that a woman cannot be the head of the state in an Islamic country. From the early years of Pakistan and till the coup of General Zia, state and women’s movement remained collaborative partners. Women’s movement in those times was devoid of conflict, confrontation and resistance. Both civil and military governments supported women’s organizations as long as they continued to perform welfare and traditional gender roles under acceptable social and religious norms.

In conclusion, the issues faced by the 1st generation of feminism in Pakistan were: first, there was no vibrant and organized women’s movement present in the early years of Pakistan to challenge increasing influence of clergy in the state’s affairs. Second, whatever was done due to the efforts of women from ruling elite, professional and educated women, the benefits of these achievements remained limited in scope. Third, attempts made by women and concessions granted by the successive governments strictly remained within the confinement of the religious- cultural- gender ideology framework. Fourth, the first generation feminism was all but compliance and collaboration with the state and the state played patronizing role. And finally, there was no space for body politics but complacency and political expediency on part of both parties.

4.2 Confrontation/Secularist Street Politics: 1980s

The 2nd generation of feminist movement commenced in the backdrop of promulgation of Hudood Ordinances and implementation of Islamization project by General Zia. To understand fully what prompted Pakistani women to agitate against military rule, it would be pertinent to review the political scene of the country.

Pakistan National Alliance, right wing political alliance initiated anti Bhutto movement which resulted in his arrest in 1977. General Zia ul Haq imposed martial law and in his speech to the nation, he stated that it was imposed to avert national crisis and promised to hold general elections within 90 days. No one predicted Zia’s intentions till Mr. Bhutto’s release and consequent overwhelming public support for him in Lahore and Karachi, which led to re-arrest of Mr. Bhutto and postponement of general elections previously promised by Zia. Later he announced his intentions of establishing an Islamic state. Khan (2006) in her book “Zina, Transnational Feminism and Moral Regulation of Pakistan Women” enunciates, “The Pakistani Constitutions of 1962 and 1973 called for appointment of Council of Islamic Ideology to bring existing laws into conformity with Islam. The military regime of General Zia-ul-Haq (1977-1988) took this mandate more seriously than had any of his predecessors and in 1979 promulgated the Hudood Ordinances as a first step towards the process of Islamization (Khan, 2006).

It will be simplistic to evaluate that Islamization of Pakistan began under Zia’s rule. Pakistan had always been faced with contradictions from its inception; it was the aspiration of the founding fathers to create a separate “Muslim Country” where people could live according to the principles of Islam. It goes without saying that there had been unremitting tension between the modernist forefathers and the clergy since the beginning, during the 1960s and 70s and it still exists. The successive governments- either owing to their own will or pressure form the clergy took several steps that led to make Pakistan the “Islamic Republic”. “It seems problematic to suggest an absolute opposition between Pakistan prior to and post 1977 when Zia came to power, emasculated his political opposition, and amended the constitution to reflect and adhere to what he and his supporters proclaimed as “Islamization” policies designed to bring the country more “inline” with its historical intent” (Rouse, 2006).

However, after seizing power General Zia furthered socialist Islamic agenda initiated by Bhutto into Islamization of Pakistan. General Zia intended to Islamize Pakistan on Deobandi (Whahabi)19 Islam; the Saudi Arabia and Jamaat e Islami version of Islam. Zia used two-pronged strategy to Islamize the country. One, he brought several changes in the public sphere for instance, in the school curriculum, judiciary, media, number of policies were introduced to cleanse society of Un-Islamic practices and imposed strict sanctions on freedom of speech and expression. Surprisingly, he did not try to overhaul the economy which depended heavily on international funding, due to the cold war between the United States of America (USA) and Russia. However, several changes in the banking system were made and Zakat20 and Ushr21 were introduced. Second, in order to implement his Islamization project, he tried to restructure private sphere creating Slaat committees, observed through vigilantes that people are living their personal lives in conjunction with Islam. Moreover, the significance of Chadar (veil) and Chardiwari (four walls) exemplified. The onus of projection of piety -women being repositories of religion and culture- fell wholly upon women. The entire legal system was tempered, which proved detrimental for women and minorities. Zia (2018) in her book “Faith and Feminism: Religious Agency or Secular Autonomy” observes that “Caught in the midst of a state campaign of Islamization in the1980s led by military dictator General Zia ul Haq (1977-88), Pakistani women bore the harshest brunt and backlash of a religio-military dictatorship” (Zia, 2018).

The unprecedented discriminatory legislation was faced by Pakistanis minorities, women and poor women particularly under the Islamization project of General Zia. Hudood Ordinances include; Zina22 ordinance, Law of theft, Consummation of alcohol and Qazf23. The Hudood Ordinances have provisions for severe punishments, such as stoning to death, amputation of hands and feet for theft, flogging in public and are equally applicable for minorities. Khan (2006) explains Zina Ordinance, “The Zina ordinance censures “illicit sex” and prescribes predetermined punishment for the offenders based on particular Sura chapter 24 verse 2 of the Qur’an: “the woman and the man. Guilty of fornication. Flog each of them. With a hundred strips”…. Fornication and adultery became non-compoundable, non-bailable, punishable by death. A non-compoundable offence is one that the police or the government may continue to investigate and prosecute even if the original complainant withdraws his or her statement implicating the accused” (Khan, 2006). Moreover, it makes no distinction between adultery and rape as well as it excludes evidence of women and religious minorities. Additionally the burden of proof was also laid upon the victim, “the witness for zina bil jabr24 should be at least four Muslim adult males about whom the court is satisfied, having regard to the requirements of tazkiya-al-shahood (self-credibility of a witness), that they are truthful persons and abstain from major sins (kabir), give eye witness of the act of penetration necessary to the offence” (AHRC, 2004). Moreover, the evidence of women and minorities were rendered half of that Muslim men.

