2 . REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

2.1 Male-Female Interactions in the Classroom Setting

Research on learner-learner or peer-interaction in the classroom context has been reported to be replete with males’ dominance. Such gender inequality in the educational patterns of the classroom settings are often said to be in favor of males (Gass and Varonis, 1986; Coates, 1986; Holmes, 1992, 1994; Sunderland, 1992, 1994; Mills, 1995). Esposito’s (1979) research seems to support this contention arguing that boys, in mixed-sex conversations are observed to maintain their dominance through their tendency to interrupt their female classmates far more frequently than the other way around. For example, Gass and Varonis’ (1986) research study among Japanese male and female students learning English as a second language in the United States of America has revealed that men employ more conversational opportunities to take more turns and to dominate nearly all classroom interactions. Men, in this connection, have been reported to be superior to females either in stating opinions or in debating.

These gender differences and inequalities are, according to Coates (1986) and Holmes (1992, 1994), culturally and socially originated. Such sex biased conversational practices where males have been shown to dominate the classroom space of the educational setting “may reflect that men tended to take the leadership role more often than women” (Holmes, 1994: 160). Coates (1986) contends in this regard that this conversational dominance among males to compete more regularly for the floor, to take longer turns and interrupt more frequently may reflect the contrasting social roles of the sex groups in patriarchal societies. Such discursive practices employed by males to maintain their superiority over the other sex.

Almost the same patterns of results have been echoed in Munro’s (1987) study. The findings of this investigation have indicated that male students tend to adopt more disruptive conversational strategies. They have been observed to participate far more often either through their amount of talk, or through their frequent interruptions.

Revisiting Munro’s (1987) recorded tapes of small group interactions among learners of English in Sydney, Holmes (1994) found more biased conversational practices. Male students seem to interrupt more often and are far more likely to take more conversational turns than females. In her focus on the analysis of data drawn from ESL classrooms in Australia and Newzealand, Holmes (1989) points out that male students volunteer far more often as a response to their teachers’ questions. They also seem to issue more questions, which may surely expand and enhance their question-related language functions.

Such a finding can clearly be explained in terms of Munro’s (1987) contention that societal attitudes and the early socialization of girls and boys may create biased cultural expectations. As a matter of fact, ‘girls are supposed to be dependent, passive, non-competitive; boys are said to be assertive, independent, unsentimental and courageous’ (Munro, 1987: 1). This tendency among male students to interrupt the classroom discussion is reported to engender an imbalance of conversational routines as “the interrupters prevent the speakers from finishing their turn, at the same time gaining a turn for themselves” (Coates, 1986: 94).

Sunderland (1994) observes in this regard that gender inequalities, as is the common feature of most societies, are unfortunately reproduced and reinforced in the classroom settings. Male participants are more liable to exercise their dominance of conversational models through the use of more questions and more interruptions. This may surely be conducive to the predominance of male voices and the invisibility or submergence of their female classmates. This interruptiveness, according to Tannen (1994), has been deployed as a more powerful and dominant “device for expressing power and control in conversations” (p.56).

This asymmetry characterizing the conversational discourses of both male and female students is in fact a serious educational concern. This imbalance in turn-taking may preclude and plague the potential of girls in any classroom activity, and by implication may curtail their motivation to learn. We made to align with Holmes’ (1994) forceful argument that “women are getting less than their fair share of opportunities to practice using the language” (Holmes, 1994: 157). The turn-taking rules of conversation are utterly distorted to male students’ favor.

2.2 Teachers’ Biased Practices

With respect to the differential treatment of girls and boys, there is strong evidence displaying the fact that female learners tend to get less attention from teachers, not only in quantity but also in the quality of feedback they receive.

To discern how gender bias practices reproduced in the classroom, and how the patriarchal values and attitudes are brought into it, classroom interaction has been one of many potential processes whereby male students enforced their dominance over females. “Male students in mixed-class”, Sunderland (1994) comments, “tend to demand the lion’s share of the teachers’ attention and get it, in terms of quantity and quality” (Sunderland, 1994: 187). With this line of reasoning in mind, it has also been argued that sex inequalities in the distribution of sex roles in societies are also transferred and perpetuated in the classroom context through the teachers’ differential amount of attention, praise and criticism geared towards the two sex groups (Coates, 1986; Mills, 1995; Holmes, 1994; Sunderland, 1994; Mouaid, 2013; Khoumich and Benattabou, 2020).