In 1981, a group of women held meeting in Shirkatgah25 and established Women Action Forum (WAF), followed by its chapters in Karachi, Islamabad and Peshawar. WAF resisted Zia’s Islamization project on two fronts; one against discriminatory laws promulgated by the government and second, segregation of women in the public arena, education, media, dress code etc. WAF, an alliance of individual women and organizations remains an important marker in the history of feminism in Pakistan. Women Action Forum adopted confrontational and resistive street politics, they demonstrated to challenge the laws and other discriminations against women imposed in the name of Islam. As a strategy, WAF distanced itself from affiliation with any political party, or any other professional associations at that time to preserve its distinct autonomous character and fought forcefully against the Martial Law. WAF played phenomenal role in making women’s rights as public discourse. WAF’s efforts for prodemocracy, anti Hudood laws agitation and later lobbying with parliamentarians, led every political party to put women’s rights agenda on their manifestos including Jamaat e Islami. Without going much into details of achievements of WAF (documented already in volumes), it is pertinent to highlight challenges and criticism they faced as well as their strategies to counter it.

1) WAF, a group of women and the organization took no clear position on religion, several founding members had secular view but they accommodated all members having varying beliefs and sentiments about religion. “WAF is often criticized for using progressive religious theoretical framework. In its initial years, as the organization that spearheaded the prodemocracy movement against military dictator and his imposition of Islamic law, WAF decided to employ the strategy of using progressive interpretation of Islam to counter patriarchal state religion. They succeeded to some extent and even got the unlikely support from right wing Islamic groups and parties” (Zia, 2018). WAF counter this objection by reiterating that military regime was trying to superimpose a specific version of Islam upon all sects of Islam, therefore, it was important to seek support and mass mobilization for opposing specific brand of religion. 2) They argue that the Western secularism is the result of continuous struggle spanning over centuries, it was not achieved overnight. “In postcolonial states like Pakistan a modern secular democratic state had to be constructed from the scratch. Another conundrum for the women’s movement was that while feminism is premised on the idea of personal is political; secularism separates the personal from the political because it separates the private from the public” (Saigol, 2016). To them, the idea of secularism and feminism were mutually contrasting. However, after long internal debate, 1990s was the time of WAF’s departure from liberal feminism to secular feminism. WAF reiterated reversion of original secular form of the constitution and employed lobbying strategies with the court and legislature for bringing changes through legislation and policies. This was the time when women’s movement lost its steam; this change was called co-option/collaboration by Saigol (2016).

Major critique on Women Action Forum remains, 1) WAF’s status of non-political organization, 2) using theocratic framework and 3) a movement inspired by western feminism a ‘western import’, exclusivist, led by upper class educated, urban women lacking grassroots connection. Many questions are raised about its being non-political organization as well using progressive religious framework during the early years of the movement. Whether it was political expediency, complicity or compromise?

Answering the first criticism, Saigol (2016) illustrated in detail in her report for FES, that there had been a heated debate between Lahore and Karachi chapters whether they should join hands with Movement for Restoration of Democracy (MRD) or stay as a non-political organization. Karachi chapter was already creating linkages with People’s Party, other ethnic groups and trying to address larger political issues considering that women’s issues cannot be resolved in vacuum. However, the Lahore chapter was of the view that WAF should focus on the women’s issues and anticipated that women’s issues would subsume in the larger issues.

“I would argue that it is essential that women retain an independent organization so that their cause does not become subservient to other issues. While retaining their relative autonomy, however women can and also should enter into a principled alliance with the other political groups and parties whose struggles are not in contradiction to theirs. By forming such alliances, women can put women’s question on the agenda of other political formations” (Rouse, 1984)

Thus, the debate concluded when WAF declared that “all issues including democracy and federalism are women’s issues as they have an impact on their lives. WAF subsequently challenged all forms of discrimination whether based on sex, gender, class, caste, religion or ethnicity” (Saigol, 2016).

WAF members have explained in volumes of academic documents as to why they chose the progressive religious framework. Khan and Kirmani (2018) enunciated, “WAF maintained a publicly ambiguous position vis-à-vis its position on religion out of political necessity throughout the 1980s. However, they largely chose to work within a universalistic rights-based framework. Hina Jilani, prominent human rights lawyer and WAF member, explained this choice, arguing that engaging with Islam was thought to be futile for activists as Islam contains many schools of thought, and it would inevitably be the school favoured by the government that would dominate. Similarly, Saigol (2016) said that many activists by the late 1980s realised that they would never win if they played on the ‘mullah’s26 wicket’, that is, by the rules set by conservative religious groups and leaders Khan and Kirmani (2018).

This has also been critically analyzed by Zia (2018) “WAF’s working within the framework of religion has not only been successful but has also subsumed all other forms of feminist expression…. Inclusive approach of the women’s movement on the issue of religion has enabled and assisted the political expressions of Islamic Feminism” (Zia, 2018). In fact, ambivalence of secularist women’s movement about using universal human rights framework or religious framework made it more inclusive and gave rise to identity politics in Pakistan and resultantly created a new brand of feminism ‘Islamic Feminism’ without undermining right wing women’s agency. Jamal (2013) in her book ‘Jamaat e Islami Women’ argues in detail that “Jamaat Islami women’s productive use of their social class and cultural location enables them to challenge the dominance of liberal/secular social and political groups and to claim the leadership of working class rural and urban women.

The opponents of women’s movement -often from right wing-blamed WAF that it imitated western feminism, towed foreign agenda, was educated, urban middle class women’s club, and excluded women of other subjectivities. Shaheed (2005) cites, “The deliberately promoted myth that women who engage in struggles for women’s rights are ipso facto, westernized and alien to their own societies ought to be robustly contested….. the absence of vernacular terms facilitates the suggestion- that ‘feminism’ is a North American/ European agenda, if not an outright conspiracy, and its local ’westernized’ proponents, at best, out of touch with the grounded reality of ‘local women’ and representatives of their needs and at worst they are agents of imperial agendas (Shaheed, 2005). Members of WAF thought it unnecessary to pay attention to such allegations and vilification by certain groups rather they felt it more important to keep on working, researching and producing knowledge which brought vital changes in the socio-political and economic lives. Ayesha Khan in an interview at the launch of her book ‘The Women’s Movement in Pakistan: Activism, Islam and Democracy’ says, “There’s no nebulous grass-roots out there that you can mobilize and that you should be a part of in order to be authentic- there will be women in different parts of Pakistan who mobilize for their own interests. WAF women mobilized for their own interests but they also mobilized for the broader interests of citizens including non-Muslim minorities as well as women from different walks of life who were directly impacted.”

WAF, despite being criticized for belonging to upper class, educated, urban exclusivist women’s movement, it created linkages across classes, networks, associations, trade unions, Sindhiani Tehreek (which was more vocal in agitating social, political and religious structures than WAF) and most recently peasant women movement in Okara, Lady Health Workers’ (LHWs) movement, Federally Administrated Tribal Areas (FATA) tribal women association and Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM).

The 2nd generation of feminism in Pakistan would be incomplete without discussing Sindhiani Tehreek (ST) and right wing women activism in the 1990s. During General Zia’s era, WAF was in the forefront of women’s movement, but there was a vibrant women’s movement in Sindh which was much bolder than WAF and the issues they took up were more intrepid than their counterparts. They fearlessly stood against patriarchy and dictatorship. Saigol (2016) highlights their agenda points as: “1) Sindhi nationalism and provincial autonomy, 2) social class distinctions and conflict, 3) patriarchy and the subordination of women, and 4) the struggle for democracy. From the very beginning, Sindhiani Tehreek was decisive about their personal and political demands; they raised their voice for restoration of democracy and at the same time against the harmful customs and practices prevalent in Sind such as Karo Kari (Honour Killing), marriage to Quran27 (giving up their right to property for male members of the family). ST raised the issues of women’s share in property, polygamy, the right to marry and sought an end to cultural and customary practices and norms that discriminate against women. Sindhiani Tehreek struggled against Waderas (feudal lords) and demanded the distribution of land to Haris (peasants). Apart from political and structural issues, ST also raised community issues such as the provision of electricity, roads and medical facilities for children. by day or night in buses, vans and wagons, ST women would cover long distances for mass mobilization” (Saigol, 2016). Sindhiani Tehreek was remarkable because of its bravery of taking up direct action against patriarchy, sexuality and ‘Waderashahi’ (feudal supremacy) as well as greater issue of restoring democracy. It is only criticized for overt emphasis on Sindhi nationalism.

“Women in Pakistan have been viewed, by political actors, the state, and more broadly as well, as either ‘secular/feminist/godless/Westernised’ or ‘authentic/Islamic/traditional”. However, the secular/religious distinction has evolved and has been reinforced in recent decades following the growth of Islamist movements worldwide and in Pakistan- in particular since the 1980s and following the global war on terror post 9/11” write Khan and Kirmani (2018) in their article “ Moving Beyond Binary: Gender based Activism in Pakistan. Women of right wing parties have their women wings and were more organized than any parties. During the Islamization project by Zia, large number of right wing parties’ members was made part of the Shura28 including women and had state favor. Islamist women had love-hate relationship with Zia’s rule; they complied with certain policies and opposed a few. They briefly joined hands with WAF against Hudood ordinances, but at the same time they aspired to translate and achieve women’s rights within the framework of religion.

4.3 Collaboration/Co-optation/Diffusion/NGO-isation: 1990s and early 2000s

Later in 1990s, with the advent of NGOs in Pakistan, funded activism diffused women’s movement. Several middle class feminists established their own organizations and towed the agenda of the international nongovernmental organizations; gender and development, gender sensitization, gender mainstreaming were the new buzzwords that replaced the word women. This replaced struggle of challenging and changing social structures (patriarchy) through resistance. Veteran feminists like Rubina Saigol, Saba Gul Khattak and Dr. Farzana Bari have discussed and analyzed feminist movement’s transformations during 1990s several articles and reports. To them, the movement which was robust and vibrant during the 1980s reached to a saturation point, diffused and became stalled in the 1990s and till early 2000s with the arrival of NGOs and funded activism Pakistan. They also think that co-optation of the movement also directed the movement to bend with policies of respective governments had lost its spirit of fighting for equal rights of women.