The literature on the differential teacher treatment based on gender tends to favor boys over girls. Girls are reported to get less of the teacher’s amount of attention, and less praise than boys. Teachers are also observed to interact more often with male students than with females. This gender imbalance characterizing the classroom talk has been epitomized in Kelly’s (1988) most intriguing but gloomy contention that:

‘On average teachers spend 44 percent of their time with girls, and 56 percent of their time with boys. But if this is worked out over the length of a child’s school career, say 15000 hours, it means that 1800 more hours have been spent with boys than with girls’ (Kelly, 1988:13).

Such an unfair differential treatment has also been documented in another study reporting that boys turn out to dominate classroom interaction with teachers, thereby issuing more contributions and getting more feedback from their teachers than do their corresponding female peers (Spender, 1980; Coates, 1986; Sunderland, 1994; Holmes, 1994). Spender (1980), in particular, reports that two-thirds of the teacher’s feedback is allotted to boys, while girls get only the remained third. This is a serious problem, which may have the potential to curtail female language learners’ aspiration and enthusiasm to seek more opportunities to interact with their peers in the classroom.

This uneven distribution of the teacher’s attention in the classroom discourse is outlined in Mills’ (1995) account of the literature arguing that girls are denied the right of any teacher’s feedback. This leaves the floor for boys to adopt various discourse practices to draw the teacher’s eye contact with them, and to dominate most turn-takings (Mills, 1995: 136).

If this is truly the case, therefore, then the most pressing educational concern for most specialists in the field would be to seek the optimum ways in which such lopsidedness in education should be eradicated. The corollary of this is that there is a fear that female learners may refrain from any classroom participation, an essential component contributing to success in any language learning process.

Educational institutions have oftentimes been criticized for being inherently sexist as they are, wittingly or not, reproducing and perpetuating at the same time the sex-biased values and norms of their corresponding societies. Teachers are no exception because they are reported to display more gender disparities through their interaction with male and female students, and through the amount of attention and feedback they unevenly allot to them.

More intriguing and revealing perhaps is study of Dweck et al. (1978) which shows a kind of imbalanced paradox in terms of the teacher’s amount of praise and criticism of the two sex groups. Boys are reported to receive higher proportion of criticism because of their behavior ‘calling out and interrupting’, and are praised for their academic performance. Surprisingly enough, girls are found to receive more criticism from the teacher because of their low academic achievement, but more praise for their good behavior and ‘quietness’ (cited in Kelly, 1988: 15).

The study of classroom interaction, particularly teacher-learner interaction, has continued to bring about more interesting and important research results. Sadker and Sadker (1994) report, in this regard, more biased practices favoring male students. Good and Brophy (1990) confirm the same finding delineating the fact that boys are given more opportunities to enhance their ideas, and they are far more likely to receive more attention than their female classmates.

Video recordings of gender practices in the classroom context display the same patterns of results. Swann and Graddol (1988) have observed through their video recordings that the teachers’ gazes have been distributed unequally to both male and female students. Male students are noticed to receive a large share of the teachers’ instructions, criticism, praise and gazes. Eye gazes have been disproportionately employed to encourage boys than girls.

Another evidence in support of the view that male learners tend to enjoy more attention and more constructive feedback from teachers than females emanates from the Moroccan context. In her study of male and female EFL students in Morocco, Mouaid (2013) noted that, though instructors do not demonstrate any deliberate victimization of young men or young women, their attention was found to be more oriented towards boys than girls either when presenting their input and/or when issuing some comments on students’ learning practices. What is more, when checking the measure of time allotted to each sex, male students were observed to receive more time than females.

Such a pattern of results seems to work against female students’ progress in language learning as they may feel being marginalized or excluded altogether not receiving any feedback on their contributions (Liu, 2006). This may surely prevent female students from performing their due share in foreign language classes.

If Spender’s (1982) view that it is virtually impossible to divide a teacher’s attention equally among girls and boys is tenable, then one is safely led to argue that classroom talk is incessantly found to be discriminating against girls and not the other way around. Female students continue to be deprived of self-expression, and remain almost unheard forced, intentionally or not, into complete silence (Holmes, 1994; Mills, 1995).

This asymmetrical treatment of male and female students may also be attributed to the teacher’s sex as a potential determinant factor. Evidence from research, however, seems to refute such an assumption. Sunderland (1994) contends in this regard that “the sex of the teacher makes less difference to the way she or he behaves than the sex of her or his students” (Sunderland, 1994: 148). Nevertheless, research overlooked the fact that the sex of a teacher can affect his\her choice of the gendered material to be taught, the topics discussed in class, and the gendered tests students are supposed to be evaluated in.

One is reasonably led to observe that if boys dominate the classroom context through their tendency to take more turns, and to interrupt the classroom discussion far more often, this may surely put them at a greater advantage than their female peers. More troublesome perhaps is that there is more evidence from research indicating that teachers, be they males or females, are far more likely observed to perpetuate this biased practice through encouraging boys far more often giving them more eye-attention and more feedback.

These different behavioral conducts may have the evils of blatant unfairness towards female learners. This is a more challenging problem that must be the concern of all practitioners as female students may be at higher stakes of being indoctrinated to believe that their academic performance is far much lesser than their male counterpart, and this is in no way compatible with their teachers’ expectations (Holmes, 1989). Other forms of classroom behavior such as ‘calling out’ or ‘interrupting’ are more accepted from boys than from girls (Sunderland, 1994).

If prior research indicates that there is a tendency among male students to dominate the classroom talk, particularly in mixed-sex classes, then this might perhaps be a reflection of the prevailing biased attitudes of patriarchal societies, which may induce teachers, irrespective of their sex, to internalize their gender-biased ideologies according to which they will treat male and female students. There is a tacit assumption here that if teachers continue to give more resources to boys than to girls, it would come up as no surprise that boys will undoubtedly show more educational gains.

On a somewhat similar note, Holmes (1995) reports that if such gender inequities continue to favor boys giving them more chances to answer the teachers’ questions, and receive more positive reward on their contributions, then girls are more liable to be educationally disadvantaged. It follows from this that sex inequalities in the classroom where teachers may distribute unequal proportions of attention, praise and criticism may do more harm than good to female students’ self-image, their motivation to work and collaborate, and their aspirations to excel in the classroom.

By the same token, there is a fear that girls may get the false impression that the classroom context is a male-dominated space par excellence. Boys, on the other hand, are placed in an optimum setting where they are very much likely to make use of their full potential to the detriment of their female peers.

What should have emerged from above is that gender inequalities prevalent in societies are unavoidably reproduced and strengthened in the classroom context (Sunderland, 1994; Holmes, 1994; Mills, 1995). The fact that girls are discriminated against in terms of boys’ dominance of the physical as well as the verbal space of the classroom (Brouwer, 1987), and in terms of the teachers’ uneven amount of attention may put them at higher stakes of being unfairly excluded from almost all classroom conversational interactions.

2.3 Males and Females’ Preferred Themes and Topics

Discrimination against women and schoolgirls in particular seems to persist at almost all aspects of education. Benattabou (2021) stressed that “social and cultural misconceptions […] continue to consider them [women] as inferior, subordinate, submissive and perpetually in dire need of man’s control” (Benattabou, 2021: 18). This control is extended to the choice of topics to be taught at school and the activities through which learning takes place. There is evidence that preference of some topics over others is not inherited but rather enhanced by the school’s attitudes and expectations which concord with the stereotypical views of all stakeholders (OECD, 2015 mentioned in Munro, 1987).

In a most recent study, students’ interest in a reading material was found to be significantly related to their gender, to the topic and to the genre of the text (Lepper et al., 2021). The researchers concluded that “text-based interest represents an important reason for intrinsically motivated reading, which, in turn, is a key competence and crucial prerequisite for academic success and participation in society” (p. 10). Other studies stressed the differences that exist between males and females regarding their preferences of narrative text genres or informational ones (Clark and Foster, 2005; Clark, 2019).

Even at the tertiary level, where students are supposed to develop a sense of autonomy, research revealed that interest in a reading material significantly correlates with the kind of topic a text revolves around. Students, in this sense, decide to finish the whole text or just ignore it immediately after reading the title (Flowerday and Shell, 2015). In The United Kingdom, for instance, Clark and Foster (2005) reported that, unlike girls, boys appeared to be less interested in reading love stories, texts about relationships, or texts about pets. Girls, by contrast, did not appreciate war, crime, science fiction, and sports topics.