Rubina Saigol expresses “welfare and service delivery organizations are generally believed to be neither rights based nor feminist in orientation, movements such as Sindiani Tehreek which espouses feminist principles exist in small pockets”. She also thinks that “the founding members of the movement have failed to mentor or aspire young women of second and third generation of passionate commitment witnessed in the earlier decades”. She emphasizes that “movements are made up of passion, commitment and volunteerism not salaried 9-5 project. These projects seldom address structural injustices and patriarchy because it is unacceptable for governments’ and face retaliation by the state. Moreover, the movement diluted due to work of NGOs it was limited to political activism only” (Saigol, 2016). Saba Gul Khattak and Dr. Farzana Bari also articulated in their paper “Power Configurations in Public and Private Arena: The Women’s Movement’s Response”, “there were subtle changes in the manner in which women’s issues are conceptualized and the work done by NGOs cannot be called feminist or women’s movement. The funded movement is not and autonomous movement either financially or in terms of agendas and ideology. Whenever there is threat to structures and patriarchy the governments are not amenable to change, moreover global changes has depoliticized and weakened the movement”. In their article, they say, “it stayed aloof from issues that revolved around cultural construct or addressing issues considered to belong to private spheres, such as family, marital rape or domestic violence….. The movement cannot claim substantial success, especially when it comes to family and community” (Bari and Khattak, 2001).

Nonetheless, through activism as well as lobbying, influencing policy and practice as well as putting women’s rights on the national agenda was a commendable achievement of the movement. Naming few gains in legislative reforms during the last decade, many pro-women laws were passed by the Parliament such as Women Protection Act, Honour Killings Bill, legislation against acid attacks and other harmful practices and most importantly securing increased number of seats in the parliament and local governments. However, some feminists are of the view that the movement was diffused and de-politicized due to funded activism (NGO-isation) and co-optation with governments over time and yet fragmented.

Alhuda29 phenomenon appeared in 1990s; an Islamic school for women was created by Farhat Hashmi in 1994 in Islamabad and the network is grown into 70s urban locations in Pakistan. The curriculum at Alhuda schools is a mix of old and modern education attracting upper (elite) and middle class urban educated Pakistani women and also diaspora in North America, Canada, Europe, Middle East and East Asia. Farhat Hashmi rejects the customary practices prevalent in the society. Although she distanced herself from Jamaat e Islami politics, “Yet that early involvement clearly helped shape her conviction that individual disciplining and righteous lifestyles are the first step towards social reform” (Mushtaq, 2010). Farhat Hashmi has created a large network of schools to preach moderate Islam. She has been criticized by Ulema vehemently, as they have given Fatwas against her for maligning original sacred scripts of Islam and urged the government to try her for treason. Although she faced blatant opposition from Ulema, large number of women follow her as their role model while others criticize her exclusive women’s club and sugar coated reformist agenda. Alhuda cannot be called a movement but perhaps a fad or a fashion in the wake of availability of Saudi funding in 1980s and identity politics which started after 1990s.

In conclusion, women’s movement in Pakistan evolved, transformed and progressed since the creation of Pakistan in many different forms and in different directions. Nonetheless, it significantly, through activism as well as lobbying and community mobilization, influenced policy and practice viz a viz putting women’s rights on the national agenda. Naming few gains in legislative reforms during the last decade, many pro-women laws were passed by the Parliament such as Women Protection Act, Honour Killings Bill, legislation against acid attacks and other harmful practices etc. and most importantly securing increased number of seats in the parliament and local governments. The religious institutions within the state machinery like Federal Shariat30 Court and Council of Islamic Ideology opposed some provisions of Women Protection Act. Council of Islamic Ideology (CII) also shot down the use of DNA testing in rape cases, opposed government’s stance over child marriages and on women’s right to object to husband’s second marriage. Moreover, domestic violence bill 2009 is still pending because of the opposition from right wing parties.

Moreover, the 2nd generation of feminism failed to meaningfully challenge and address several pertinent issues related to patriarchy and subjugation of women, family, heterosexuality and sexuality. Rights of lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transgender people were not addressed- although these are taken up by contemporary feminists globally. Saigol (2016) in the concluding section of her report goes on to say “The most important silence is about family and sexuality, the mainstay of patriarchy and women’s subjugation…. But refrained from touching issues of sexuality, especially Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals and Transgender. Questioning the family comes too close to home and seems to make women uncomfortable as they would then have to deal with representatives of patriarchy at home” (Saigol, 2016).

4.4 Year 2001 and beyond: Contemporary Feminism in Pakistan

“A feminist movement can only succeed when it mirrors the makeup of the women and the society for whom it operates” (Shah, 2014).

In an article published in the New York Times, writer Bina Shah argues that, “Many Pakistani men and women believe that women’s rights need to go no further than improvements Islam brought to the status of women in tribal Arabia in the seventh century. Men in Pakistan are not yet ready to give up their male privileges, and many Pakistani women, not wanting to rock the boat, agree with them.” The Pakistani historian Ayesha Jalal calls this the “convenience of subservience” when elite and upper-class women marginalize women’s movements in order to maintain their own privilege” (Shah, 2014).