Teachers are reported to constantly make use of texts and topics, which tend to disseminate and perpetuate certain biased stereotypes like the father is a newspaper reader and the mother is a full-time cook in the kitchen. Doctors usually portrayed as males and nurses as females. Boys are playing football while girls are playing with their dolls designing their clothes and putting on makeup. These kinds of gendered roles seem to persist even after leaving school and they tend to affect the girls’ self-esteem and make them believe that the best they can achieve is being a housewife, a primary school teacher, or a nurse. Therefore, all teaching materials should be questioned before they are put into practice to see if they are gender bias-free. The UNESCO’s (2015) annual guide for gender equality in teacher education policy and practices recommends that the ministry of education in any country should ‘revise’ the curriculum to make sure that it clearly guarantees gender equality and should eliminate any content which seems to favor one gender over another (p.61).

A significant body of research emphasized the need to be gender-sensitive in teaching practices particularly with respect to the choice of the content and material that should be appealing to the interest of both sex groups. Zuga (1999), for example, reports about instances of teaching materials which persistently involve topics that girls, in specific, do not possess any background knowledge about. The findings of this study indicate that female learners are found to have no physical science experience, either in the use of batteries, electric toys, or pulleys. Such a tendency seems to put them at a greater disadvantage while learning physics terminology and systems. Jones et al. (2000) cogently reported in this regard that “boys more than girls wanted to learn about planes, cars, computers, light, electricity, radioactivity, new sources of energy, and x-rays. More girls than boys wanted to learn about rainbows, healthy eating, colors, animal communication, and AIDS” (p. 185).

The content of Moroccan EFL textbooks has been found to be replete with more topics which seem to be more appealing to boys than girls. Masculine themes like football, body weight and wrestling tend to pervade the content of a whole unit of these textbooks or are presented as topics in the end-of-year national exams. In the Catch-up national exam of English for the science stream of the year of 2013, for example, the title of the text was “A football legend” accompanied with a picture of Leonel Messi (Golden Ball winner). In the writing section, students were again asked to write a report about the sand marathon. You can imagine how easy it would be for almost all boys to reiterate the tons of information they informally learned from media about the story of Messi; and how difficult it was for girls who do not consider football as something interesting to watch or read about. Unlike boys, girls in this situation are forced to adopt a bottom-up reading approach where they have to decode small parts of a text to reach a whole understanding, a process that can take a long time and whose purpose is not necessarily achieved.

More interesting perhaps in this regard is Ebrahimi and Javanbakht’s (2015) research study which was of an experimental design and whose conclusion emphasized that being interested in a topic positively impacts reading comprehension. When topics are attractive to students, reading becomes easier and students are able to guess meaning from the context. The findings of their study tend to corroborate a body of research (Eidswick, 2010; Lee, 2009; Schraw et al., 1995) which proved that topic interest can make a reader pay careful attention to comprehend the material. Interest was categorized in two dimensions both individual and situational; the former is a prior and permanent state while the latter is temporary created by an emerging situation such as a reading text or test (Alexander and Jetton, 2000). What follows from the aforementioned studies is that ‘interest’ in all its facets is vital in fostering students’ understanding and retaining of information.

Since students tend to spend most of their time at school with their teachers getting influenced by their behavior, their beliefs, and gendered topics, an instructor is recommended to present a positive and a biased-free model for students. In this respect, research revealed that teachers can adapt teaching styles and methods which are appealing to both sex groups. They can reach that through finding a significant link with all students’ prior knowledge and what they really know about the world. For instance, there is no point in teaching students, who live in the middle of a jungle, about the train and they have never seen one. In this sense, female students tend to complain that the content of the course they are usually presented with has nothing to do with their everyday life (Markert, 2003). It is recommended for teachers, therefore, to conduct interest analysis whose findings can be utilized to build a solid course content that appeals to both genders and is related to their experiences (Wills, 2001).

There is a call in all previous research for teachers to reconsider their teaching materials and teaching practices. For example, instead of trying to create a competitive atmosphere, a teacher should encourage all students to work collaboratively in teams. Teachers are also advised to provide examples and draw demonstrations which both males and females can identify with (Markert, 2003; Wills, 2001). Weber (2004), in a research about gender-based preferences, showed that there are significant differences between boys and girls in the topics and activities they find interesting. The researcher stressed that girls preferred topics that stimulated communication and socialization whereas boys were more interested in technology and how things are constructed. Females can also be interested in technology topics provided that they relate to interactive and social contexts.

On a similar note, some researchers suggested having single-sex classes where female students enjoy more support and more interaction with their teachers. Lee (1998) claimed that girls in same-sex schools achieved distinctively well in subjects that are considered masculine (Math, sciences, and technology). They were observed to be interested in the learning content and they were intrinsically motivated to achieve. Moreover, they were not driven by society’s cultural beliefs in deciding a future career. Instead, girls in single-sex classes appeared to be less submissive and more challenging to the idea of male occupations. Their concern was much more pragmatic, and they preferred highly paid jobs (Helwig, 1998).

On the ground of what has been discussed so far in this review of the literature one may contend that evidence from studies on learner-learner interaction, teacher-learner differential treatment, and teachers bias in their choice and use of some teaching materials seems to exude and carry one single message that the education of female students is indeed at a great disadvantage as they are both socially and conversationally marginalized and excluded altogether in the classroom settings.

Gender bias seems to permeate almost all teaching and learning practices either in terms of male-female students’ unequal interactions, teachers’ biased treatments of these students, and/or in their asymmetrical choice of teaching materials their students are exposed to (Sunderland, 1994).

4 . RESULTS

4.1 Males and Females’ Differences in Talking Time Opportunities

As the t-test output depicts, males (N = 45) perceive the talking time granted to them in a more positive way M = 10.0667 (SD = 1.15470). By comparison, females (N = 49) seem to be less satisfied with the time opportunities they are offered, M = 9.7143 (SD = .80904).

To test the hypothesis that there is a statistically significant difference between males and females in students talking time, an independent sample t-test is used. However, to obtain valid results, we need to make sure that males’ and females’ distributions are sufficiently and normally distributed and meet the assumptions of performing an independent samples t-test (Table 1).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics associated with gender differences in the talking time

|

Gender

|

N

|

Mean

|

Std. Deviation

|

Std. Error Mean

|

|

Boys

|

45

|

10.0667

|

1.15470

|

0.16496

|

|

Girls

|

49

|

9.7143

|

0.80904

|

0.12060

|

In table 2, the calculated Skewness z-value is .130, and the Kurtosis z-value is -1.027. So, both z-values are within +/- 1.96. We can conclude that our data sample is slightly skewed and kurtotic, but it does not differ significantly from normality. We can say that our data is approximately normally distributed in terms of Skewness and Kurtosis.

Table 2. Skewness and Kurtosis of male and female participants

|

N

|

Mean

|

Skewness

|

Std. Error

|

Kurtosis

|

Std. Error

|

|

94

|

1.47

|

0.130

|

0.249

|

-1.027

|

0.493

|

The homogeneity of variance assumption (Table 3) is satisfied via Levene’s test (p = .008). The independent samples t-test is associated with a statistically significant result t = -1.724, p = .088. Thus, males are statistically and significantly satisfied with the time they are granted. Therefore, the null hypothesis assuming that there is no significant difference between males and females in talking time opportunities is rejected, and the alternative hypothesis stating that there is a significant difference between males and females in students talking time is reinforced in such a way that girls are at a disadvantage with respect to students talking time opportunities.

Table 3. Differences between males and females in the talking time granted for each one of them

|

|

Levene’s test for equality of variances

|

t-test for equality of means

|

95% CID

|

|

|

F

|

Sig.

|

T

|

Df

|

Sig.(2-T)

|

MD

|

Std. ED

|

Lower

|

Upper

|

|

EVA

|

7.333

|

0.008

|

-1.699

|

92

|

0.093

|

-0.35238

|

0.20737

|

-0.76423

|

0.05947

|

|

EVNA

|

|

|

-1.724

|

86.171

|

0.088

|

-0.35238

|

0.20434

|

-0.75859

|

0.05383

|

The assumption that girls are at a disadvantage in terms of the talking time they are granted is also analyzed using frequencies. The table 4 demonstrates the students’ views on who talks more in class. The findings show that boys speak three times more than girls. They are predominating the class talk with a share of 76.6 % against only 23.4% for girls. They tend to take the floor far more often and for much more time than do their female peers.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics associated with students' views on who talks more in class