Feminism in Pakistan has gone under several shifts, from legal reforms to secular rights based activism to Islamic feminism to post-secular feminism. The 3rd generation of feminism in Pakistan is influenced by the major global event of 9/11 and subsequent War on Terror (WoT) in two different ways. Both Secular and Islamic feminism were impacted by these events and devised new strategies and developed standpoints relevant to their time and space. Considerable literature has been produced in the world as a result of WoT. Zia (2018) in her book, ‘Faith and Feminism’, elucidates, “The last and most recent wave may be seen in a body of post 9/11 scholarship that is critical of enlightenment ideals, modernity and secularism, and is invested in uncovering the ‘complex subjectivities of Islamists’. Predominantly produced by diasporic anthropologists, the politics of this body of work has post-secular and postfeminist bent” (Zia, 2018). This has opened avenues for finding possibilities for Islamic feminism in Pakistan. Zia calls it retro- Islamic scholarship because she thinks this is different from the modernist Islamic scholarship developed back in the 1990s. Saba Mehmood thinks that this scholarship created agency in Muslim women, though their demands are docile but their agency and progress should be examined in contrast to Western feminist goals and struggles. This scholarship enabled Muslim women to do identity politics based on religion. Zia reiterates, “Distinct from the earlier modernist and/or secular feminist task mentioned above, the current retrospective scholarship on Islamist women seeks to reconstruct narrowly defined religious identities by delegitimising the alternative strands of non-faith-based identities as, colonial legacies or Western imports” (Zia, 2018). The contribution of recent form of Islamic feminism is hidden or investigations into their agency, progress and contribution towards women’s overall are not made. Moreover, Afiya S. Zia adds that no Islamic feminist movement exists in Pakistan. 9/11 and WoT did not only affect the Muslim world to rethink their identity on the basis of faith and culture but identity crisis also sprung up globally. Zia also calls it retro- anthropological project, whose fruition is yet to be unfolded.

As stated above, there have been two opposing strands of feminism present in Pakistan i.e. secular and Islamist. The binary always existed and still exists, and this binary has provided both strands opportunities to grow, reflect and act. For instance, Islamic modernist feminism back in the 1990s was influenced by secular feminism’s insights. The liberal secularist feminism has contributed to women’s question in the past, present and it has bright future in Pakistan. Recent vibrant wave of feminism in Pakistan is an extension of the feminism started by the 2nd generation of feminism. The overwhelming masculinization of state and public spaces as well as overt Islamization, Talbanization and post WoT impacted secular/ liberal women’s movement vehemently. Their response towards these occurrences was also strident. Rouse (2006) says, “The most crucial shift, in my view, for women has come about not through the state policies and practices, but as a result of the militarization and progressively masculinization of the society itself”.

Masculinized spaces and militarization of society have overarching impacts on women’s lives, their mobility is restricted and safety is in danger as well as their socio- political and economic activities are hampered, and their scarce livelihoods are further condensed. This leads to increased violence in both public and private spheres. Zia (2018) gives example of movement of LHWs, polio and community workers, who despite all odds stood firm and resisted clergy and militarization furiously. She quotes Bushra Arain’s interviews with polio vaccinators in 2013, “This is a mockery and false pretense. It is an attempt to grab the moral ground and worth of our practical contributions towards vaccinating Pakistani children against all diseases. Why should we allow these clergymen to become the false faces of such an important job? They are simply doing so for political mileage” (Zia, 2018).

Women’s movement in Pakistan today is passing through the most stirring moments. Feminist events that took place in the last couple of years are the new history in writing. Saigol (2019) in her article in the Daily Dawn says, “Aurat March 2019 was one of the most exciting feminist events in recent years. Its sheer scale, magnitude, diversity and inclusivity were unprecedented. Women belonging to different social classes, regions, religions, ethnicities and sects came together on a common platform to protest the multiple patriarchies that control, limit and constrain their self-expression and basic rights. From home-based workers to teachers, from transgender to queer- all protested in their unique and innovative ways. Men and boys in tow, carrying supportive placards, and the marchers reflected unity within diversity, seldom seen in Pakistan’s polarized and divisive social landscape” (Saigol, 2019).

The Aurat March 2019 took the entire country by surprise, followed by scathing criticism on the bold slogans written on the placards. The extent of frenzy created by these slogans reaffirms that it shook the very foundations of patriarchy. Saigol explains in the same article, “Aurat March 2019 also marks a tectonic shift from the previous articulations of feminism in Pakistan….While the past expressions of feminism laid the foundation for what we see today, the radical shift of feminist politics from a focus on the public sphere to the private one -from the state and the society to home and family- manifests nothing short of a revolutionary impulse. Feminism in Pakistan has come of age as it unabashedly asserts that the ‘personal is political’ and that the patriarchal divide between the public and the private is ultimately false” (Saigol, 2019).

Different forms of feminism, if contextualized historically, picked up issues specific to particular era in the history of Pakistan. Body politics was not picked up by WAF even when the state was doing politics on women’s body. Saigol (2019) recaps in her article, “The state was consistently referring to sexuality (for example, in laws on fornication), the veil and the four walls of the house- all designed to control the rebellious and potentially dangerous female body capable of irredeemable transgression”. The 3rd generation of feminism is daring, more inclusive of all classes, ethnicities, genders, religions and cultures; is free from previous prejudices. There are no leaders and no followers in the movement. Apparently, it comes naturally to the new generation of feminists in Pakistan to be bolder and more pluralistic and position them in accordance with the changing world. The 3rd generation feminists have used disruptive strategy and openly talked about body, family and sexuality issues- hitherto untouched in Pakistan.

That is why Aurat March 2019 also attracted unprecedented reactions (violent, abusive, and threatening) in condemnation as well as in its support. This testifies the pertinence of issues taken up and it is hoped that the fresh blood will continue to bear the torch of resistance and agitation, passed on by their predecessors.