|

Gender

|

Frequency

|

Percent

|

Valid Percent

|

Cumulative Percent

|

|

Boys

|

72

|

76.6

|

76.6

|

76.6

|

|

Girls

|

22

|

23.4

|

23.4

|

100.0

|

|

Total

|

94

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

|

Although there is more evidence from research reporting female’s superiority over males regarding their language achievement tests (Riding and Banner, 1986; Halpern, 1992; Sunderland, 2010; Murphy, 2010; Główka, 2014; Benattabou et al., 2021), one would wonder why there is this predominance among boys as opposed to girls with respect to their classroom talking time. The answer is probably suggested by the findings reported in table 5, which states that girls are constantly interrupted by boys. The results demonstrate that boys interrupt girls very often. Students think that boys hinder girls from finishing their talk with a proportion of 64.9% against only 35.1% who stated that it is girls who often interrupt boys.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics associated with students’ view on who often interrupts others

|

Gender

|

Frequency

|

Percent

|

Valid Percent

|

Cumulative Percent

|

|

Boys

|

61

|

64.9

|

64.9

|

64.9

|

|

Girls

|

33

|

35.1

|

35.1

|

100.0

|

|

Total

|

94

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

|

4.2 Differences in Males’ and Females’ Perceptions of Teacher Practices and Teaching Pedagogy

The findings in the table 6 show that males (N = 45) tend to perceive their teachers practices in a more positive way M = 27.8000 (SD = 4.90176). In contrast, females (N = 49) do not appreciate much the teacher’s practices and the teacher’s teaching pedagogy, M= 26.5714 (SD = 5.36579).

Table 6. Descriptive statistics associated with female and male perceptions of teacher practices

|

Gender

|

N

|

Mean

|

Std. deviation

|

Std. error mean

|

|

Male

|

45

|

27.8000

|

4.90176

|

.73067

|

|

Female

|

49

|

26.5714

|

5.36579

|

.76654

|

To test the hypothesis that teacher practices are biased in favor of males, an independent sample t-test is used. The independent samples t-test is associated with a statistically significant result of t = -1.160, df = 92, p = .024. Therefore, the P-value is less than 05%, and thus the alternative hypothesis stating that there is a significant difference between males and females in perceiving their teacher-biased practices should be accepted in such a way that girls are again unequally treated in classes.

Table 7. Differences between males’ and females’ perceptions of teaching practices

|

|

Levene's test for equality of variances

|

t-test for equality of means

|

95% CID

|

|

|

F

|

Sig.

|

T

|

Df

|

Sig. (2-T)

|

MD

|

Std. ED

|

Lower

|

Upper

|

|

EVA

|

0.001

|

0.073

|

-1.156

|

92

|

0.025

|

-1.22857

|

1.06314

|

-3.34005

|

.88291

|

|

EVNA

|

|

|

-1.160

|

91.998

|

0.024

|

-1.22857

|

1.05902

|

-3.33188

|

.87474

|

4.3 Differences between Males’ and Females’ Preferences Regarding the Classroom Themes and Topics

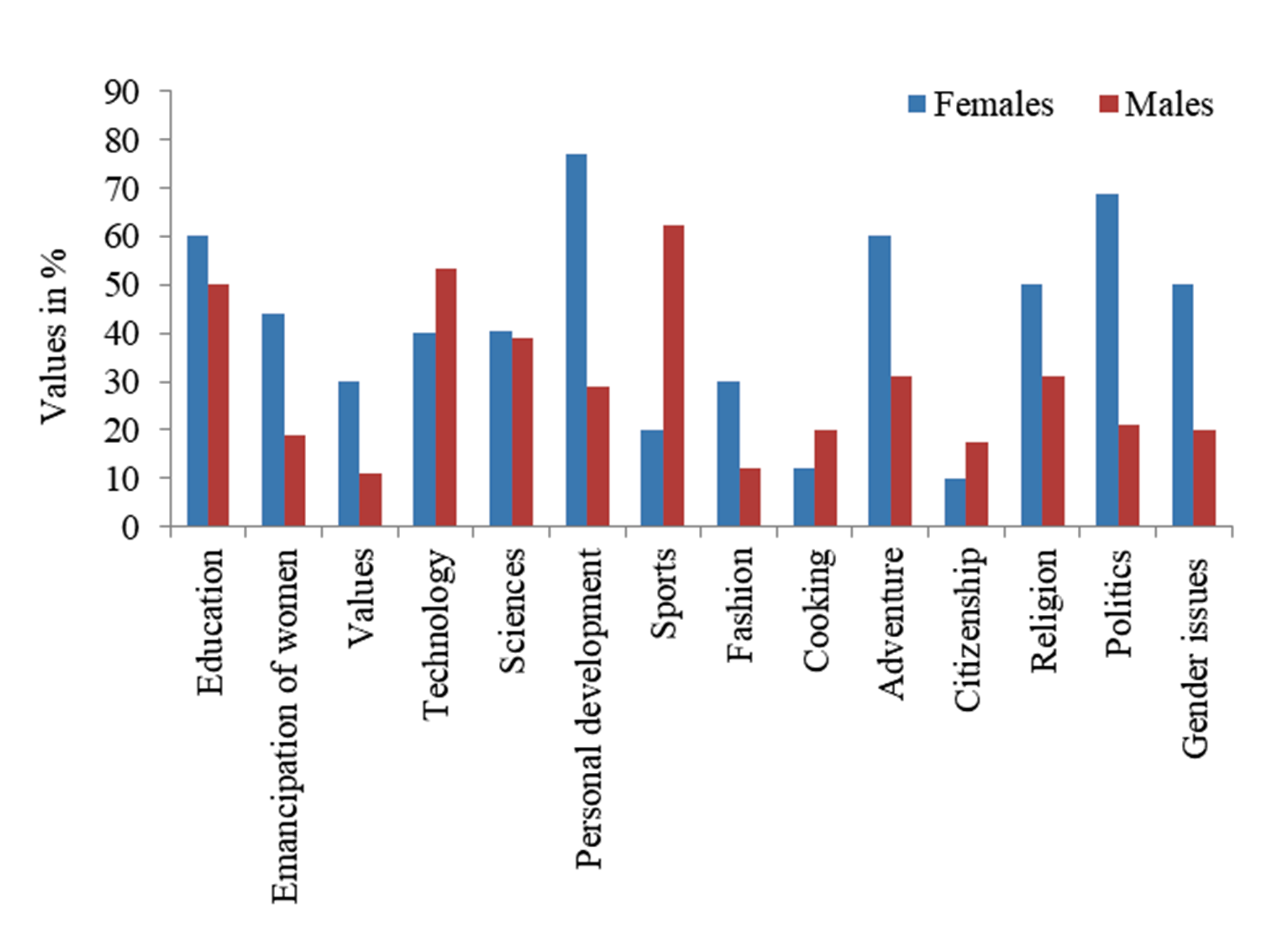

Students were given a ‘tick all that apply’ kind of question to express their preferences vis-à-vis 14 suggested topics. The data have been analyzed to determine the distribution of boys and girls through the chosen themes. As may be depicted in figure 1, there are apparent differences in the frequency distribution of boys’ and girls’ topic preferences.

Concerning the overall frequencies of the chosen themes among the 14 suggested topics, personal development stands out to be the most appreciated topic by female students (76.67%). Surprisingly, politics came second and was chosen by females with a percentage of 68.89%. The third position was split between religion and gender issues with a share of 50% for each. Males mostly choose sports with a portion of 62.17% and technology with a share of 53.48%. The least represented theme was citizenship for both males and females with a proportion of 17.39% and 11.11%, respectively.

This quantitative analysis indicates that female students preferred topics are far from what is actually taught. Girls have a tendency to opt for such themes as personal development, politics, and adventure. It is very disappointing that such themes, which girls prefer most, do not figure in the Moroccan EFL textbooks. Girls also stressed their need for a ‘gender education’ or themes about gender issues to be learned and discussed in class (50%). Such a finding is consonant with Gurian’s (2011) contention reported in his book: ‘Boys and Girls learn differently: A guide for teachers and parents’, stating that “adults are just now learning [that gender issues] can be taught to boys and girls’ [and that] this kind of teaching, […] is targeted to both boys and girls and exists specifically to help teachers and students facilitate dialogue between young males and females” (Gurian, 2011: 294).