4.5 Feminist Movement in Pakistan: Conversation with Leading Feminists

Feminists and women’s rights activists interviewed for this research, unanimously called feminism a full-fledged socio-political movement. They thought that the achievements of feminist movement in Pakistan are numerous. Whatever social, political and economic emancipation women have achieved since the inception of Pakistan is mostly attributable to the untiring efforts of feminists who kept struggling to put the women’s agenda at the centre stage. The challenges, opposition all sorts of allegations faced by the movement had failed to shake their resolve to bring change in the lives of women of Pakistan. Following are views shared by feminists both veteran and young, about what they think of feminism.

Ismat Shahjahan a leading socialist feminist and General Secretary of Awami Workers Party says;

“We theorize feminism as the only political struggle which challenges the state as well as immediate relations in the family. Feminism is the only political movement which aspires to change society at large as well as immediate family relations. No other political movement does that. Feminism does not only talk about state and economy but it also challenges immediate relations both public and private – both at home and work place.”

Ismat Shahjahan refutes feminist movement being a foreign import in the following words;

“People usually dismiss feminism as imported ideology, which contradicts with Pakistani traditions, values and culture. But as feminists, we ask if feminism is western, what is indigenous? Even the religion came from Saudi Arabia, democracy is western invention, and Carl Marx was not born in Pakistan. When women start working for their rights, they eventually become conscious of feminism, whether they belong to East or the West. When it comes to active politics, the right wing in Pakistan always sides with the elite. Their argument that feminism is foreign, westernized, elitist, and exclusive is hypocritical. They simply hide behind class, tradition, culture and religion.”

Similar views were expressed by Dr. Farzana Bari and academician and renowned feminist;

“Feminist consciousness comes from within. Whether it was the Western theory or not, women of all sections of society demand equality on the basis of their experiences. If a woman is facing violence and thinks that it is not fair and that she should not be beaten up, is the beginning of gender consciousness. When we contextualize it theoretically and try to change the customs, values and norms that legitimize violence against women, we become feminists. In the development of feminist theories, western women played greater role initially. But later on, women of color from Africa and Asia developed and further advanced feminist discourse. They brought their own experiences to feminist movement and the approach of inter-sectionality was also developed by them. Global challenge to sisterhood to white feminism was posed by the women of color. It is not right to call it an imported or foreign idea. We use economic theories of Marx, Keynes, Malthus and others - but no one call them imported. Ideas and ideologies are not the property of any specific nation or region. They travel, and become global when adopted by the people across the world.”

Confronting the opponents’ allegation that the feminist movement does not have any political base, the proponents of feminism strongly emphasize that it has found strong political base through feminist deliberations, discussions and articulations. As Afiya S. Zia writes in her book, ‘Faith and Feminism’ as “The absence of a political base for any movement would mean that such an enterprise becomes limited to an academic exercise” (Zia, 2018). She reiterates if there was no political substance in the feminist movement in Pakistan it would have been diminished long ago.

To feminists, feminism is the only social and political movement which has outgrown any political movement in terms of its evolution. Renowned women’s rights activist and author of several books Dr. Fouzia Saeed enunciated her views about feminist movement:

“Feminist movement in Pakistan is in continuous transformation. It is not made up of homogenous group of women, there are several initiatives taken up by rural, peasant women, urban working class women, polio workers, and LHWs etc. It should be understood in the preview of their history and their diverse social milieu.”

Young feminist organizers of the Aurat March are well aware of the dangers attached as well as expected that the slogans will attract accusations like “pushing western agenda, anti-Islamic, against the cultural values, exclusive and devoid of real issues” but they rejected all allegations completely. People who think that sexuality and body politics is foreign agenda are living in oblivion because these are very real issues and these are the issues of every woman.

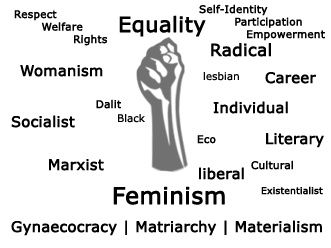

Aurat March is viewed by feminists as a vehicle for putting women’s question and feminism at the centre stage of political, parliamentary, social and journalistic discussions. It helped to bring the question of women’s oppression out of the drawing rooms and into the public place. The debate it generated at all levels is the biggest gain of the Aurat March. Moreover, it is inclusive in every way, as women from all walks of life participated, illiterate, urban, rural, working class, housewives, elitist, educated, young and old, artists, writers and thinkers were part of the March. It represented all ideologies of feminism, liberals, who demand personal liberties, welfare and legal provisions; radical feminism who want to break shackles of patriarchy and socialist feminism that stands for freedom from capitalism and patriarchy. The organizers are contesting that why asking for equal rights, ending gender-based violence, discrimination, and subjugation is asking too much?

Feminism in Pakistan has graduated to the next stage where it is taking up issues of public, private, state, society, home and family. The new generation’s feminist politics, ‘personal is political’ has come of age. During the 1980s, and even now - the focus of the state remained on women’s body - to cover it and to conceal it. “Chadar aur chardewari” (veil and four walls of the house) was glorified during the period of General Zia – simply to oppress women and imprison them within the confines of their homes.