5 . DISCUSSION, IMPLICATIONS, AND LIMITATIONS

There is gender bias in teachers’ practices which may not appeal to either males or females is both informative and highly instructive. First, the teaching pedagogy and the activities presented in class seem to be more interesting to males, while girls appear to struggle for appropriate assimilation of the content already designed by males (Benattabou, 2021). Previous studies indicated that socially relevant topics were more appealing to girls, whereas boys were more concerned with the ‘know how’ (Shroyer et al., 1995). In addition to that, these authors concluded that topics related to the environment, people, and the application of this knowledge to social conditions was more associated with girls than boys.

Research has also discovered that there are teaching strategies and teaching styles that can be described as particularly gender biased (Brunner and Bennett, 1997 among others). Females, for instance, are more inclined toward coordinated effort over rivalry (Chapman, 2000), which is consistent with contemporary teaching approaches whereby the notable utilization of individual tasks is shifting toward group work. Moreover, educational materials might be associated in significant manners with certain students’ prior knowledge about the world and not others (Zuga, 1999). Accordingly, female students, in particular, frequently think that the themes and topics they are presented with in class tend to be most of the time irrelevant to their experiences in life.

It is actually unjust, and the stakes may unavoidably be very high if ever we continue to overlook the prevalence of these masculine themes in the content presented in class. Female learners’ chances to enter new occupational spheres traditionally reserved for men will be very low. This finds expression in Maggie Sokolik’s argument that “girls who read about only male pilots are much less likely to indicate they are interested in flying than girls who read about both male and female pilots” (Quoted in Stanley, 2001: 4).

Another danger may arise from the assumption that if female students are not given equal distributions regarding classroom talking-time, this may perhaps be a blessing rehearsal for their male peers by extending for them more opportunities for classroom practice, but a curse for females who may surely have fewer access to enhance their language performance (Sunderland, 1992, 1994; Byrnes, 1994).

This is indeed a strong plea for concern because research has incessantly reported that gender inequalities, which shape the content and the practices of the classroom context may have the potential to place female language learners at a great disadvantage and by implication may hinder their language learning proficiency. In so doing, it is also possible that female language learners may develop a sense of low self-esteem, a prerequisite condition for better attainments in language learning.

When it comes to teachers, they “should use examples with which both genders can identify” (Weber and Custer, 2005: 56). Theme preference was the subsequent significant focal point of this investigation which helped in detecting examples of topics that are beyond the traditional ones. This is significant since there are inherited interests in themes that certainly contrast with gender-specific preferences. Otherwise, perfectly planned activities can conceivably involve students in topics that might be of minimal interest.

In the current research, the themes evaluated as most intriguing were analyzed by sex. A striking level of difference was found in four of the fourteen proposed themes getting higher evaluations by girls. The marks of distinction are reliable with the significant differences found in this investigation, with females showing high interest in personal development, politics, adventure, and education (Figure 1). This may have significant ramifications for gender-balanced choice of topics in language teaching.

It is, therefore, the responsibility of the textbook writers to rethink the content of the existing textbooks and design it in such a way that it should meet the needs and preferences of both sex groups. Educational program designers, therefore, should learn from research in gender studies if they have the intention to fathom how girls learn, and what their needs and preferences are, and based on that information, they may be in a better position to look for the most propitious ways of how to heighten their motivation to learn and make an informed progress. Topics like personal development, politics, and gender issues may be more appealing to girls than science and technology. Instructors should choose and create exercises that will convey and build up content that is appealing to both girls and boys. As a matter of fact, investigating students’ preferences in this study will represent a database for syllabus designers and teachers alike to know which territories to stand on while choosing and creating language content for the instruction of both girls and boys.

Surprisingly enough, both girls and boys were found to be the least interested in themes related to ‘ethical and societal values’, a reality that may reveal a total lack of responsibility towards national and social issues. This result is somehow threatening our national security. It is the duty of all stakeholders pertaining to the educational sector to design informed strategies to sensitize students of both sexes about such core human values as ethics, citizenship, acceptance of the other/ tolerance, and the love of one’s nation/ patriotism.

Our research cannot be without limitations. Thus, this examination is restricted in the sense that it included just second year students from three classes. It would be more interesting if comparable examinations conducted with other levels and across different age categories. On the grounds, the students in this population were from low to middle socioeconomic backgrounds, future studies ought to consider gender bias in schools across different socioeconomic levels and across urban and rural contexts.

,

Abderrahim Khoumich 2

,

Abderrahim Khoumich 2

,

Mounir Kanoubi 3

,

Mounir Kanoubi 3