4.6 Views of Religious Right: Conversation with Opponents of Feminism

Men and women from religious right viewed Aurat March from religious standpoint and termed it against religious and social values of Islamic republic of Pakistan. Founder of Alhuda, Dr. Farhat Hashmi who is based in Canada, when contacted through her organization- refused to participate in the research and her organization explained why they do not believe in feminism or activities related to Aurat March. In the following paragraph, her reply has been made part of the research;

“We have studied your questionnaire and we feel that Al-Huda International is an educational and welfare organization and do not have an expertise in responding to such matters. We as a nation are citizens of Islamic Republic of Pakistan and our actions as a nation should depict Islamic moral and values. Allah (s.w.t) has specified roles of men and women in the Quran and Prophet Muhammad (s.a.w) has explained and guided regarding every matter in detail. Actually, we need to implement the divine laws in our lives as individuals and collectively as a nation. A Muslim woman has been given a very dignified role in the society as a daughter, wife and mother and we need to study and implement it in our lives to be successful in this world and in the Hereafter.”

Most men and women from religious right interviewed for this research analysed feminism and recent Aurat March through religious framework. There was consensus among them that the slogans chanted by women in the March were vile, immodest and against Islamic and Pakistani cultural values. Only Council of Islamic Ideology (CII) chairman stressed that there is dire need to look behind these slogans, as to why Islamic and family values are at the verge of collapse. The chairman held a special meeting at CII to review emerging situation. His concern was as to why women brought issue of sexuality out in the public and how the family institution and social fabric could be preserved.

Religious right considers feminism a western propaganda, agenda or a conspiracy against values, traditions and Islamic beliefs because of its liberal and secular ideas about women’s rights, equality, oppression and subjugation. It is often termed as Bad or Hyper Feminism. The religious right including Islamic feminism (if any) uses religious framework and views women’s rights within the Islamic moral values which are derived from the source i.e. Quran and Sunnah. This section of society looks at feminism as foreign ideology, club of westernised elitist women, men haters and finds it alien and irrelevant and a threat to Islamic or Pakistani society.

Dr. Qibla Ayaz Chairman CII expressed his opinion about feminism in following words;

“Feminism in Pakistan is an elitist movement started by elitist women. The entire concept of feminist movement is misleading in the context of Pakistan due to the nature of the problems Pakistan faces. In Pakistan, women’s movement should start from subaltern women. From subaltern women, I mean the women from lower strata, poor, underprivileged and uneducated women. There is need to work on the emancipation of these women. They should be provided awareness about their rights. It is pertinent that their fathers and brothers should be sensitized to give them their due share in property rather than working directly with women only.”

The chairman of CII alleged that feminist movement in Pakistan has never tried to address issues of poor class women. He said;

“The feminist movement has never addressed issues of poor women. Elitist women belong to affluent families; all they want is to wear modern, western, expensive, revealing dresses. They want to move freely, with no barriers of social and religious traditions and to break free from all societal and religious values and traditions.”

However, he thought feminism could be relevant for Pakistan for the uplift of women from lower strata of Pakistan.

“Feminism is very relevant rather necessary for Pakistan. But feminism should carefully choose priorities and processes for dealing with problems that women face in Pakistani society. Elitist women’s have no real issues, only subaltern women in Pakistan have pressing issues and problems. Feminist movement in Pakistan has hardly done anything for subaltern women but the NGOs have done some good work in health and education.”

He added:

“We cannot follow the West completely, that is contradictory to our religious teachings and cultural values. What the west and feminists in Pakistan think is freedom for women is in fact their exploitation, pornography, dance and clubs, night clubs. There is no respect or freedom for women, men enjoy women’s sexuality and exploit them.”

Dr. Anis further elaborated:

“When we talk about feminism in the West, it has historical context and without knowing that context we cannot appreciate or disagree with the movement. The movement started in the state of affairs where for centuries Christianity and capitalism both tried their best not to allow women’s involvement and their proper role in the society. Unfortunately, Europe discarded Christianity, in the name of enlightenment, modernity and renaissance and reformation. We look at history from purely Eurocentric view point. When renaissance took place in Europe, we assumed that without renaissance no society can progress. There was rejection of religion as Natchez declared death of God of Christianity. Our intellectuals having heard or read about it assumed unless we become radical, follow west and challenge religion we cannot progress, same applies to feminism.”

Respondents from religious right countered liberal and secular feminism by arguing that feminism is not popular movement even in the western societies. It faced opposition from renowned sociologists and anthropologists who completely rejected the idea of feminism.

Dr. Anis responded

“Feminist movement did come out with some slogans but then anti feminism movements emerged in Europe and America and a number of renowned sociologists and anthropologists took position which totally rejected the concept of feminism. Since we have typical slavish mentality given to us by colonialism every single word which was said by British or American authors become word of bible for us. We use same jargons, those who use jargons are considered modern while the rest are considered conservative and backward.”

He reiterated that feminism is relevant to westerns societies but not societies like ours.

“I believe that in societies which have gone through the model of European society, emergence of feminism was a natural phenomenon. Societies where that cultural, epistemic, historical background does not exist, for them it is something that is external and which cannot gel with the culture and society. Unfortunately, it’s not only your topic, but most of the young M.S. or Ph.D. scholars come up with findings studied, analyzed and concluded in a paradigm which is very suitable for an empiricist environment, where empirical reality is the only reality; there is no room for any ethical moral, cultural values.”

Dr. Anis emphasised that social issues are non-binary issues; Islam addresses society as a whole.

“We don’t divide people into men and women. Feminists are obsessed with gender slogans, while male chauvinists are obsessed with male superiority. In my view, both are wrong. I believe that Islamic culture and faith does not allow such kind of movement because Islamic justice is not simply for women or men. It is for the whole humanity and therefore the Quran never uses gender loaded jargons but always talks about kindness, compassion, love, understanding, rationality and taking care of obligations. Therefore, different paradigms are needed address issues of different cultures.”

There was consensus among the research participants from religious right that feminism is an implant and a foreign idea. Many vocal opponents of feminism and Aurat March, declined to be part of the research after knowing the topic of research though agreed when contacted initially.

Pakistani society is even more polarized today than ever before and is confronted with infinite divisionism on the basis of religion, ethnicity, class, caste and gender. The views shared by the research participants about every issue explored during this research mostly were conflicting and contrary to each other. There was not a single issue on which the two groups agreed. Going beyond binaries was impossible because binaries always existed and still exist in our society. However the powerful majoritarian group i.e. religious right, is positioned higher on the social hierarchy reiterated that their standpoint is superior because they use Islamic ethical paradigm. However the second group which is situated lower on the social hierarchy has strong realization of their subjugation and discrimination continuously struggling to improve their situation, working towards balancing power relations in the unequal social structures. This research project remained controversial for powerful group throughout the interviews, many of the potential interviewees declined to be part of this research after fully grasping the topic of the research, though they had initially agreed to participate in the interviews. However, those who accepted to participate in the interviews insisted that their standpoint is superior because it is based on Islamic ethical paradigm.

Both groups’ views about feminism were contrary to each other and not a single point of consensus was achieved. In conclusion, there is no possibility of convergence between the religious right and feminist groups. Seemingly this divergence will persist because both use different paradigms to explain issues regarding women rights, equality and emancipation.

4.7 Contemporary Feminism Around the World

Feminism in the region and at global levels is discussing wide range of issues starting from economic and political empowerment to equal universal human rights, freedom from patriarchy to prostitution, birth control, sexual violence, pornography, AIDS, heterosexuality and lesbianism to climate change and environment and anti-capitalist alternative to neoliberal feminism. As far as sexuality/ body politics is concerned, it has long been a major issue within Women’s Studies, feminist theory and politics. Contemporary feminism is asking ‘What is the relationship between sexuality and gender inequality? In her book Sexuality and Feminism, Diane Richardson connects how sexuality and women’s subjugation are interrelated. For many radical feminists, sexuality is at the heart of male domination; it is seen as a key mechanism of patriarchal control (Rawland and Klein, 1996). Indeed, some writers have argued that it is the primary means by which men exercise and maintain power and control over women. Catharine MacKinnon’s work, for example, has been significant in the development of such analysis. “Central to most radical feminist accounts is the view that sexuality, as it is currently constructed, is not simply a reflection of the power that men have over women in other spheres, but is also productive of those unequal power relationships. In other words, sexual relations both reflect and serve to maintain women’s subordination. From this perspective, the concern is not so much how women’s sex lives are affected by gender inequalities but, more generally, how patriarchal constructions of sexuality constrain women in many aspects of their lives. For instance, it is becoming clearer how sexuality affects women’s position in the labor market in numerous ways; from being judged by their looks as right (or wrong) for the job, to sexual harassment in the work place as a common reason for leaving employment” (Richardson, 1997).

Forty years ago American women launched a liberation movement for freedom and equality. They achieved a revolution in the Western world and created a vision for women and girls everywhere. Today, women’s economic and social participation is considered a standard requirement for a nation’s healthy democratic development (Chesler and Hughes, 2004). Both authors concluded in their article that major issues of feminism in 21st century are: Sexism, division of domestic labor, media, glass ceiling, social inequality and violence against women. If we look at the issues taken up by 3rd generation of feminism in Pakistan, they are in accordance with their global counterparts. The body politics which was started by the second wave of feminism in the United States and made great headways globally, has finally reached Pakistan. Khan (2019) in her interview says, “Women are operating with a very thin wedge, and they are placing that wedge where they think they can make some gains in an increasingly restricted civil society, but with some openings for democratic governance. So it’s not even done as part of a prepared, coherent strategy, it’s just that naturally you go for where you think there’s some room to manoeuvre.”

The achievements of feminism in the United States and Europe are phenomenal and perhaps incomparable to their counterparts in Asia and in South Asia. In South Asian context, unfortunately women’s rights are believed to be embedded in the South Asian cultures and values, women’s individual rights are seen in relation to men and hence subjugated in favor of men or community. In addition, the equal rights of women are perceived as secular ideology by the states and society in general. South Asian states and Pakistan in particular, are strongly governed by religious traditions; their perception about secularism equals atheism. However, when it comes to empowerment of women in South Asia, it is overtly focused on poverty alleviation, welfare and basic needs instead of focusing on realization of individual rights of women as equal citizens.

In Pakistan, women are protected by law but in practice, the implementation of these laws is systematically hindered because of deeply entrenched socio- cultural-economic barriers and prejudices against women. Women in Pakistan generally have lower status as compared to men due to valuation of genders by the society. Their status and their ability to exercise their socio- economic and political rights vary across class, religion, education, urban, rural locations and ethnicity. Moreover masculinization and militarization of the society had intertwined relationship; it creates unequal power relations and hence forces them to stay in the four walls of the house which exacerbates violence of all kinds and assign them subservient roles. Overall, South Asian countries have egocentric cultures in which men are perceived superior to women and women remain subservient to them feminism or women’s movements in these countries have long way to reach to the extent of liberation and empowerment achieved by women in the United States and Europe.

5 . CONCLUSIONS